Chapter 3

Routes to Space Flight

[61] By the mid-1950s, the idea of manned space flight emerged from the realm of fantasy to become a topic of serious technical discussion. Frederick C. Durant III, President of the International Astronautical Federation (IAF), told the delegates gathered in 1954 at Innsbruck, Austria, that "the feasibility of space flight is no longer a topic for academic debate, but a matter of time, money and a program."1 To illustrate his point, Durant showed the Walt Disney Productions motion picture Man in Space during the August 1955 Sixth Congress of the IAF in Copenhagen.

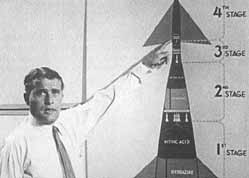

After an introductory discussion on the evolution of rockets, three American proponents of "man in space" addressed different aspects of manned space flight. Willy Ley described the prospects for utilizing rockets in space travel and the steps required to build a space station that could orbit 1,730 kilometers above the earth. Through the medium of an animated cartoon character, "Homo Sapiens Extra-Terrestrialis," Heinz Haber explained some of the questions raised by "space medicine," illustrating the physiological hazards - acceleration loads, weightlessness, cosmic radiation, meteorites - that the first space travelers would encounter, Finally, Wernher von Braun closed the film with a discussion of his conceptual design for a 55-meter tall, 1,280- metric ton, four-stage interplanetary rocket that could carry a crew of six into the cosmos.* 2 The IAF delegates were enthusiastic about this 33-minute movie, especially in the light of President Eisenhower's earlier announcement that the United States would launch artificial satellites during the International Geophysical Year.

Among the viewers of Man in Space were Leonid Ivanovich Sedov and Kyril Feodorovich Ogorodnikov, the first Soviets to attend an IAF Congress. They spoke with Durant about borrowing the film for use in the Soviet Union, saying it would be "very good to have here a copy of Walt Disney's [62] excellent film for private demonstration."3 It is likely that the Soviets viewed Man in Space as proof of growing American interest in solving the basic problems associated with manned space flight. Sedov and Ogorodnikov wanted to use the Disney picture to promote their own nation's efforts in rocketry and space research. To Soviet space enthusiasts, the movie was at once an encouragement and a warning.Seven years after that Copenhagen meeting, both the U.S.S.R. and the U.S. orbited and returned their first space pilots. Vostok and Mercury were possible within such a short span of time because engineers and scientists had amassed a wealth of basic engineering and scientific data directly applicable to the questions posed by manned space flight. In those early years, much of the work was duplicative, as security restrictions forced Soviet and American researchers to repeat the same fundamental investigations; but if the competitive environment was wasteful, it also spurred the development of space flight technology. Seemingly, man would have crossed the barriers of the space frontier without the element of international competition, but it was precisely that element that did give rise to the space program - and made...

[63] ...funds available. Fantasy yielded to reality; and that reality was the orbiting hardware.

* In 1955, Ley was a

writer of factual science publications centering on rocketry and

space exploration; Haber was a member of the physics department at

UCLA, after having worked five years as a research scientist with the

Air Force School of Aviation Medicine; and von Braun was Chief of the

Guided Missile Development Division at the Army's Redstone

Arsenal.

1. Frederick C. Durant, III, "Space Flight Needs Only Money, Time," Aviation Week, 27 Sept. 1954, p. 46. On 14 July 1952, the executive committee of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics passed a resolution that "NACA devote modest efforts to problems of unmanned and manned flights at altitudes from 50 miles to infinity and at speeds from Mach 10 to escape from the earths gravity." NACA to High Speed Flight Research Station, "Discussion of Report on Problems of High Speed, High Altitude Flight, and Consideration of Possible Changes to the X-2 Airplane to Extend Its Speed and Altitude Range," 30 July 1953, which contains the NACA directive.

2. Joe Reddy, memos for record, "Man in Space: Production Story," and "#20 Disneyland-TV Man in Space," Walt Disney Productions synopsis and background, 1955. Von Braun, Haber, and Ley had long been advocates of space flight, and as early as 1952 they had contributed articles to a Collier's symposium entitled "Man will conquer space soon." The articles included Wernher von Braun, "Crossing the Last Frontier," pp. 24-29 and 72-74; Willy Ley, "A Station in Space," pp. 30-31; Fred L. Whipple, "The Heavens Open," pp. 32-33; Joseph Kaplan, "This Side of Infinity," p. 34; Heinz Haber, "Can We Survive in Space," pp. 35 and 65-67; and Oscar Schachter, "Who Owns the Universe?" pp. 36 and 70-71, Collier's, 22 Mar. 1952.

3. Kyril Feodorovich

Ogorodnikov to Durant, 23 Sept. 1955; Leonid Ivanovich Sedov to

Durant, 24 Sept. 1955; Durant, "Impressions of the Sixth

Astronautical Congress," Jet

Propulsion 25 (Dec. 1955): 738; and

interview (via telephone), Durant-Ezell, 13 Dec. 1974. Based upon his

conversations with the two Soviet scientists, Durant conjectured that

the then anonymous Soviet "Chief Designer of Spacecraft," S. P.

Korolev, was to be the intermediary who would present Man in Space to the

Soviet political and technical leadership.

Next