THE LM ON ITS OWN

The fifth day of the Apollo 9 mission was the crucial test for the LM. Schweickart and McDivitt entered the LM, powered it up, and prepared to separate from the command module. They released the craft, and the astronauts were flying free in the LM. They backed away and rotated the module so that Scott, in the command module, could see that all the legs were down and extended, and that there were no physical failures in the craft itself. Then they fired the descent engine just enough to move the LM into a parallel orbit about three miles away from the command module. The mechanics of the orbit were such that the LM was on its own, but twice during each swing around the Earth? the two spacecraft were close enough so that Scott could initiate rescue operations should anything have happened to the EM.For nearly six hours the two astronauts in the LM rehearsed the possible phases of the lunar approach and departure. They exercised the reaction control systems, fired the descent engine again, then jettisoned the descent stage, and then fired the ascent engine for the first time in space. From their adjusted position about 10 miles below and 80 miles behind the command module, they began their approach to a rendezvous and docking, much the same as the actual event to take place later on Apollo 11. The first phase of their rendezvous terminated temporarily with about a 100 foot separation, so that both spacecraft could be photographed. Then they docked, a solid and clean joining that verified the crews' training and the performance of the docking and locking mechanisms. They jettisoned the ascent stage, and remotely fired its engine to insert it into a highly elliptical orbit around the Earth.

|

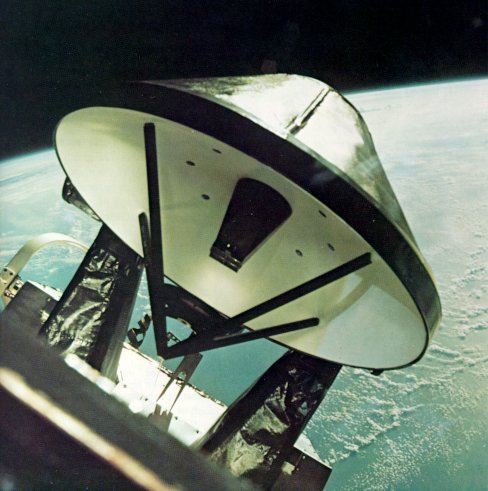

| The rendezvous radar antenna on the LM, untried in space, was photographed through a CM window by one of the Apollo 9 crew, perhaps in anticipation of the fact that it would soon be unstowed, powered up, and put to the all-important test. A critical and sophisticated part of the rendezvous system, it worked beautifully when tried two days roter. The curved metal strap at the extreme left, not part of the antenna, is a handrail to be grasped by an Astronaut floating outside the spacecraft. |

From here on, the rest of the mission was almost an anticlimax, because the performance of the spacecraft left no doubt as to its ability to make the lunar trip, complete with landing and departure. But there was still work to be done, and so for the remaining five days in orbit, the crew again and again exercised the service propulsion system, once to lower the perigee of their Earth orbit, once to test the propellant staging system, and once to head home to Earth. On the last four days, they also did a series of landmark tracking experiments, using visual sightings of Earth features which were observed and photographed. They also made a number of photographs with a multiple-camera assembly using different film emulsions to obtain pictures in different portions of the photographic spectrum. These were further augmented by pictures taken almost simultaneously with hand-held cameras, using conventional films.

Once out of orbit, following the eighth successive firing of the service propulsion system, the reentry was normal. They landed right on their target in the Atlantic, 241 hours after takeoff, and were recovered quickly by Navy helicopters.

Apollo 10 was different, because it did go to the Moon- or at least within 47,000 feet of it- in its rehearsal of the Apollo 11 mission. There had been some speculation about whether or not the crew might have landed, having gotten so close. They might have wanted to, but it was impossible for that lunar module to land. It was an early design that was too heavy for a lunar landing, or, to be more precise, too heavy to be able to complete the ascent back to the command module. It was a test module, for the dress rehearsal only, and that was the way it was used. Besides, the discipline on the Apollo program was such that no crew would have made such a decision on its own in any event.

| In the cheerful mood prevailing when the three crew members were back together, Dave Scott mugs for Rusty Schweickart's camera. Here he shows how he, when alone in the command module, had had to peer against the glare to catch his first glimpse of the LM as it flew back in rendezvous. |

| Five hard days of carefully doing what had never been done before shows in the strained face of Apollo 9 Commander Jim McDivitt, normally a relaxed and equable man. Attempting to describe the cool courage of McDivitt and Schweickart when they went off for the first time over the horizon in the unlandabie LM, some observers declared it the bravest act since man first ate a raw oyster. |

Thomas P. Stafford was the Apollo 10 mission commander, with command module pilot John W. Young and lunar module pilot Eugene A. Cernan. They were launched on schedule at 11:49 AM, on May 18, 1969, about two and one-half months after Apollo 9 had set out on its successful test flight.

| Next |