Testing Hardware

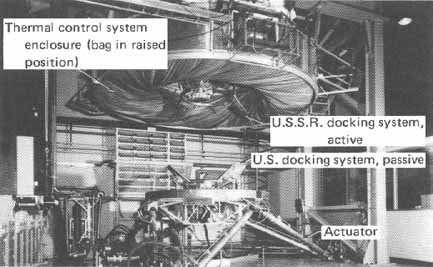

While the crews were beginning to study spacecraft systems related to the mission, progress continued in readying the hardware they would ultimately fly. From 16 September to 24 December, Working Group 3 conducted tests with the developmental version of the docking system. This first piece of full scale equipment had been built from the engineering drawings as they had been perfected to that point, and while it was still far from being a flight-ready item, this version of the docking system was subjected to careful analytical and operational scrutiny on the computer-driven Dynamic Docking System Simulator (DDTS). Housed in the JSC Structures and Mechanics Laboratory, the DDTS was capable of duplicating the most severe impacts and thermal conditions that could be anticipated when the docking systems were brought together in space. The test program consisted of 236 test runs, which subjected the American and Soviet gear to [258] temperature ranges of -50° to 70° centigrade and to the active and passive modes.

A team of eight Soviet specialists, led by V. S. Syromyatnikov and Ye. G. Bobrov, worked with the regulars of Group 3, plus the test personnel in George E. Griffith's Structural Test Branch, computer people from the Spacecraft Systems Laboratory, and contractor employees who operated the DDTS. The extremely complex facility had been completed just before the Soviet team arrived, and some initial problems were encountered with the simulator, taking time away from the scheduled testing. According to Bob White, who had overall responsibility for the tests, "this caused team members from both countries to dedicate many extra hours at night and on weekends for make-up testing. Everyone worked admirably without complaining and a strong sense of mutual respect became discernible." Although the schedule was very demanding, one weekend was set aside for a private tour of the State Capitol and the Governor's office in Austin, as well as the engineering college and the Lyndon B. Johnson Library at the University of Texas.

During this fourteen-week evaluation process, a number of minor changes were incorporated into the design. But since there were no failures or major problems with either the U.S. or U.S.S.R. docking system, manufacture of the flight hardware could proceed on schedule. While the flight and backup systems would be subjected to a much more rigorous quality assurance program while being manufactured, the dynamic docking tests of the prototype system had been an essential step in defining the characteristics of that production equipment. With all the extra work completed, the Soviets departed on Christmas day, and many of the Americans, accompanied by their families, traveled to the Houston Intercontinental Airport to wish their friends a safe journey.32

During mid-January joint meetings held in Houston, the Soviets participated in tests of the docking module environmental control systems (ECS). As in the case of the development of the docking system, the breadboard version of the docking module ECS was designed to check out...

Interior view of environmental control system breadboard. Test specialist Tom Wilks prepares for test of the system under simulated space conditions.

[259] the operational and functional characteristics of the prototype equipment prior to fabrication of flight hardware. Although the test hardware was different in appearance from the final docking module and although the Apollo and Soyuz transfer tunnels were simulated by two pressure vessels, the ECS test hardware functioned like the real thing. The ECS breadboard was placed in the Life Systems Laboratory vacuum chamber, a horizontal cylinder 2.44 meters in diameter and 5.8 meters long. The chamber, divided by a bulkhead into two compartments, consisted of a manlock passageway and a test chamber to house the test article. Like most test facilities at JSC, the vacuum chamber was equipped with a closed circuit television system, which permitted remote viewing of the manlock compartment, the breadboard ECS, and the test chamber interior, and also equipped with a multi-channel intercommunications system, which linked all test personnel.

The joint tests, which ran from 16-23 January, were divided into two major categories - manned simulated mission tests and unmanned functional performance tests. During the manned tests conducted on 16 January, the performance of the system was demonstrated by simulating three transfers, during which the docking module environment reflected extreme situations that were not likely to occur during flight. By testing extreme cases, the suitability of the systems was scrutinized and the acceptability of manned operation under low or high oxygen pressures was determined. Later, unmanned functional performance testing was conducted to establish the leakage rates for the test chamber and to verify the major failure protection systems included in the docking module ECS. Results from these exercises indicated that the environmental control system met all the design specifications and that the transfer procedures were adequate in both normal and emergency situations. In addition, all of the safety equipment, such as the overpressure valve, performed successfully.33

Next came familiarization training for the American ASTP crews with this hardware. After the completion of the last Skylab visit on 8 February, all of the crewmembers were given briefings on the docking module systems. On 25 February, they participated in a two-hour walk-through of the ECS...

[260] ....breadboard and test setup. The following day, after a four-hour Skylab debriefing in which all ten ASTP crewmen were involved, Brand and Evans took the first turn in the vacuum chamber to learn the ECS equipment and to practice transfer. Stafford and Slayton went through the same four-hour experience the next day, as did Bean and Lousma on 5 March. The crews were also increasing the number of training hours spent in the command module procedures simulator and command module simulator. And if that were not enough, they had met on the 4th with their new Russian instructors and had begun a new series of intensive lessons.34

Slayton and Stafford had not resumed their language studies after their last return from Star City, and the other crewmembers needed to begin learning Russian. During the November 1973 training sessions in the Soviet Union, the U.S. astronauts had discovered that the cosmonauts had made significant progress in their English studies. When Stafford asked Leonov how they had made such advances, he told the Americans that each member of the Soviet prime crew had his own individual instructors. They were studying language six to eight hours a day. Stafford cabled Washington through the American Embassy in Moscow and requested that the State Department's Foreign Service Institute provide the astronauts with two full-time Russian instructors starting early January. Stafford later told Chris Kraft that the American crew was going to look bad if its members were unable to communicate satisfactorily with their Soviet counterparts. They must get some full-time language training.35

Given the need for additional instruction and the desire to keep abreast of the progress being made by the Soviets, Nick Timacheff was authorized to locate professional teachers who could work with the astronauts. Timacheff screened a number of applicants during the post-Christmas convention of Slavic language professionals in Chicago. Four teachers were selected for their knowledge of contemporary vernacular Russian as opposed to the language as spoken by diplomats. Anatole A. Forostenko, Vasil Kiostun, James D. Flannery, and Nina N. Horner would learn as they taught, since they would have to teach their students the Russian equivalents of NASA's aerospace jargon. While Nina Horner concentrated on lengthy hours of classroom instruction, Forostenko, Kostun, and Flannery accompanied the astronauts on many trips and worked out with them in the gym in an effort to keep them thinking Russian - even when they were playing handball or lifting weights. Starting on 4 March, the prime and backup crewmembers received 3 or more hours of language instruction daily, five days a week. In their spare time, if they were not flying T-38s to keep their reactions sharp, they had cassette tape recorders by their sides to keep their ears sharp.

While the crewmembers studied, Working Group 5 specialists led by Walt Guy went to Moscow to observe testing of the modified Soyuz life [261] support system. American technicians visited a Red Air Force base about 6 kilometers from Star City where the Soviets had their vacuum test chambers. The main test chamber used for the Soyuz tests was composed of a horizontal manlock and a vertical cylinder that was sufficiently large to hold a stacked descent vehicle, orbital module, and docking module simulator. Guy noted the similarities and differences between this test facility and the one in Houston, a major difference being the lack of communications headsets among the test personnel. He commended, "The close proximity of the test crew to each other and the exceptionally quiet test environment . . . made the public address system quite acceptable."

Among the systems evaluated during the tests were those for lowering and raising the Soyuz cabin pressure to determine the effect that transferring men from one spacecraft to another had on the gas composition under normal and abnormal conditions. Guy, Group 5's American chairman, reported later that he came away from the tests with no doubts that the Soviet ECS would work satisfactorily. He had been somewhat concerned about the basic uncontrollability of the chemical bed oxygen system, but after prolonged simulated transfers into the docking module mockup followed by flushing all the docking module gases into Soyuz, the Soviet ECS proved capable of removing the carbon dioxide and other effluents from the atmosphere. At the Americans' request, the trial runs involving four men were longer than the transfers planned for the actual mission; therefore, this was an excellent evaluation of its capabilities. After working with the Soviets in their laboratory, the U.S. team grew confident that there would be no problems with the U.S.S.R. equipment. This was exactly why Glynn Lunney had wanted his men to participate in such activities.36

32. Interview, Robert D. White-Ezell, 30 Sept. 1975; "Apollo Soyuz Test Project, Results of Apollo Soyuz Docking Systems Development Tests," IED 50013, 25 Dec. 1973; NASA, MSC, "E&D Weekly Activity Report," 9-15 Jan. 1974; and White to James M. Grimwood, memo, "Comments on E. C. Ezell's Draft Manuscript of the ASTP History," 6 Jan. 1976.

33. "U.S.A. Docking Module Environmental Control System Breadboard Testing Quick-Look Report," in "Minutes, Working Group 5," 14-25 Jan. 1974.

34. Data given by Brzezinski, 23 Sept. 1975; and interview (via telephone), Walter W. Guy-Ezell, 1 Oct. 1975.

35. Interview, Thomas P. Stafford-Ezell, 6 Apr. 1976.

36. "Integrated Testing

of the Soyuz Life Support System," 11-22 Mar. 1974; "Apollo Soyuz

Test Project, Minutes, Working Group 5," 11-22 Mar. 1974; and

interview (via telephone), Guy- Ezell, 1 Oct. 1975.

Next