Vostok and Mercury: First Flights

into Space

[73] The years 1958-1961 were busy ones in both the United States and the Soviet Union for the development of manned space vehicles.* According to Konstantin Petrovich Feoktistov, the details for mockups and breadboard models of Vostok were worked out and then built during 1959. Final developmental work on the "carrier rocket" was being conducted simultaneously at the launch site.23 By 15 May 1960, the Soviets had progressed sufficiently with the development of their spacecraft and the adaptation of their ICBM boosters as launch vehicles to commence a series of five unmanned test flights. These Vostok precursor flights, Korabl Sputnik I through V, were designed to collect additional data on the effects of space environment (especially solar radiation) on biological specimens and to test the spacecraft systems. The flights included no unforeseen physiological problems associated with manned space missions, but the first and third spaceships did encounter trouble upon reentry. The problem centered on the proper orientation for retroengine firing, a difficulty that was worked out by the time the fourth and fifth test missions were flown in March 1961. Feoktistov indicated that a round of technical discussions led to major changes in the spacecraft during September-December 1960. "In late 1960-early 1961 the revised technical documentation was used for the manufacture of the spaceships." The Soviets were ready to begin manned space flight operations.24

The rationale of the six Vostok flights has been summarized by design engineer and cosmonaut Feoktistov. Yuri Gagarin's flight on 12 April 1961 was a single-orbit checkout of the spacecraft systems. Rather than the ballistic shots used at first by the Americans, the Soviets preferred an orbital mission to collect additional data on weightlessness, a topic of considerable concern to Soviet flight surgeons. Indeed, for the second mission, flown by Gherman Titov on 6 August 1961, the medical specialists had urged that the duration be held to just two or three orbits so they could judge the effects of zero gravity, but the designers and Titov wanted to go for a day-long mission, a goal that coincided with political considerations as well. Feoktistov later hinted that the one year hiatus in manned flight following Vostok II may have been related to the motion sickness experienced by Titov. Andriyan Grigoryevich Nikolayev and Pavel Romanovich Popovich in Vostok III...

[74]

....and IV completed their dual mission in August 1962. Though they did not actually rendezvous, they appear to have been within 5 kilometers of each other, thus giving the Soviet trajectory specialists an opportunity to study the problem of rendezvous and to track two spacecraft simultaneously. In June 1963, Valeriy Fedorovich Bykovsky's flight aboard Vostok V lasted nearly five days, and during the last three days he was accompanied in orbit by Vostok VI, piloted by Valentina Vladimorovna Tereshkova, the only woman to fly in space to date. Vostok was the "necessary foundation for . . . further development of manned space vehicles in the Soviet Union."25

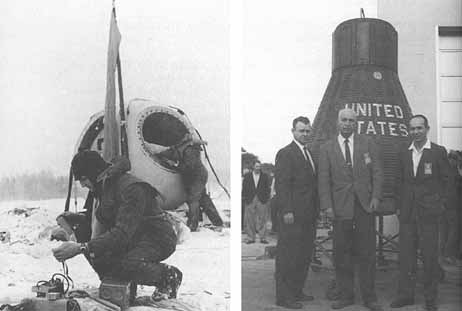

While the Soviet cosmonauts were monopolizing world headlines, work on Project Mercury continued. NASA had embarked upon a step-by-step [75] program of spacecraft and booster qualification trials in 1959. The test program, divided into two parts, sought first to qualify the Redstone and Atlas missiles as launch vehicles for manned spacecraft, and second to "man rate" the Mercury spacecraft itself. The Mercury-Redstone phase of the program covered a 31-month period, during which six missions were flown. The results were mixed. On the very first launch attempt (MR-1), early separation of an electrical ground line to the booster aborted the mission. On the second flight (MR-1A), all systems worked satisfactorily, but problems again appeared in the primate "Ham" mission (MR-2), when over-acceleration caused a higher trajectory and longer downrange travel than had been anticipated. As a consequence, an extra flight was scheduled before a manned launch was attempted. Then on 5 May 1961, less than a month after the Gagarin mission, Alan Shepard became the first American in space, flying a suborbital trajectory in his spacecraft Freedom 7. Gus Grissom in Liberty Bell 7 made the second suborbital flight on 21 July. The data gathered from these two successful missions justified canceling the remaining Mercury-Redstone flights.

Then came the step to orbital flight for which the Atlas missile had been selected as the launch vehicle. When the program was approved in October 1958, no other booster could have been chosen if the objectives of the program were to be accomplished in a reasonable length of time. So, as had the Soviets, the Americans decided to "man rate" an intercontinental ballistic missile. The 57-month flight phase for Atlas began with the launch of the Big Joe Atlas with a boilerplate model of the Mercury spacecraft on 9 September 1959. The first production spacecraft mounted on an Atlas launch vehicle (MA-1) was launched on 29 July 1960. After about 60 seconds, launch vehicle and adapter failed structurally. Because no spacecraft escape system was used, the spacecraft was destroyed upon impact. Following...

[76] ...an intensive seven-month investigation, modifications were introduced to stiffen the adapter between the launch vehicle and the spacecraft and to otherwise improve the structural integrity of the entire upper part of the Atlas. An interim version of the alteration was used without difficulty on the flight of MA-2, while the final version was not tested until the unmanned orbital flight of MA-4 on 13 September 1961. More than two months later on 29 November, Enos, a trained chimpanzee, was launched on a planned three-orbit mission. During the flight of MA-5, the attitude control system performed abnormally, and ground control brought the spacecraft down after two orbits. The problem, as demonstrated on later flights, could have been corrected by an astronaut, thus confirming the American judgment favoring manual overrides of automatic control systems.

After a series of frustrating delays caused by unfavorable weather and fuel leaks, John Glenn became the first American to orbit the earth. His flight was followed by a three-orbit mission flown by M. Scott Carpenter, in which the only problem was an attitude misalignment at the time of retrofire, causing a 402-kilometer landing overshoot. As the next step toward a day-long mission, Walter M. Schirra piloted a six-orbit mission on 3 October 1962. By drifting in flight, he conserved critical fuel and demonstrated the feasibility of longer duration missions. The 34-plus-hour mission of L. Gordon Cooper on 15-16 May 1963 was Project Mercury's last flight.26

Mercury and Vostok demonstrated the feasibility of placing a human being in orbit, observing his reactions to the space environment, and returning him safely to earth at a known point. While the Soviet designers assigned limited tasks to their cosmonauts, NASA went one step beyond to demonstrate that man could function as "an invaluable part of the space flight systems as pilot, engineer and experimenter." The next stage was the development of more flexible and multi-place spacecraft for the conduct of more intricate missions - the era of Gemini and Voskhod.

* Appendix B lists the major Soviet and American developmental (unmanned) and manned flights.

23. Feoktistov, "Razvitie sovetskikh pilotruemuikh kosmicheskikh korablei," p. 37; Astashenkov, Academician S. P. Korolev, Biography, pp. 187-190; Riabchikov, Russians in Space, p. 155; and Vladimirov, The Russian Space Bluff, p. 89. Vladimirov indicates that one of the more serious problems encountered by the Soviet team was the heart attack suffered by Korolev on 3 Dec. 1960.

24. Feoktistov, "Razvitie sovetskikh pilotruemuikh kosmicheskikh korablei," p. 37.

26. Swenson, Grimwood,

and Alexander,

This New Ocean, pp. 341-511, summarize

the operational phase of Project Mercury.

Next