Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

THE PLAN IN RETROSPECT

In thinking back over the flights of Apollo, I am impressed at the intrinsic excellence

of the plan that had evolved. I have, of course, somewhat oversimplified its evolution,

and there were times when we became discouraced, and when it seemed that the

sheer scope of the task would overwhelm us in some areas there were surprises and other

areas proceeded quite naturally and smoothly.

|

Gemini launches drew hundreds of thousands of

spectators, awed by the roar, flame, and smoke of

the big Titan II booster. Viewers clogged the highways

and camped by roadsides. Millions of others

watched launchings an television, and the astronauts

received tumultuous welcomes on their return. The

launch at left is Gemini V, which carried Astronauts

Cooper and Conrad for 120 revolutions of the Earth

during August 1965. Fuel cells had their first space

test an this flight.

|

| | |

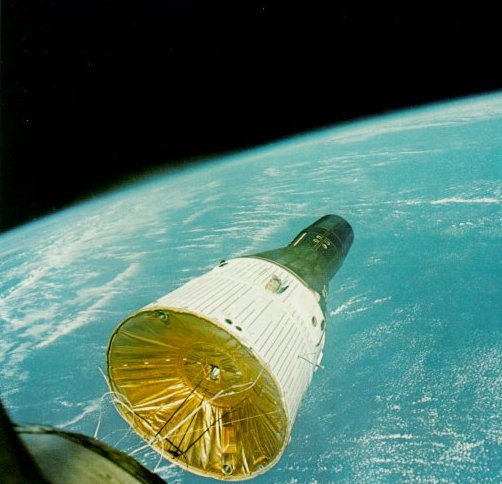

First U.S. rendezvous in space occurred an December 15,

1965, when Gemini VI found and came

within 6 feet of Gemini VIl, which had been

launched 11 days earlier. Picture below was shot by

Tom Stafford, aboard Gemini VI with Wolly Schirra.

The other spacecraft, shown here at a range of 37

feet, was flown by astronauts Borman and Lovell in

a flight lasting more than 330 hours. Rendezvous

proved entirely feasible but tricky to manage with

minimum fuel use.

|

The most cruel surprise in the program was the loss of three astronauts in the

Apollo fire, which occurred before our first manned flight. It was difficult for the country

to understand how this could have occurred, and it seemed for a time that the program

might not survive. I believe that the self-imposed discipline that resulted, and the

ever-greater efforts on quality, enhanced our chances for success, coming as they did

while the spacecraft was being rebuilt and final plans formulated.

The pogo problem was another surprise. Like the fire, it showed how dif'ficult

it was to conquer this new ocean of space. Fortunately, intensive and brilliant work

with the big Saturns solved the problem with the launch rocket, permitting the flights to

proceed without mishap.

| | |

Astronaut Edward H. White

was the first American to step

outside in space. Jim McDivitt,

Gemini IV's command pilot,

took this picture on June 3,

1965. A 25-foot umbilical line

and tether linked White to the

spacecraft. In his left hand

is an experimental personal

propulsion unit. His chest

pack contained an eight-minute

emergency oxygen supply, as

a backstop.

|

| | |

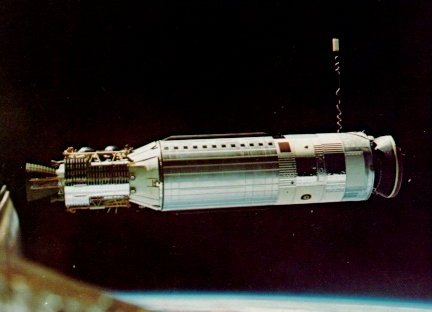

An Agena target vehicle was

docked with by Gemini VIll on

March 16, 1966. A short-circuited

thruster set the two craft

spinning dangerously, forcing

Astronauts Armstrong and

Scott to end the mission.

|

We had planned a buildup of our flights, starting with a simple Earth-orbit flight

of the command and service modules (Apollo 7), to be followed by similar trials with

the lunar module (LM) added, for tests of rendezvous and docking and various burns

of the LM engines (Apollo 9). These tests would have then been followed by flights

to Lunar orbit with the LM scouting the landing but not going all the way in (Apollo

10), and then the landing (Apollo 11).

After Apollo 7, however, the LM was not yet ready and the opportunity occurred

to fly to the Moon with command and service module (CSM) only. This flight (Apollo 8)

was to give us many benefits early in the progam. Technically, it gave us information

on our communication and tracking equipment for later missions, a close view of

our landing sites, and experience in cislunar space with a simplified mission. Politically,

it may have assured us of being first to the Moon, since the stepped-up schedule

precluded the Russians from flying a man around the Moon with their Zond before we

reached the Moon following our previously scheduled missions.

The flights came off almost routinely following Apollo 8 on through the first lunar

landing and the flight to the Surveyor crater. But Apollo 13 was to see our first major

inflight emergency when an explosion in the service module cut off the oxygen supply

to the command module. Fortunately, the LM was docked to the CSM, and its oxygen

and electric power, as well as its propulsion rocket, were available. During the 4-day

ordeal of Apollo 13, the world watched breathlessly while the LM pushed the stricken

command module around the Moon and back to Earth. Precarious though it was,

Apollo 13 showed the merit of having separate spacecraft modules, and of training of

flight and gound crews to adapt to emergency. The ability of the flight directors on the

ground to read out the status of flight equipment, and the training of astronauts to meet

emergencies, paid off on this mission.

Apollo surely is a prototype for explorations of the future when we again send

men into space to build a base on the Moon or to explore even farther away from Earth.

|