OUR FIRST CLOSE LOOK

The first project to emerge from this government/university team was named Ranger, to connote the exploration of new frontiers. Subsequently Surveyor and Prospector echoed this naming theme. (Planetary missions adopted nautical names such as Mariner, Voyager, and Viking.) The guideline instructions furnished JPL for Ranger read in part: "The lunar reconnaissance mission has been selected with the major objective . . . being the collection of data for use in an integrated lunar-exploration program. . . . The [photographic] system should have an overall resolution of sufficient capability for it to be possible to detect lunar details whose characteristic dimension is as little as 10 feet." Achieving this goal did not come about easily.

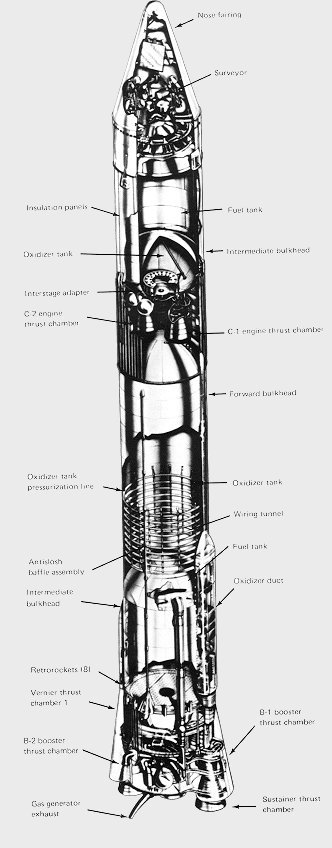

| The Surveyor mission had been conceived in 1959 as a scheme to soft-land scientific instruments an the Moon's surface. It was a highly ambitious plan that required both development of a radical new launch vehicle and the new technology of a closed-loop, radar-controlled automated landing. The cutaway drawing shows the Atlas-Centaur launch vehicle. The Atlas-Centaur, a major step forward in rocket propulsion, was the first launch vehicle to use the high-energy propellant combination of hydrogen and oxygen. Its new Centaur upper stage, built by General Dynamics, had two Pratt & Whitney RL-10 engines of 15,000-lb thrust each. The first stage was a modified Atlas D having enlarged tanks and increased thrust. |

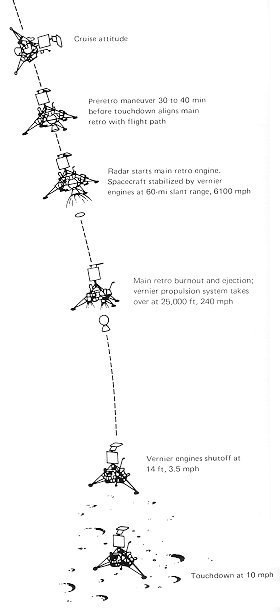

| The main events in a successful Surveyor landing sequence. |

The initial choice of launch vehicle for the Ranger was the USAF Atlas, mated with a new upper stage to be developed by JPL, the Vega. Subsequently NASA cancelled the Vega in favor of an equivalent vehicle already under development by the Air Force, the Agena. This left JPL free to concentrate on the Ranger. The spacecraft design that evolved was very ambitious for its day, incorporating solar power, full three-axis stabilization, and advanced communications. Clearly JPL also had its eye on the planets in formulating this design.

|

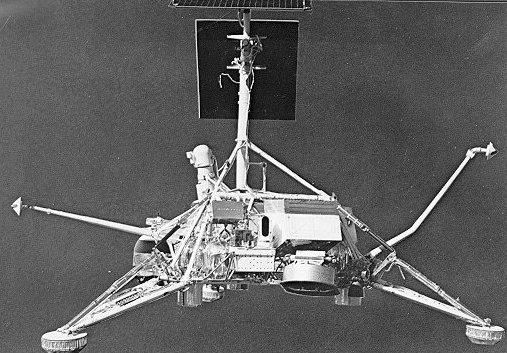

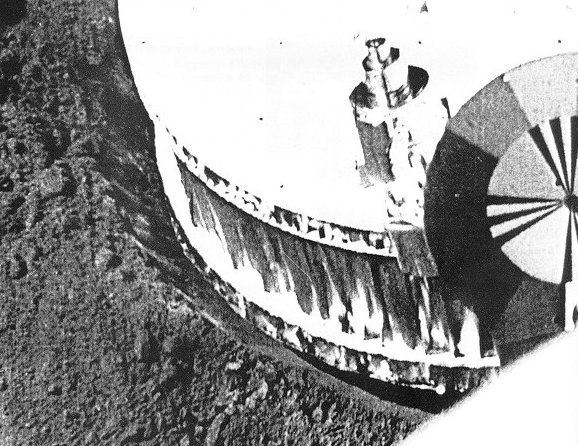

| The spidery Surveyor consisted of a tubular framework perched an three shock-absorbing footpads. Despite ist queer appearance, it incorporated some of the most sophisticated automatic systems man had ever hurled into space (see specifications below). The first one launched made a perfect soft landing an the Moon, radioing back to Earth a rich trove of imagery and data. Seven were launched in all; one tumbled during course correction, one went mysteriously mute during landing, and the remaining five were unqualified successes. |

| WEIGHT

Weight at launch 2193 lb Landed weight 625 lb |

| POWER

Solar panel: 90 watts Batteries: 230 ampere-hours |

| COMMUNICATIONS

Dual transmitters: 10 watts each |

| GUIDANCE AND CONTROL

Inertial reference: 3-axis gyros Celestial reference: Sun and Canopus sensors Attitude control: cold gas jets Terminal landing: automated closed loop, with radar altimeter and doppler velocity sensor |

| PROPULSION

Main retrorocket: 9000-lb solid fuel Vernier retrorockets: throttable between 30- and 102-lb thrust each |

| TV CAMERA

Focal length: 25 or 100 mm Aperture: f/4 to f/22 Resolution: 1 mm at 4 m |

|

Typical Surveyor Specifications |

|

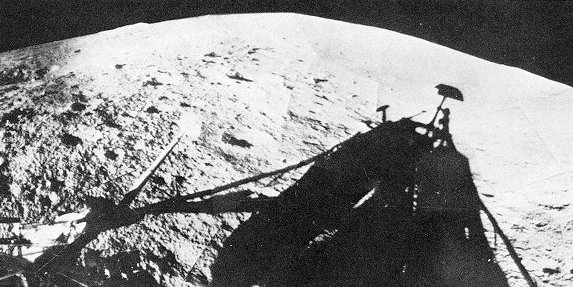

| Its insectlike shadow was photographed by Surveyor I on the desolate surface of Oceanus Procellarum. During the long lunar day it shot 10,386 pictures, including the 52 in this mosaic. The noon temperature of 235° F dropped to 250° below zero an hour after the Sun went down. |

Of a total of nine Rangers launched between 1961 and 1965, only the last three succeeded. From the six failures we learned many lessons the hard way. Early in the program, an attempt was made to protect the Moon from earthly contamination by sterilizing the spacecraft in an oven. This technique, which is now being used on the Mars/Viking spacecraft, had to be abandoned at that time when it wreaked havoc with Ranger's electronic subsystems.

In the first two launches in 1961 the new Agena B upper stage failed to propel the Ranger out of Earth orbit. Failures in both the launch vehicle and spacecraft misdirected the third flight. On the fourth flight the spacecraft computer and sequencer malfunctioned. And on the fifth flight a failure occurred in the Ranger power system. The U.S. string of lunar missions with little or no success had reached fourteen. Critics were clamoring that Ranger was a "shoot and hope" project. NASA convened a failure review board, and its studies uncovered weaknesses in both the design and testing of Ranger. Redundancy was added to electronic circuits and test procedures were tightened. As payload Ranger VI carried a battery of six television cameras to record surface details during the final moments before impact. When it was launched on January 30, 1964, we had high confidence of success. Everything seemed to work perfectly. But when the spacecraft plunged to the lunar surface, precisely on target, its cameras f ailed to turn on. I will never forget the feeling of dismay in the JPL control room that day.

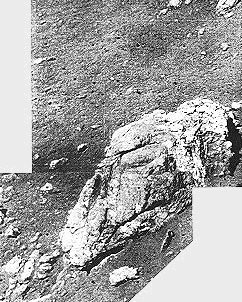

| The first lunar soft landing was accomplished by Russia's Luna 9 on February 3, 1966, about 60 miles northeast of the crater Calaverius. Its pictures showed details down to a tenth of an inch five feet away. They indicated no loose dust layer, both rounded and angular rock fragments, numerous small craters, some with slope angles exceeding 40 degrees, and generally granular surface material. These results increased confidence that the Moon was not dangerously soft for a manned landing. |

|

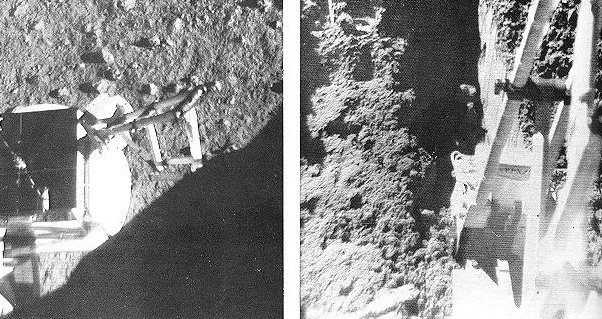

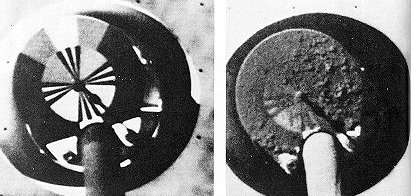

| Surveyor I televised excellent pictures of the depth of the depression in the lunar soil made by its footpad when it soft-landed on June 2, 1966, four months after Luna 9. Calculations from these and similar images set at rest anxieties about the load-bearing adequacy of the Moon. Some scientists had theorized that astronauts could be engulfed in dangerously deep dust layers, but Surveyor's footpad pictures, as well as the digging done by the motorized scoop on board, indicated that the Moon would readily support the LM and its astronauts. |

But we all knew we were finally close. Careful detective work with the telemetry records identified the most probable cause as inadvertent turn-on of the TV transmitter while Ranger was still in the Earth's atmosphere, whereupon arcing destroyed the system. The fix was relatively simple, although it delayed the program for three months. On July 28, 1964, Ranger VII was launched on what proved to be a perfect mission. Eighteen minutes before impact in Oceanus Procellarum, or Ocean of Storms, the cameras began transmitting the first of 4316 excellent pictures of the surface. The final frame was taken only 1400 feet above the surface and revealed details down to about 3 feet in size. It was a breathless group of men that waited the arrival of the first quick prints in the office of Bill Pickering, JPL's Director. The prints had not been enhanced and it was hard to see the detail because of lack of contrast. But those muddy little pictures with their ubiquitous craters seemed breathtakingly beautiful to us.

By the time of the Ranger VII launch, the Apollo program had already been underway for three years, and Ranger had been configured and targeted to scout possible landing sites. Thus Ranger VIII was flown to a flat area in the Sea of Tranquility where it found terrain similar to that in the Ocean of Storms: gently sloping plains but craters everywhere. It began to look as if the early Apollo requirement of a relatively large craterless area would be difficult to find. As far as surface properties were concerned, the Ranger could contribute little to the scientific controversy raging over whether the Moon would support the weight of a machine - or a man.

|

| Like a tiny back hoe, the surface sampler fitted to some Surveyors could dig trenches in the lunar soil. Above, the smooth vertical wall left by the scoop indicated the cohesiveness of the fine lunar material. Variations in the amount of current drawn by the sampler motor gave indication of the digging effort needed. At left above, the sampler is shown coming to the rescue when the head of the alpha-scattering instrument failed to deploy on command. After two gentle downward nudges from the scoop, the instrument dropped to the surface. |

| "A dinosaur's skull" was the joking name that Surveyor I controllers used for this rock. Geologists on the team were more solemn: "A rock about 13 feet away, 12 by 18 inches, subangular in shape with many facets slightly rounded. Lighter parts of the rock have charper features, suggesting greater resistance to erosion." |

|

| Surveyor VI hopped under its own power to a second site about eight feet from its landing spot. This maneuver made it possible to study the effect of firing rocket engines that impinged an the lunar surface. Picture at left below shows a photometric chart attached to an omni-antenna, which was clean after first landing. Afterward, the chart was coated with an adhering layer of fine soil blasted out of the lunar surface. |

To get maximum resolution of surface details, it was necessary to rotate Ranger so that the cameras looked precisely along the flight path. This was not done on Ranger VII in order to avoid the risk of sending extra commands to the attitude-control system. I recall that on Ranger VIII JPL requested permission to make the final maneuver. NASA denied permission - we were still unwilling, after the long string of failures, to take the slightest additional risk. It was not until Ranger IX that JPL made tbe maneuver and achieved resolution approaching 1 foot in the last frame. This final Ranger, launched on March 21, 1965, was dedicated to lunar science rather than to reconnaissance of Apollo landing sites. It returned 5814 photographs of the crater Alphonsus, again showing craters within craters, and some rocks. Despite its dismal beginnings the Ranger program was thus concluded on a note of success. Proposed follow-on missions were cancelled in favor of upcoming Surveyor and Orbiter missions, whose development had been proceeding concurrently.

| Next |