Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

MAPPING AND SITE SELECTION

Meanwhile the third member of the automated lunar exploration team had

already completed its work. The fifth and last Lunar Orbiter had been launched on

August 1, 1967, nearly half a year earlier. When JPL and Hughes began to experience

difficulties with Surveyor development, and with the Centaur in deep trouble, NASA

decided to back up the entire proaram with a different team and different hardware.

The Surveyor Orbiter concept was scrapped, and NASA's Langley Research Center

was directed to plan and carry out a new Lunar Orbiter program, based on the less

risky Atlas-Acena D launch vehicle. Langley prepared the necessary specifications

and Boeing won the job. Boeing's proposed design was beautifully straightforward

except for one feature, the camera. Instead of being all-electronic as were prior space

cameras, the Eastman Kodak camera for the Lunar Orbiter made use of 70-mm film

developed on board the spacecraft and then optically scanned and telemetered to

Earth. Low-speed film had to be used so as not to be fogged by space radiation. This

in turn required the formidable added complexity of image-motion compensation during

the instant of exposure. Theoretically, objects as small as three feet could be seen

from 30 nautical miles above the surface. If all worked well, this system could provide

the quality required for Apollo, but it was tricky, and it barely made it to the launch

pad in time to avoid rescheduling.

| | |

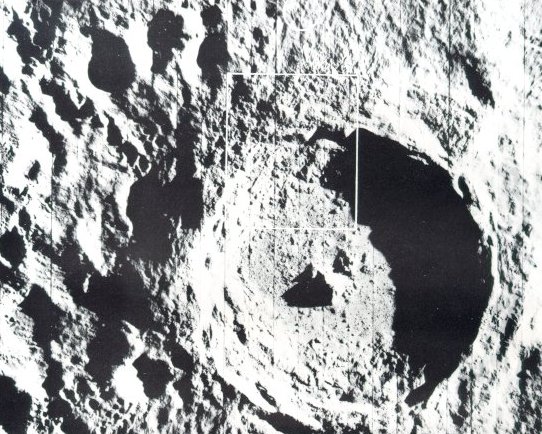

The youngest big crater on the Moon

is Tycho, which is about 53 miles

across and nearly 3 miles deep. These

Orbiter V photographs reveal its intricate structure.

(Area in the rectangle above is pictured in higher

resolution below.) A high central peak

arises from the rough floor, and the

crater wall has extensively slumped.

The comparative scarcity of small

craters within Tycho indicate its relatively

recent origin. Flow features

seen in both pictures could have been

molten lava, volcanic debris, or

fluidized impact-ejected material.

Surveyor VII landed about 18 miles

north of Tycho, in the area indicated

by the white circle above. Enlargements of these pictures show an

abundance of fissures and large fractured blocks, particularly near the

uppermost wall scarp.

|

The Orbiter missions were designed to photograph all possible Apollo landing

sites, to measure meteoroid flux around the Moon, and to determine the lunar gravity

field precisely, from accurate tracking of the spacecraft. Orbiter did all

these things - and more.

As the primary objectives for Apollo program were essentially accomplished

on completion of the third mission, the fourth and fifth missions were devoted largely

to broader, scientific objectives - photography of the entire lunar nearside

during Mission IV and photography of 36 areas of particular scientific interest on the near side

during Mission V. In addition, 99 percent of the far side was photographed in more

detail than Earth-based telescopes had previously photographed the front.

| | |

This breath-taking view was

one of Lunar Orbiter II's most

captivating photographic

achievements. For many people who had only seen an

Earth-based telescopic view

looking down into the crater

Copernicus, this oblique view

suddenly transformed that

static lunar feature into a

dramatic landscape with rolling mountains, sweeping

palisades, and tumbling land-slides. The crater Copernicus

is about 60 miles in diameter,

2 miles deep, with 3000-foot

cliffs. Peaks near the center

of the crater form a mountain

range about 10 miles long

and 2000 feet high. Lunar

Orbiter II recorded this "picture of the year" on

November 28, 1964, from 28.4 miles

above the surface when it

was about 150 miles due

south of the crater.

|

The first Lunar Orbiter spacecraft was launched on August 10, 1966, and photographed

nine primary and seven secondary sites that were candidates for Apollo landings.

The medium-resolution pictures were of good quality, but a malfunction in the

synchronization of the shutter caused loss of the high-resolution frames. In addition,

some views of the far side and oblique views of the Earth and Moon were also taken

(see here).

When we made the suggestion of taking this "Earthrise" picture, Boeing's

project manager, Bob Helberg, reminded NASA that the spacecraft maneuver

required constituted a risk that could jeopardize the company profit, which was tied

to mission success. He then made the gutsy decision to go ahead anyway and we got

this historic photograph.

|

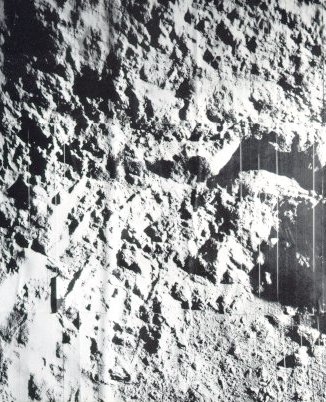

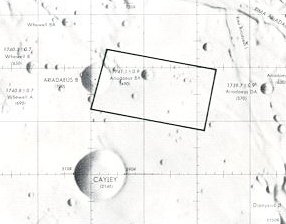

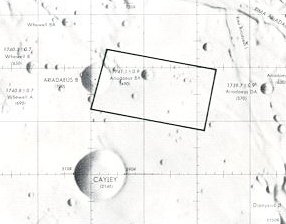

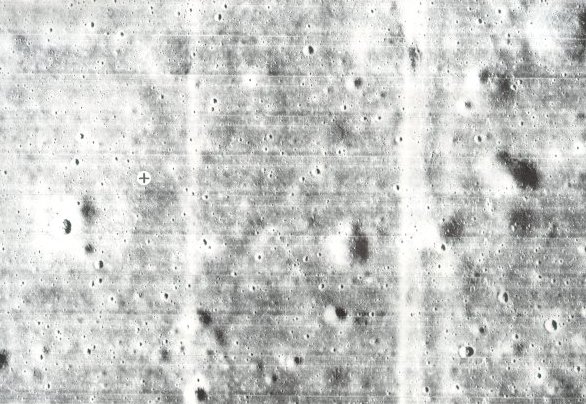

The best maps weren't good enough,

even though they were based an years of

telescopic photography from Earth. In

early planning, the rectangle in the map

at left was a possibility os a landing

site. The handful of craters shown, it

was innocently thought, should be easy

enough to dodge during the last moments

of a piloted landing. The site was an 11- by 20-mile rectangle located

in the highlands west of Mare Tranquillitatis.

|

| | |

The truth about this site was revealed by the accurate

eye of Lunar Orbiter II: it was far too rough

to be attempted in an early manned landing.

In fact, Orbiter pictures showed that parts of the Moon

were as rough as a World War I battlefield, with

craters within craters, and all parts of the surface

tilled and pulverized by a rocky rain. No areas were

found smooth enough to meet the original

Apollo landing-site criteria, but a few approached

it and the presence of a skilled pilot aboard the

LM to perform last-minute corrections mode landings

possible. The high-quality imagery returned

by the Orbiters also returned a harvest of

new scientific information.

|

The next two Lunar Orbiter missions were launched on November 6, 1966, and

February 4, 1967. They provided excellent coverage of all 20 potential Apollo landing

sites, additional coverage of the far side and other lunar

features of scientific interest,

and many oblique views of lunar terrain as it might be seen by an orbiting astronaut.

One of these was a dramatic oblique photograph of the crater Copernicus, which

NASA's Associate Administrator, Dr. Robert C. Seamans, unveiled at a professional

society conference in Boston and which drew a standing ovation and designation as

"picture of the year". Among the possible Apollo sites photographed by Orbiter III

was the landing site of Surveyor I. Careful photographic detective work found the

shining Surveyor and its dark shadow among the myriad craters.

The Apollo site surveys yielded surprises. Some sites that had looked promising

in Earth-based photography were totally unacceptable. No sites were found to be as

free of craters as had been originally specified for Apollo, so the Langley lunar landing

facility was modified to give astronauts practice at crater dodging. Since the basic

Apollo photographic requirements were essentially satisfied by the first three flights,

the last two Orbiters launched on May 4 and August 1, 1967, were

placed in high near-polar

orbits from which they completed coverage of virtually the entire lunar surface.

The other Orbiter experiments were also productive. No unexpected levels of

radiation or meteoroids were found to offer a threat to astronaut safety. Studies of

the Orbiter motion, however, revealed relatively large gravitational variations due to

buried mass concentrations - the phrase was soon telescoped to "mascons" - in the

Moon's interior. This alerted Apollo planners to account properly for mascon perturbations

when calculating precise Apollo trajectories.

With the completion of the Ranger, Surveyor, and Orbiter programs, the job of

automated spacecraft in scouting the way for Apollo was done. Our confidence was high

that few unpleasant surprises would wait our Apollo astronauts on the lunar surface.

The standard now passed from automated machinery to hands of flesh and blood.

THE SELECTION OF APOLLO LANDING SITES

The search for places for astronauts to land began with telescopic

maps and other observations from

the Earth, and Ranger Photos. The

site-selection team considered landing constraints, potentials for

scientific exploration, and options if a

launch was delayed, which shifted

chosen sites to the west. The team

then designated a group of lunar

areas as targets for Surveyors and

Lunar Orbiters.

From the Orbiters' medium-resolution photos, mosaics were made

and searched for geologic and

topographic features that could

make a landing risky: roughness,

hills, escarpments, craters, boulders,

and steep slopes.

Navigation errors could cause an

Apollo landing module to miss a

target point up to 1.5 miles north

or south and 2.5 miles east or west.

So ellipses were drawn an the

mosaics around possible target

areas. Those ellipses represented

50, 90, and 100 percent dispersion

possibilities. The surfaces within

them were then examined to select

the target points that appeared to

be least hazardous.

Flight-path clearance problems

were considered next. This is illustrated by drawing diverging lines

eastward for 35 miles from the

elliptical areas that otherwise looked

best on the mosaics.

| |

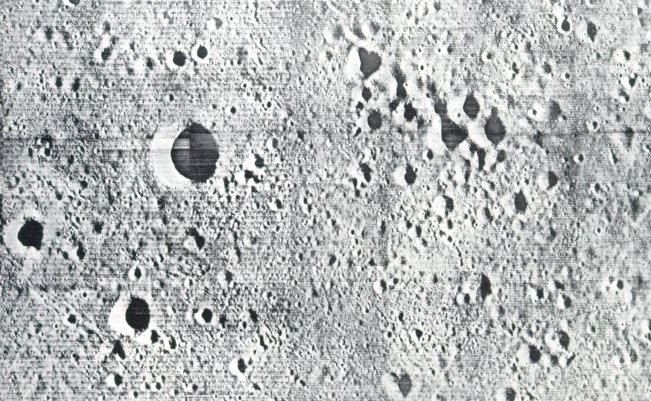

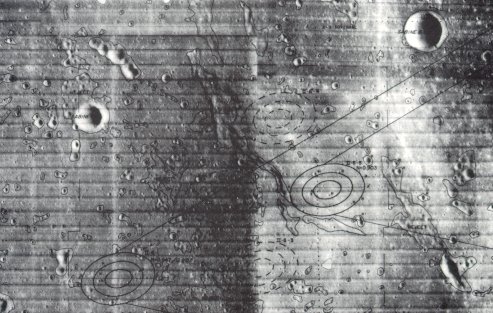

A typical marked mosaic is reproduced above. It is a view of a

region in Mare Tranquillitatis, and

the area within the set of ellipses

at the far left was chosen as the

target for the first manned landing.

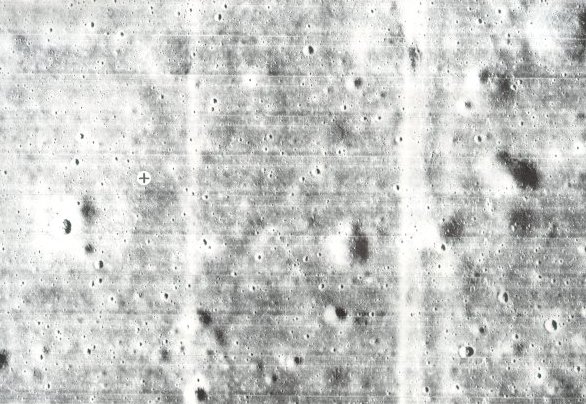

Before it was selected, high-resolution Orbiter Photos were used to

examine details within the landing

ellipses. In those Photos surface

irregularities as small as 3 feet

could be seen. One such mosaic is

reproduced below.

The black cross in a white circle

marks the spot

where the Apollo 11 astronauts'

landing module descended. It was in

an elliptical target area only 200

feet wide.

|

|

|

| | |

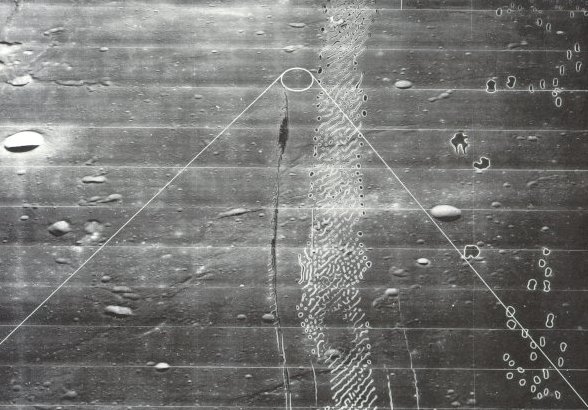

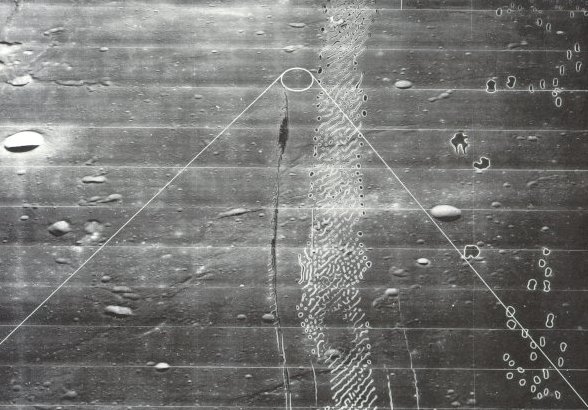

The picture above is an oblique

view of the same area. This Lunar

Orbiter photograph illustrates more

nearly the way it would look to an

astronaut descending to land. The

white lines iridicate the elliptical

target site and the approach boundaries. Processing flaws such as seen

in this picture resulted occasionally

from partial sticking of the moist

bimat film development used

aboard the Orbiter spacecraft.

|

|