Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

FIFTEEN MINUTES OF POWER LEFT

With only 15 minutes of power left in the CM, CapCom told us

to make our way into the LM. Fred and I quickly floated through

the tunnel, leaving Jack to perform the last chores in our

forlorn and pitiful CM that had seemed such a happy home less

than two hours earlier. Fred said something that strikes me as

funny as I read it now: "Didn't think I'd be back so soon." But

nothing seemed funny in real time on that 13th of April, 1970.

| | |

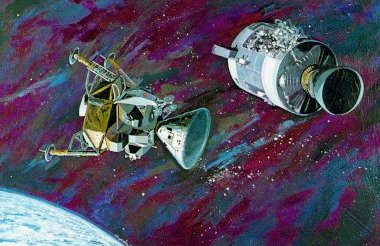

Blast-gutted service module was set adrift from

the combined command module and lunar module just four hours

before Earth reentry. Mission Control had insisted on

towing the wrecked service module for 300,000 miles

because its bulk protected the command module's heat

shield from the intense cold of space. The astronauts next

revived the long-dormant command module and prepared

to leave their lunar module lifeboat.

|

There were many, many things to do. In the first place, did

we have enough consumables to get home? Fred started calculating,

keeping in mind that the LM was built for only a 45-hour

lifetime, and we had to stretch that to 90. He had some data from

previous LMs in his book -- average rates of water usage related to

amperage level, rate of water needed for cooling. It turned out

that we had enough oxygen. The full LM descent tank alone would

suffice, and in addition, there were two ascent-engine oxygen

tanks, and two backpacks whose oxygen supply would never be used

on the lunar surface. Two emergency bottles on top of those packs

had six or seven pounds each in them. (At LM jettison, just

before reentry, 28.5 pounds of oxygen remained, more than half of

what we started with.)

We had 2181 ampere hours in the LM batteries. We thought

that was enough if we turned off every electrical power device

not absolutely necessary. We could not count on the precious CM

batteries, because they would be needed for reentry after the LM

was cast off. In fact, the ground carefully worked out a

procedure where we charged the CM batteries with LM power. As it

turned out, we reduced our energy consumption to a fifth of

normal, which resulted in our having 20 percent of our LM

electrical power left when we jettisoned Aquarius. We did have

one electrical heart-stopper during the mission. One of the CM

batteries vented with such force that it momentarily dropped off

the line. We knew we were finished if we permanently lost that

battery.

| | |

The jettisoning of elements during the critical

last hours of the Apollo 13 mission is shown in this sequence

drawing. When the lifesaving LM was shoved off by

tunnel pressure about an hour before splashdown, everyone

felt a surge of sentiment as the magnificent craft

peeled away. Its maker, Grumman, later jokingly sent

a bill for more than $400,000 to North American Rockwell

for "towing" the CSM 300,000 miles.

|

Water was the real problem. Fred figured that we would run

out of water about five hours before we got back to Earth, which

was calculated at around 151 hours. But even there, Fred had an

ace in the hole. He knew we had a data point from Apollo 11,

which had not sent its LM ascent stage crashing into the Moon, as

subsequent missions did. An engineering test on the vehicle

showed that its mechanisms could survive seven or eight hours in

space without water cooling, until the guidance system rebelled

at this enforced toasting. But we did conserve water. We cut down

to six ounces each per day, a fifth of normal intake, and used

fruit juices; we ate hot dogs and other wet-pack foods when we

ate at all. (We lost hot water with the accident and dehydratable

food is not palatable with cold water.) Somehow, one doesn't get

very thirsty in space and we became quite dehydrated. I set one

record that stood up throughout Apollo: I lost fourteen pounds,

and our crew set another by losing a total of 31.5 pounds, nearly

50 percent more than any other crew. Those stringent measures

resulted in our finishing with 28.2 pounds of water, about 9

percent of the total.

| | |

Carbon dioxide would poison the astronauts unless

scrubbed from the lunar module atmosphere

by lithium hydride

canisters. But the lunar module had only enough

lithium hydride for 4 man-days - plenty for the lunar landing but not

the 12 man-day's worth needed now. Here Deke Slayton (center)

explains a possible fix to (left to right) Sjoberg,

Kraft, and Gilruth. At left is Flight Director Glynn Lunney.

|

Fred had figured that we had enough lithium hydroxide

canisters, which remove carbon dioxide from the spacecraft. There

were four cartridge from the LM, and four from the backpacks,

counting backups. But he forgot that there would be three of us

in the LM instead of the normal two. The LM was designed to

support two men for two days. Now it was being asked to care for

three men nearly four days.

|