Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

A TRAGIC FIRE TAKES THREE LIVES

Apollo in January 1967 was adjudged almost ready for its first manned flight in

Earth orbit. And then disaster. A routine test of Apollo on the launching pad at Cape

Kennedy. Three astronauts - Grissom, White, and Chaffee - in their spacesuits in a

100-percent oxygen environment. A tiny spark, perhaps a short circuit in the wiring.

It was all over in a matter of seconds. Yet it would be 21 months before Apollo would

again be ready to fly.

By April 1967, when I was given the Apollo spacecraft job, an investigation board

had completed most of its work. The board was not able to pinpoint the exact cause

of the fire, but this only made matters worse bccause it meant that there were probably

flaws in several areas of the spacecraft. These included the cabin environment on the

launch pad, the amount of combustible material in the spacecraft, and perhaps most

important, the control (or lack of control) of changes.

Apollo would fly in space with a pure oxygen atmosphere at 5 psi (pounds per

square inch), about one-third the pressure of the air we breathe. But on the launching

pad, Apollo used pure oxygen at 16 psi, slightly above the pressure of the outside air.

Now it happens that in oxygen at 5 psi things will generally burn pretty much as they

do in air at normal pressures. But in 16 psi oxygen most nonmetallic materials will

burn explosively; even steel can be set on fire. Mistake number one: Incredible as it

may sound in hindsight, we had all been blind to this problem. In spite of all the care,

all the checks and balances, all the "what happens if's", we had overlooked the hazard

on the launching pad.

| | |

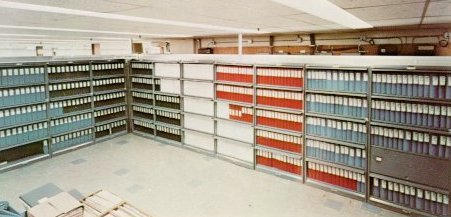

The pedigree of just one Apollo

spacecraft took this many books.

A mind-numbing degree of documentation contributed to reliability,

safety, and success. lf one batch of

one alloy in one part was found to

be faulty, for example, a search

could show if the bad material had

found its way into other spacecraft,

to lie in wait there.

|

| | |

Inspecting the new hatch, Wally Schirra makes

sure his crew cannot be trapped as was the

crew that died in the terrible Apollo spacecraft

fire. Opening outward (to swing freely if pressure

built up inside), the new hatch had to be much

sturdier than the old inward-opening one.

The complicated latch sealed against tiny

leaks but allowed very rapid release.

|

Most nonmetallic things will burn - even in air or 5 psi oxygen - unless they are

specially formulated or treated. Somehow, over the years of development and test, too

many nonmetals had crept into Apollo. The cabin was full of velcro cloth, a sort of

space-age baling wire, to help astronauts store and attach their gear and checklists.

There were paper books and checklists, a special kind of plastic netting to provide more

storage space, and the spacesuits themselves, made of rubber and fabric and plastic.

Behind the panels there were wires with nonmetallic insulation, and switches and circuit

breakers in plastic cases. There were also gobs of insulating material called RTV.

(In Gordon Cooper's Mercury flight, some important electronic gear had malfunctioned

because moisture condensed on its uninsulated terminals. The solution for

Apollo had been to coat all electronic connections with RTV, which performed admirably

as an insulator, but, as we found out later, burned in an oxygen environment.)

Mistake number two: Far too much nonmetallic material had been incorporated in

the construction of the spacecraft.

| | |

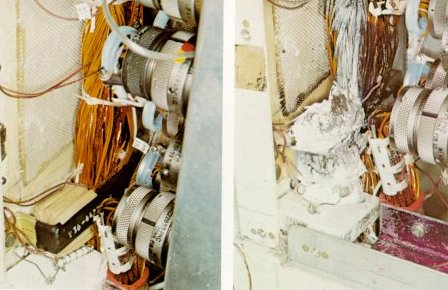

After the fire, flammability and

self-extinguishment were key concerns.

In the test setup at right

a wiring bundle is purposely ignited,

using the white flammable

material within the coil near the

bottom to simulate a short circuit (left).

Picture at right shows the

aftermath: a fire that initially

propagated but soon extinguished

itself. It took great effort and

ingenuity to devise materials that

would not burn violently in the

pure-oxygen atmosphere. lf a

test was not satisfactory and a

fire did not put itself out, the

material or wire routing was redesigned

and then retested.

|

| | |

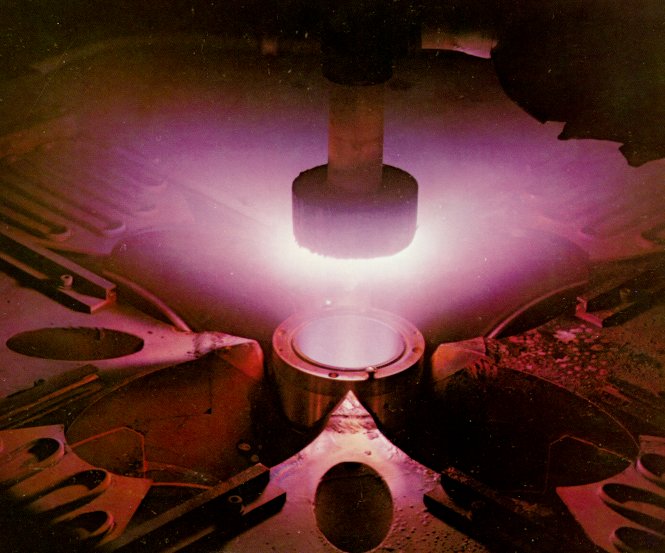

Seared at temperatures hotter than the surface

of the Sun, a sample of heat-shield material

survives the blast from a space-age furnace.

Machines used to check out Apollo components

were as demanding as those in the mission itself,

because a mistake or miscalibration during

preflight trials could easily lay the groundwork

for disaster out in unforgiving space.

|

There is an old saying that airplanes and spacecraft won't fly until the paper

equals their weight. There was a time when two men named Orville and Wilbur Wright

could, unaided, design and build an entire airplane, and even make its engine. But

those days are long gone. When machinery gets as complex as the Apollo spacecraft,

no single person can keep all of its details in his head. Paper, therefore, becomes of

paramount importance: paper to record the exact confiugration; paper to list every

nut and bolt and tube and wire, paper to record the precise size, shape, constitution.

history, and pedigree of every piece and every part. The paper tells where it was made,

who made it, which batch of raw materials was used, how it was tested, and how it

performed. Paper becomes particularly important when a change is made, and changes

must be made whenever design, engineering, and development proceed simultaneously

as they did in Apollo. There are changes to make things work, and changes to replace a

component that failed in a test, and changes to ease an astronaut's workload or to make

it difficult to flip the wrong switch.

| | |

Meant to fly in a vacuum, and to survive fiery reentry,

the command module had also to serve as a

boat. Although its parachutes appeared to lower it

gently, its final impact velocity was still a jarring

20 mph. Tests like this one established its resistance

to the mechanical and thermal shocks of impact, and its ability to float afterward.

|

| | |

Hitting land was possible, even though water was the

expected landing surface. For this, a shock-absorbing

honeycomb between the heat shield and the inner shell

was one protection, along with shock absorbers on the

couch supports. A third defense against impact was

the way each couch was molded to its astronaut's size

and shape, to provide him with the maximum support.

|

Mistake number three: In the rush to prepare Apollo for flight, the control of

changes had not been as rigorous as it should have been, and the investigation board

was unable to determine the precise detailed configuration of the spacecraft, how it was

made, and what was in it at the time of the accident. Three mistakes, and perhaps more,

added up to a spark, fuel for a fire, and an environment to make the fire explosive in its

nature. And three fine men died.

| | |

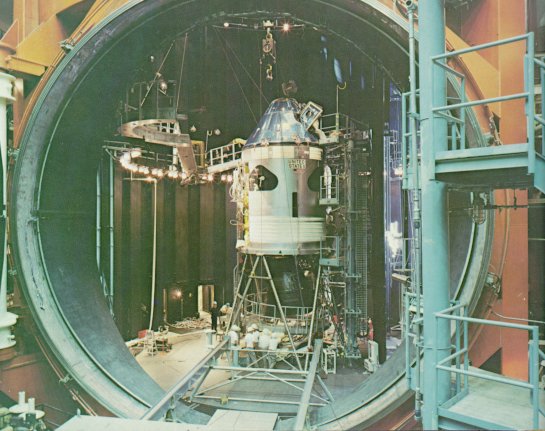

Through the portal of a huge test chamber,

the command and service modules can be seen in preparation for

a critical test: a simulated run in the entire space

environment except for weightlessness. In this vacuum chamber

one side of the craft can be cooled to the temperature of black

night in space while the opposite side is broiled

by an artificial Sun. Will coolant lines freeze or boil?

Will the cabin stay habitable?

|

|