Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

CHOOSING THE FIRST MAN ON THE MOON

Once it was fairly certain that Apollo 11 was it, newspaper reporters and some

NASA officials predicted that Aldrin would be the first man to step on the Moon.

The logic was that in Gemini the man in the right-hand seat had done the EVA, and

the early time line drawn up in MSC's lower engineering echelons showed him dismounting

first. But the LM's hatch opened on the opposite side. For Aldrin to get out

first it would have been necessary for one bulky-suited, back-packed astronaut to climb

over another. When that movement was tried, it damaged the LM mockup. "Secondly,

just on a pure protocol basis", said Slayton, "I figured the commander ought to be

the first guy out ... I changed it as soon as I found they had the time line that showed

that. Bob Gilruth approved my decision." Did Armstrong pull his rank, as was widely

assumed? Absolutely not, said Slayton. "I was never asked my opinion", said Armstrong.

"It was fine with me if it was to be Neil", Aldrin wrote, half-convincingly.

Five days before he sent McDivitt and White on that 1965 midnight ride to

Paris, Lyndon B. Johnson had thrown a monkey wrench into the Pentagon's machinery

by jubilantly announcing that he was promoting those astronauts, both Air Force

officers, from major to lieutenant colonel (he didn't bother to find out that both had

only recently made major). The astronauts were naturally delighted.

| | |

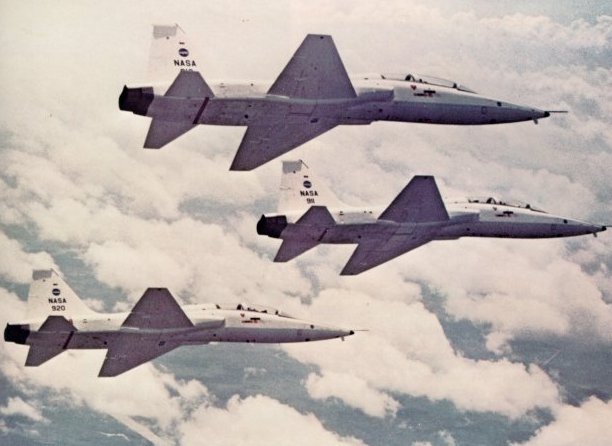

A constant companion to an Astronaut during

his training was the graceful twin-engined T-38,

a two-seat jet that was fine for aerobatics.

T-38's were handy for the incessant travel - to

California, New York, the Cape, and way stations - that

was called for by the policy of

involving astronauts in spacecraft development.

And to men who had in the main been expert

test pilots, the agile T-38 was both a means of

keeping sharp and a resource offering privacy

and pleasure. |

|

Mike Collins, left, lands after an exhilarating

session of aerobatics. The T-38 was useful not

just as a means of keeping piloting skills fine-honed

but also to keep up g-load tolerances

and inner-ear response to weightlessness. Plenty

of flight hours before launch seemed to reduce

the tendency toward nausea during initial exposure

to weightlessness during spaceflight.

|

In justice to Maj. Virgil Grissom USAF and Lt. Comdr. John Young USN, who

had flown Gemini 3 three months earlier, the President accelerated promotions for

them, too, again without saying anything to NASA or the Defense Department. He also

went back and picked up some unpromoted Mercury astronauts. Admiral W. Fred

Boone, NASA's liaison officer to the Pentagon, noting "some dissatisfaction both

among the astronaut community and in the Pentagon", undertook a study. Wrote

Boone: "We agreed it would be preferable that meritorious promotions be awarded

in accordance with established policy rather than on a 'spur of the moment' basis."

The upshot was a policy, approved by the President, providing that each military

astronaut be promoted after his first successful flight, but not beyond colonel USAF

or captain USN. Civilians would be rewarded by step increase in civil service grade.

Only one promotion to any individual.

That policy came unstuck on Apollo 12, flown by three Navy commanders,

Pete Conrad, Dick Gordon, and Alan Bean. Conrad and Bean, having been upped

from lieutenant commander to commander after their Gemini 11 flight, were ineligible

for another promotion. Rookie Bean was. But should Bean be promoted over the

heads of his seniors? Hang the policy, said President Nixon, promoting all three.

| | |

A parabolic flight path in a jet transport could create

up to 30 seconds of zero gravity, enough to practice

exit through a spacecraft hatch (above). Two earthbound

simulations of reduced or zero gravity are shown

at right and below. Wearing pressure suits carefully

weighted to neutral buoyancy, astronauts in a big water

tank learn the techniques needed to work effectively in

space. Below, ingenious slings are supported by wires

running to a trolley high above. The angled panels on

which the man walks or runs are offset just enough from

directly under the trolley to simulate the sixth of Earth

gravity that prevails on the Moon.

|

Of all the amenities accruing to astronauts, the hard cash came from "the Life

contract". Between 1959 and 1963 Life magazine paid the Seven Original astronauts

a total of $500,000 for "personal" stories - concerning themselves and their

families - as opposed to "official" accounts of their astronautical

duties. This arrangement

increased the astronauts' military income by about 200 percent. It also simplified NASA

public relations, since the famous young men's bylines would be concentrated in one

place and the contract called for NASA approval of whatever they said.

There were drawbacks. The rest of the press took a sour view of what it considered

public property being put up for exclusive sale (the dividing line between

"personal" and "official" was wafer-thin). Since the same ghostwriters put their

stories in print, the astronauts (and their families) all seemed shaped in the same

mold, utterly homogenized for the greater glory of home, motherhood, and the space

program. "To read it was to believe we were the most simon-pure guys there had

ever been", wrote Buzz Aldrin in Return to Earth. "The contract almost guaranteed

peaches and cream, full-color spreads glittering with harmless inanities", was the way

Mike Collins's book had it.

|