Chapter 5: Craters (5/6)

|

[152] |

|

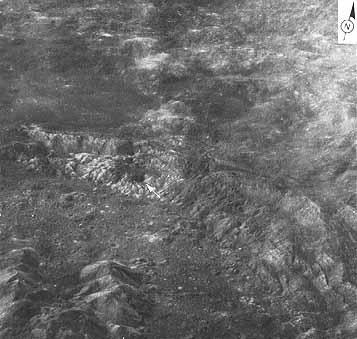

FIGURE 152 [above].-A close look at the western part of the floor of the crater King reveals many similarities to the floors of other fresh craters such as Copernicus or Tycho. The crater wall rises steeply along the left. Cracked and corrugated lavalike material occupies low areas between hills and knobs on the floor. Some cracks extend across hills, suggesting that those hills are completely covered by the lavalike material. Rocky outcrops on other hills (some examples are identified by arrows) show that they are made of hard rock.-K.A.H.

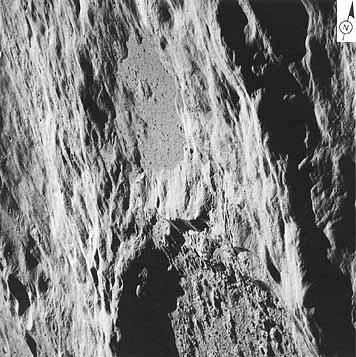

[153] FIGURE 153 [below].-This greatly enlarged part of a panoramic camera photograph shows a small area in the eastern part of the floor of the crater King. The large mass in the left part is one example of the many domed structures that occur in the floor of King. It is trisected by depressions in the shape of an inverted "Y" representing three faults; one trends north-south (1), another northeast-southwest (2), and the third northwest-southeast (3). In the area of the fractures and the resulting grabens and depressions, there are numerous blocks indicating that tectonic movement has occurred relatively recently. The northwest-southeast trending fault continues across the level floor to the lower-right corner of the picture. An intricate pattern of finer fractures trending in many directions is also present in the level part of the floor. The partly arcuate nature of the fractures suggests that some may represent cooling cracks.-F.E.-B.

|

[154] FIGURE 154 [left].-This oblique view looking north across the northern part of the crater King was taken by the Apollo 10 crew. The very dark patch on the northern wall of King near the center of the photograph was first observed on that mission and has since been the subject of detailed visual study and orbital photography. The rocks of this dark patch are the darkest material yet recognized in the far-side highlands and are surrounded by brighter material. Two bands of this brighter material extend northward for approximately 30 km beyond the crater. In the near field, at the lower left, is the northern half of the Y-shaped central peak of King. A dark pool of relatively smooth material is visible just beyond the alternating bands of dark and light rocks on the north rim of the crater. The alinement of the arms of the central peak, the bands of dark and white rocks, and the concentrations of blocky material on the central peak complex and on the crater floor all suggest that when this crater was formed, a preexisting linear body was encountered and partly exhumed.-F.E.-B.

|

|

| |

|

FIGURE 155 [left].-The Apollo 16 astronauts captured this spectacular view of the large dark "pool" on the north flank of the crater King (left) as they approached from the east. The pool (also known as a lake, pond, or playa) is in an old crater swamped by King ejecta. The maximum width of the pool is about 21 km. The peculiar dark material that forms the large pool and also coats adjacent hills was first discovered on Apollo 10, and was later seen again from Apollo 14. The most exciting part of the discovery had to wait until the mapping and panoramic cameras of Apollo 16 showed that this material contains some of the freshest and most spectacular flow structures on the Moon. These structures, some of which are seen in the following figures, show that the material behaved like lava. The material is very similar in appearance to that filling parts of the floor of King. -K.A.H.

|

|

[155] FIGURE 156 [left].-Here the Apollo 16 panoramic camera views the same large pool of dark material. For orientation, the hill identified by an arrow is the "island" near the center of the pool in Figure 155. In the highlands surrounding the main pool are many small pools. Their surfaces merge with a veneer of similar material on adjacent slopes, as if most of the rim of the old crater had once been coated by a fluid rock that partly drained off to accumulate in depressions. Cracks (C), flow channels (FC) near the middle of the picture, and numerous wrinkles show that the material flowed like lava toward the main large pool. Whether the lavalike material is volcanic lava or rock melted by the impact is in vigorous debate. The material is restricted to the north rim of King where ejecta is also most concentrated. If the ejecta is concentrated on the north because north was downrange from an obliquely impacting body, that condition would support an impact origin for the dark material.-K.A.H.

|

|

| |

|

FIGURE 157 [left].-A schematic map based on figure 155 shows some of the geologic relationships. The solid line marks the rim crest of the crater King and the stipple pattern delineates the many pools of smooth dark material. Dashed lines represent lineaments that probably are the surface expressions of faults. Arrows indicate the directions of flow of the molten or partially molten material from higher to lower levels; most finally accumulating in the large pool in the center. A scarp whose origin is not fully understood, but which may possibly be the result of splashing of the molten material from the impact site onto a slope is indicated by S.-F.E.-B. |

AS16-5000 (P) |

[156] FIGURE 158 [left].-This enlargement of figure 156 shows details in the lavalike materials. The flow features are so young that younger cratering events have not obliterated them. The prominent leveed flow channel in the center of the picture indicates that the material flowed downhill in the direction of the arrows toward the large pool. Like terrestrial volcanic lava, the material is locally compressed into festoonlike corrugations that arch "downstream." In other areas, especially where draped over hills, the material has been stretched and dense patterns of cracks have formed. A linear texture trends northwestward across much of the area shown, but is mostly clearly visible in the lower right corner. It is the expression of King's ejecta blanket underneath the veneer of the lavalike material. If the lavalike material is impact melt, it must have coated the ejecta and drained downhill after the ejecta flowed radially away from King.-K.A.H.

|

|

| |

|

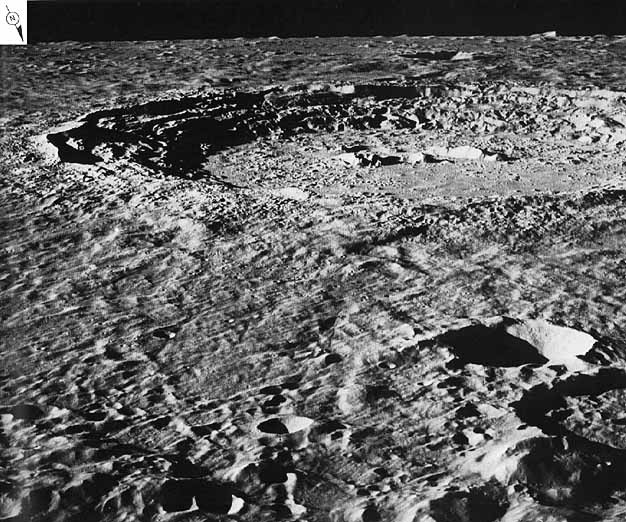

FIGURE 159 [left].-The ejecta blanket of King fills this entire scene except for the crater itself and a few small superposed craters. The ejecta coats larger craters, such as the two on the right edge, and completely swamps smaller ones. A large lobe in the ejecta at lower center has been compared (El-Baz, 1972b) to an apparent landslide at Tsiolkovsky (figs. 175 and 176). Close inspection of the surface of the ejecta blanket reveals fine lineations that are concentric near the rim crest and radial further out. Where slopes are encountered, the radial lineations veer from their normal direction to swerve down the slopes.-K.A.H.

|

|

[157] |

|

FIGURE 160 [above].-An enlarged view of the area outlined in figure 159 shows the concentric dunelike lineations more clearly. A few of the lineations veer from concentric to radial in orientation. The outward change on a broader scale from concentric to radial patterns also occurs at other fresh craters, and probably records changing conditions of flow as the ejecta was transported outward at high velocity. On the crater wall, numerous fine fractures parallel the terraced slump blocks, much as in landslides on Earth.-K.A.H.

|

[158] |

|

FIGURE 161 [above].- The lobate scarps in the foreground are a lunar feature seen as Apollo 16 flew over the margins of King's ejecta blanket. This view looks away from King and is centered about 50 km from its rim crest. The lobes appear to border thick flows or slide masses of King ejecta. Beyond the lobes in the upper left part of the picture the ejecta is thin or absent.- K.A.H.

|

[159] FIGURE 162 [left].-Here is an enlarged vertical view of more flow lobes immediately south of those in figure 161. Fine lineations radial to King are prominent in the ejecta blanket behind (southeast of) the lobate fronts. The term "deceleration lobe" has been applied because the lobes occur only where the ejecta slowed down and came to rest on slopes that face toward King. They resemble terrestrial rock avalanche deposits that came to rest after climbing a small slope. Some lobes overlap each other outward like shingles. The sketch shows what would probably be seen in a cutaway view. The arrow shows the direction of movement of the ejecta over the old landscape.-K.A.H.

|

|

[160] |

|

FIGURE 163 [above].-Here the panoramic camera sees the edge of King's ejecta blanket 75 km northeast of the crater. The bright slope along the left side of the photo faces both the Sun and King. It apparently acted as a barrier for the ejecta surging outward from King, for there are small deceleration lobes on the slopes. Most of the plateau east of the slope is pocked by small craters that were not covered by the ejecta blanket. However, a belt of linear dunelike features radial to King crosses part of the plateau from lower left to upper right. Careful inspection shows that the lineations are downrange from a cluster of small irregular craters (arrow) at the left edge of the plateau. These are part of a field of secondary impact craters that completely surround King's ejecta blanket. Debris thrown out on low-trajectory paths from King made the secondary craters and apparently splashed debris downrange. Closer to King, the continuous ejecta blanket is lineated in the same way as is the secondary ejecta. Perhaps much of the continuous ejecta blanket is also formed of material splashed out by secondary impacts.-K.A.H.

[161] FIGURE 164 [below].-The large crater Copernicus has served as a type example of lunar impact craters since the classic analysis was made by E. M. Shoemaker (1962). Bright rays of ejecta radiate outward from Copernicus across a large part of the Moon's near side. Material from one of the rays may have been sampled at the Apollo 12 landing site, 370 km south of the center of the crater. This photograph shows how the crater appeared from the Apollo 17 spacecraft looking southward over the Montes Carpatus (Carpathian Mountains). Notice that the rim deposits immediately adjacent to the crater have a very crisp, blocky appearance in contrast to the softer appearance of the rest of the ejecta blanket. This crisp zone is also found on many other craters and suggests the ejecta here was swept clean by some erosion process late in the cratering event. The terraced slumps on the crater wall appear like giant stair steps leading to the floor, 3 to 4 km below the rim. The 1-km-high central peaks were made famous in 1966 by a "picture of the century" view looking into the crater from the south by Lunar Orbiter 2. Now Apollo has given us scores of even more spectacular photographs.-K.A.H.

|

[162] |

|

FIGURE 165 [above].-Aristarchus is a large crater on the edge of a plateau within northern Oceanus Procellarum. In this scene the crater is viewed obliquely from the north. One of the brightest and youngest craters of its size on the near side of the Moon, Aristarchus is believed to be younger even than Copernicus. The general appearance of Aristarchus and of parts of the plateau around it led Alfred Worden, the Apollo 15 CMP, to describe this part of the Moon as "... probably the most volcanic area that I've seen anywhere on the surface." For many years before the Apollo missions, Earth-based viewers had reported telescopic sightings of transient events centered on Aristarchus. These brief, subtle changes in color or in sharpness of appearance have been suggested as evidence for volcanic activity or the venting of gases from the lunar interior. The sightings are controversial, but Aristarchus remains a center of interest. -M.C.M.

About 39 km in diameter, Aristarchus is on the borderline between medium-sized and large- sized craters. We have included it among the large craters because its welldeveloped concentric terraces are characteristic of most large craters that have not been too severely degraded. Its terraced walls, as well as its arcuate range of central peaks, are particularly well shown in this view. The walls and parts of the crater floor are extremely rough and cracked, a characteristic feature of other young impact craters of this size range, such as Tycho and Copernicus. The rough deposits in the floor are probably made up largely of shockmelted material formed at the time of the impact. The inner, rougher portions of the rim show a series of channels, lobate flows, and smooth puddlelike deposits that may represent shock-melted material deposited on the crater rim. The outer, smoother portions show the rhomboidal pattern characteristic of crater ejecta blankets.-J.W.H.

[163] FIGURE 166 [below].- Theophilus is a relatively young crater similar in size but slightly older than Copernicus (fig.164). It lies on the eastern edge of the Kant plateau, an elevated area in the Central Highlands along the northwestern margin of Mare Nectaris. Part of Nectaris is visible as the smooth. dark area near the horizon at the left edge. Like Copernicus and Aristarchus, Theophilus has ruggedly terraced walls and a complex central peak protruding through a level floor. Smooth-surfaced material is present in "pools" at various levels on the terraces, on parts of the crater floor, and on the ejecta that blanket the near (north) side of the crater. As one alternative, the pools may have been emplaced as fluid lava. The pooled material and the prominent central peak complex of Theophilus are shown in more detail in figures 167 and 168.- M.C.M.

| Next |