Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

AN ADVANCED COMPUTER COMPLEX

As the team was being built, the facilities and equipment were also being

defined, developed, constructed, and brought on line. The Mercury flights were

directed from a control center at Cape Canaveral, Fla. In 1962, the Space Task

Group moved to Houston to form the Manned Spacecraft Center. The construction

of the Mission Control Center in Houston, designed to accomplish the lunar missions,

was started in 1962. Thirty-six months later it was to be used to control Jim McDivitt's

and Ed White's flight in the Gemini IV spacecraft. Its full capability was not used for

Gemini, however, as much work still had to be accomplished. One of the most

advanced computer complexes in the world had to be integrated with a global tracking

network. Tracking and telemetry data had to be relayed from stations in Australia,

Spain, the Canary Islands, Guam, Ascension Island, California, Bermuda, Hawaii,

Tananarive, and Corpus Christi. Tracking ships were built to provide additional

communication coverage in ocean areas. Special Apollo Range and Instrumentation

Aircraft (modified Boeing KC-135 jets) were deployed around the world.

| | |

Resembling a porpoise with its bottle-nosed antenna housing,

this converted KC-135 tanker was one of four Apollo Range

and Instrumentation Aircraft. ARIA supplied voice and telemetry

coverage to the Apollo spacecraft over those parts of the Earth

orbits that were beyond the reach of the ground stations.

|

|

The 85-foot paraboloid at the Honeysuckle

tracking station in Australia is one of the three

primary antennas on which MSFN depends for

tracking at lunar distances. All three are located

alongside similar dishes of the Deep Space Network.

This redundancy increased Apollo mission safety.

|

| | |

The tracking ship Vanguard was

positioned, for Apollo launches, in an

area of the Atlantic Ocean where

there are no island stations. It provided

tracking, telemetry, and voice

coverage during the insertion into

Earth orbit, As many as five tracking

ships were employed on the early

Apollo missions.

|

All this was being done concurrently with the evolution of operational concepts.

During the Mercury and Gemini flight programs, teams of flight controllers at the

remote tracking stations were responsible for certain operational duties somewhat

independent of the main Control Center. The advantages of having one centralized

operations team became more apparent, and for Apollo,

two high-speed 2.4-kilobit-per-second

data lines connected each remote site to the Mission Control Center in

Houston. This permitted the centralization of the flight control team in Houston.

Provisions were also made to tie into the Control Center, through a communications

network, the best engineering talent available at contractor and government facilities.

| | |

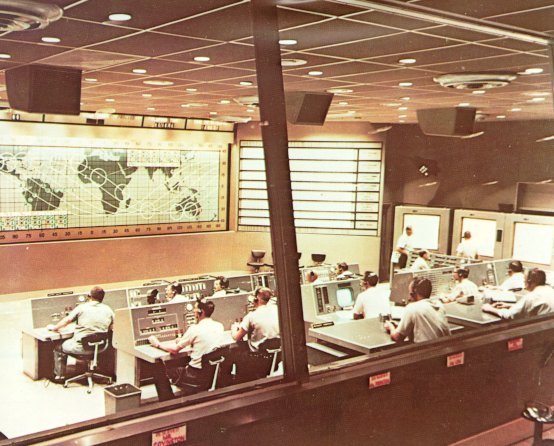

In Mercury days, with a one-man spacecraft in

Earth orbit, this control center was sufficient.

|

|

| |

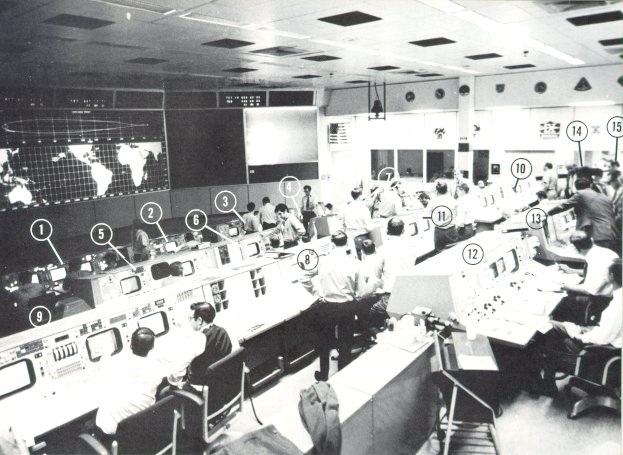

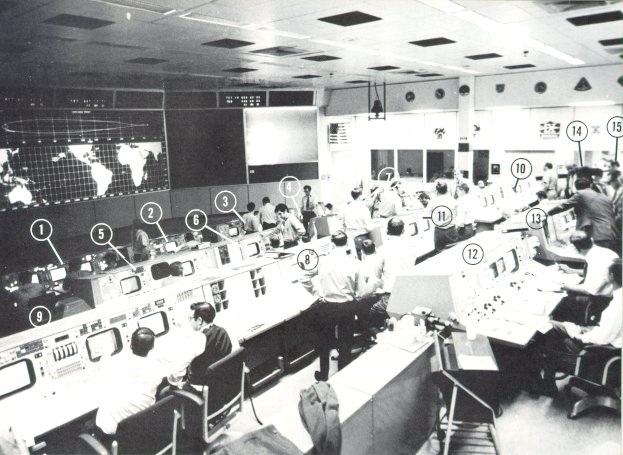

By Apollo, with three men in two spacecraft at lunar

distances, Mission Control had grown.

An array of specialists manned the consoles during an Apollo mission.

Key numbers above identify the locations of flight controllers. 1 was

the Booster Systems Engineer, responsible

for the three Saturn stages. 2 was the Retrofire Officer,

keeping continuous track of abort and return-to-Earth options. 3 was

the Flight Dynamics Officer, in charge of monitoring trajectories

and planning major spacecraft maneuvers; he also managed onboard

propulsion systems. 4 was the Guidance Officer, who watched

over the CSM and LM computers and the abort guidance system. In

the second row, 5 was the Flight Surgeon, keeping an eye on the

condition of the flight crew. At 6 was the Spacecraft Communicator,

an Astronaut and member of the support crew, who sent up the

Flight Director's instructions. (He was usually called CapCom, for

Capsule Communicator, from Mercury days.) 7 concerned CSM and

LM systems, including guidance and navigation hardware; and electrical,

environmental, and communications systems. After Apollo 11, all communications

systems were consolidated as a separate task. On the

next row in the middle was 8, the Flight Director, the team leader. 9

was the Operations and Procedures Officer, who kept the team - in and

out of the Center - working together in an integrated way. 10 was

the Network Controller, who coordinated the worldwide communications

links. 11 was the Flight Activities Officer, who kept track of

flight crew activities in relationship to the mission's time line. 12 was

the Public Affairs Officer who served as the radio and TV voice of

Mission Control. 13 was the Director of Flight Operations; 14 the Mission

Director from NASA Headquarters; and 15 the Department of Defense

representative. During activity on the lunar surface an Experiments

Officer manned the console at 1 to direct scientific activities and relay

word from the science team.

|

As engineers from the Goddard Space Flight Center were intently determining

the requirements for this ground communications network, building and installing

equipment, and laboriously testing and verifying the network's capabilities, engineers

in Houston, led by a young Air Force officer, Pete Clements, and a fine young

engineer, Lynwood Dunseith, were feverishly working to integrate the computer complex

and Control Center displays with the network. The critical parameters and limits

that had to be monitored in flight needed to be defined; the necessary sensors for

measuring the parameters needed to be incorporated in the design of the spacecraft;

and rules for utilizing the measurements needed to be developed. But it was not only

a question of ensuring that the right measurements were made. Spacecraft and subsystem

design also had to have the redundancy and the flexibility needed to overcome

failures and contingencies as they arose. And time was relentlessly marching on. Testing of

the spacecraft revealed new problems, and new techniques and procedures

often had to be developed to avoid potential difticulties in flight. Programs had to be

developed for operating the spacecraft and Control Center computers, and the programs

had to be verified, tested, and incorporated in the computers. The end of the

decade moved closer each day. The complexity of the spacecraft and launch vehicle

was exceeded only by the complexity of a worldwide ground-control system.

|

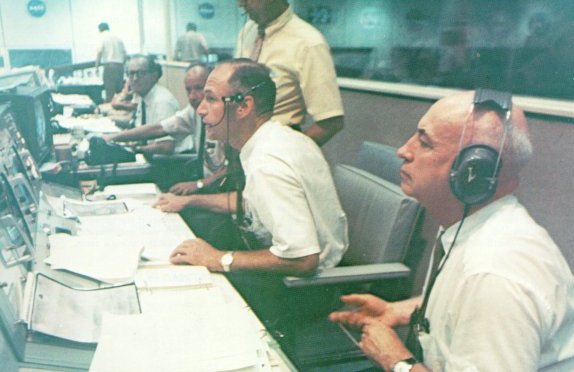

Only minutes before this picture was taken, Jack

Swigert had made the call, "Houston, we've had

a problem." Left to right, Christopher C. Kraft,

Jr., Deputy Director of the Manned Spacecraft

Center; James A. McDivitt, Apollo Spacecraft

Program Manager; and Robert R. Gilruth, Director

of the Manned Spacecraft Center.

|

|

Astronauts assigned to an upcoming mission

took particular interest in following the current

flight from the Mission Control Center. In this

picture, taken during the Apollo 10 mission, Neil

Armstrong (left) and Buzz Aldrin (right) discuss

the lunar orbit activities in progress with astronaut-scientist

Jack Schmitt.

|

Then came January 27, 1967, and the AS-204 fire, a day I'll never forget. I was

at the console in Houston monitoring the test at the Cape, together with a group of

flight controllers. We thought we had considered every eventuality, and now we were

struck down by an event that did not occur in space but happened during a ground

test. There were no excuses that could be offered but, out of the despair of the fire,

there came a rededication to the successful accomplishment of the goal and an

intensified effort on the part of every individual.

The Operations Team had many functions not associated with testing and checking

out the spacecraft and controlling the mission. These functions were nevertheless

essential to success. One was recovery operations. Recovery techniques for the spacecraft

and the crew had to be worked out in conjunction with the Department of

Defense and the U.S. Navy. Bob Thompson organized and led this effort during

Mercury and Gemini. The organizational team he established provided the same excellent

recovery support for Apollo as it had for Mercury and Gemini.

| | |

A long moment of quiet satisfaction in the Mission

Operations Control Room during the Apollo

11 mission, as George Low and Robert Gilruth

look past their consoles toward a television monitor

where they can watch astronauts Armstrong

and Aldrin walking on the Moon.

|

|