Epilogue

[351] While the American ASTP crew toured the Soviet Union and the United States with their Soviet counterparts, major changes were occurring at NASA Headquarters and the Johnson Space Center. In October, the interior walls of the Apollo Program Office in Houston were quite literally moved around to create the Space Shuttle Payload Integration and Development Office. Glynn Lunney, who on the last day of Apollo's flight had been put in charge of managing the Space Shuttle cargoes, had told Boris Artemov, Bushuyev's interpreter, during a telecon on 29 October, "Don't mind the banging, Boris, they're just tearing down the building." Shifting walls were indicative of the changes sweeping the halls at Johnson Space Center (JSC).1

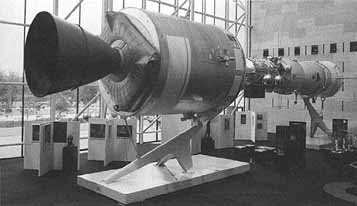

With the splashdown of Apollo, a major chapter in the history of NASA had come to a close. All three generations of American spacecraft - Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo - had been single-flight vehicles. In these essentially experimental craft, the NASA team had mastered the problems of orbital and cislunar flight. Knowing that truly economical space flight would be possible only when the same spacecraft could be flown many times, NASA had begun the search for a reusable vehicle in the late 1960s. The Space Shuttle grew out of that quest. Consisting of three major elements - an orbiter, an external fuel tank, and solid-rocket, strap-on boosters - Shuttle was designed for a crew of four and up to six payload specialists. With a payload bay 18 meters in length by 4.5 meters in diameter, Shuttle would have the capacity to carry a 30,000-kilogram cargo. Initially, the orbiter would be able to stay in space for seven days at a time; later that period would be expanded to 30 days.

Those who had been responsible for the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in Houston were given new assignments related to Shuttle. Arnold Aldrich, Lunney's deputy during the mission, was placed in charge of program assessment in the Shuttle Program Office. Bob White and Frank Littleton went to work for him, evaluating the management aspects of that effort. Ed Smith turned his full attention to Shuttle simulation planning, which had received only part of his time during the ASTP years. Pete Frank, as Chief of the Flight Control Division, devoted his time to Shuttle flight control problems. R. H. Dietz divided his energies between Shuttle payload communications questions and feasibility studies of a large solar power [352] station satellite. Walt Guy also looked toward the future; his concern was new environmental control systems on the Shuttle orbiter.

Stafford, Slayton, and Brand, recently a crew, went their separate ways. In November 1975, Stafford left NASA to resume his career with the Air Force. With a second star on his shoulder, he assumed command of the Air Force Flight Test Center, Edwards Air Force Base, California. He was gone from JSC but not totally out of the picture. Shuttle would make its first approach and landing tests (ALT), after being carried aloft by a modified Boeing 747, on the dry lake bed at Edwards. Slayton, the director of ALT for NASA, would be visiting his alma mater - the test pilot school at Edwards, from which so many of the astronauts had graduated - to oversee those first unpowered glide flights. Brand, working in the Astronaut Office at JSC, had the responsibility for developing flight techniques for Shuttle, especially in entry and landing.

There was to be a hiatus in American manned space flight, but the pause should not be all that long. The approach and landing tests, begun in 1977, are to study the glide characteristics of the new orbiter. The first orbital flight test is set for 1979, and six developmental flights are on the drawing boards for mid-1980. Then Shuttle would begin regular and frequent operations, promising to become the DC-3 of outer space.

When Professor Bushuyev and his colleagues arrived in Houston for their final ASTP visit on 10 November 1975, many of the Shuttle changes were already visible at the space center. But the question on everyone's mind was, "What next with the Soviets?" Since the October 1973 meeting in Moscow, the Soviets had been deferring on the future systems aspect of the space cooperation agreement. Low, Lunney, and other Americans had continued to prod the Soviets about their plans for joint activities after ASTP, and each time the Soviets had asked the U.S. team to wait until after the joint flight. Bushuyev had told Lunney repeatedly that he did not have the personnel required to both prepare for ASTP and discuss future activities. So the talks that had begun as an effort to explore joint missions with future generations of spacecraft remained incomplete, despite recommendations from each Working Group concerning future operations based upon the lessons learned from ASTP.2

So how do we judge the success of the joint project? Evaluation of ASTP within the large context of continued cooperation between the United States and the Soviet Union will have to wait. Certainly, we can say that ASTP had a political dimension, one that reflected the improved relationship between the two countries that Presidents Nixon and Ford and Secretary of State Kissinger were seeking. But for now, the mission can be judged only upon its merits as a test flight. During the joint activity, the television media...

[353]

...presented a favorable, sometimes glowing, commentary on the live show from space, but several newspaper journalists were critical of what they termed "a costly space circus."3 Robert B. Hotz, editor-in-chief of Aviation Week and Space Technology, editorialized:

the real tragedy for this country was the decision to put its scarce space dollars into the political fanfare of Apollo-Soyuz. . . .

Now that it is over, it is apparent that the decision to fly Apollo-Soyuz, instead of another Skylab or whatever else could yield a good return on the Apollo investment already made, was as foolish and feckless as those other facets of the Nixon-Kissinger detente - the SALT talks, the trade deals and that great treaty that brought peace to Vietnam.4

This catchy, facile opinion was one widely held by many American journalists. As with so many aspects of American national policy, NASA's programs had always reflected the current environment of foreign affairs. Apollo, which had begun as a response from the Kennedy administration to the technological competition initiated by the Soviets in 1957, had been converted by NASA Administrators Paine and Fletcher into a means of cooperation with the Soviets. The joint flight could be seen as a part of detente, but the people at NASA saw it as much more.

On the most pragmatic level, ASTP gave the NASA team an opportunity to stay in the manned space flight business between the splashdown of Skylab 4 on 8 February 1974 and the first orbital flight test [354] of the Shuttle orbiter. Considerable thought by NASA planners had been given to flying the backup Skylab workshop, but this effort was abandoned in mid-l971 because it would have been too expensive; a duplicate Skylab would have drained scarce Shuttle funds. ASTP, on the other hand, gave the agency an opportunity to evaluate new hardware and flight techniques and the chance to carry a modest package of new or updated scientific experiments. Candidly, Chris Kraft thought that ASTP had been good for the American manned space program - good for morale, and it kept the flight team working. In addition, it was "a very big first step to international space flight cooperation."5

But could ASTP be equated with the seemingly endless Strategic Arms Limitations Talks (SALT)? Was it little more than the "great wheat deal in the sky?" Those who worked with the joint project did not think so. Unlike the arms talks, ASTP had a specific goal and a precise timetable. Once NASA and the Soviet Academy of Sciences agreed to fly in July 1975, the technological imperatives inherent in getting hardware ready for flight created an inner determinism within the project that helped to eliminate the possibility of either country stalling for political reasons. In the SALT negotiations, goals were less clearly defined and there was no deadline. While SALT participants continued to talk, the ASTP team brought their project to completion. The next steps in space cooperation, like the progress of the arms limitation discussions, would depend upon the international climate. Though ASTP had been a unique project, future cooperation, like SALT, was anchored in politics.

In April 1976, Tom Stafford noted that the Soviet and American space teams had met all their joint goals - they had designed, developed, and produced the hardware and systems whereby two spacecraft from different traditions could be joined together in space. "Where both systems were completely separate before," Stafford said, "we got together and worked [the differences] out. . . . the political implications were [such] that we could work in good faith." Stafford underscored good faith as "the key to something this technically difficult."6 Glynn Lunney agreed with this observation. The real breakthrough made in ASTP was in bringing together teams from the U.S. and U.S.S.R. to "implement, design, test and finally fly a project of this complexity." ASTP had been a big job. "Perhaps we've gotten a bit blase about it . . . but we [had] an awful lot of hardware that [had] to work well,"7 Lunney added.

Director Kraft pointed out that far from being a giveaway project, as many had claimed ASTP to have been, NASA had discovered many things about the Soviet space program that the American agency otherwise probably would not have learned. While he conceded that some of this [355] information could have been ferreted out if there had been a reason to do so, both sides had been too busy with their own projects to study in any depth the other's efforts. As the Americans and the Soviets worked together, they learned just how differently they had approached various aspects of manned space flight. Designer Caldwell Johnson, who had retired in 1974, commented on the prevailing Soviet policy of flying unmanned spacecraft to test out their systems. NASA had always built elaborate facilities on the ground to simulate the space environment. Each side preferred the approach to which it had become accustomed, and Johnson could not say in absolute terms which was the best.8

Stafford, Kraft, Lunney, and Johnson saw this adherence to tradition as the basic reason not to be concerned about the transfer of technological concepts or secrets to the Soviet Union. In terms of the pace at which aerospace technology developed, Apollo equipment was already old hat when the last flight thundered off the launch pad. There was really little to worry about when the Americans loaned an Apollo transceiver to the Soviets, since that piece of equipment was being replaced in Shuttle by newer transceivers. Even if the Soviets had taken the transceiver apart - and there was no evidence that they ever tried - without the manufacturing capacity to make the components, looking inside would have been akin to trying to assemble a solid black jigsaw puzzle.

Chris Kraft did see one area in which the Soviets might possibly have learned something from NASA that could benefit their space program. "I think they learned the large amount of complexity we go into to build our space vehicles . . . they learned generally how we go about manufacturing a space vehicle . . . [but] above all, [they] found out how we manage programs." Management was the key lesson that the Soviets could have learned from NASA. Still, Kraft was not certain that even after having been exposed to the process the Soviets understood how the Americans laid out their programs - how the agency projected what it was going to do in a milestone schedule; how the agency forced its personnel to manage resources as well as hardware; or how the agency integrated operational planning with the design and manufacture of equipment. "I doubt [if] they could take what we do and apply it to their way of doing business," he added. Stafford agreed: "the only thing they could have learned from us was management," but this lesson would have no significant impact on the Soviet space program, based upon the limited insights he had been able to gain about their managerial organization.9

While there was general belief within NASA that ASTP had been successful, there was uncertainty about what if anything would happen next with the Soviet Academy. During the winter of 1975-1976, the American [356] Government's attitude toward detente changed dramatically with the Soviet Cuban involvement in Angola. As detente disappeared from the foreign policy vocabulary, Chris Kraft reflected upon the meaning of these changes for international cooperation in space. "I guess that you would conjecture that this whole business of the tightening of the belt on both sides relative to each other's exploits in the world of foreign policy these days is certainly bound to rub off on these kinds of negotiations . . . unfortunate, but a fact of life."10 But Kraft was hopeful that ASTP was not the end of cooperation. He thought that the United States and NASA needed to "continue rubbing elbows with the Russians in a technical space flight sense. And I hope that we can develop a continuing rapport with those people . . . setting goals . . . between ourselves, that we both want to meet, and then working towards them, even if they are long range." Kraft went on:

Now that doesn't mean that we have got to fly in the same spacecraft . . . together, but if we have a cooperative attitude . . . and maybe plan some of our work together, I think [it] will lead to a quicker approach to the solution of problems; that would be very beneficial to the world, and certainly has got to be beneficial politically.11

George Low, who left NASA in the summer of 1976 to become president of Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, also maintained that Apollo-Soyuz had been a success. Looking back on the project, he believed that it had established a solid technical and managerial foundation upon which subsequent joint ventures could be built. Low also understood that cooperation was important for two reasons. First, space exploration was too costly for the Americans and Soviets to continue indefinitely their duplicative efforts. Second, he said, "We live in a rather dangerous world. Anything that we can do to make it a little less dangerous is worth doing. I think that ASTP was one of those things."12

In the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project, the Soviets and Americans had done the dramatic. Once they had proven that they could work together, they needed to develop other meaningful activities. There were indications that this could be done. Over a two-year period, 1974-1976, NASA scientists had worked with Soviet counterparts to develop a package of four biological experiments that were flown on the Soviet satellite Cosmos 782 (U.S.S.R./U.S. Biosatellite program).13 In mid-summer 1976, the three-volume Foundations of Space Biology and Medicine, first discussed during the 1964 Dryden-Blagonravov talks, was finally distributed in separate English and Russian editions as a joint publication of the Soviet Academy of Sciences and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration.14 In addition to the dramatic, the two sides were beginning to cooperate on more everyday activities. Still, the future was uncertain.

[357] Would the past be the prologue? Which past? The twelve years of competition or the five years of ASTP? In looking at the dozen years that preceded the joint flight, one would not likely have predicted such a cooperative venture. But single-minded individuals in the United States and the Soviet Union had pursued the goal of the docking mission and secured it. Looking toward the future, members of NASA's ASTP team could only hope that their efforts would lead to further cooperation and that the era of rivalry and competition would not return. But they knew from the moment that Apollo splashed down that the decision - to cooperate or to compete - was not theirs to make. They could only hope.

1. NASA, JSC, Announcement, "Establishment of Shuttle Payload Integration and Development Program Office," 4 Aug. 1975; and Edward C. Ezell, notes on telecon, 29 Oct. 1975.

2. "Minutes of Joint Meeting, USSR Academy of Sciences and US National Aeronautics and Space Administration," Nov. 1975.

3. Jonathan Spivak, "The First Space Handshake," Wall Street Journal, 22 July 1975; and news release, issued by the office of Senator William Proxmire, Wisconsin, 16 July 1975. Also see Rukopozhati v kosmose [Handshake in space] (Moscow, 1975), a collection of Soviet news accounts describing the joint mission, published by Izvestiya; and Kostantin D. Bushuyev, ed., Soyuz i Apollon, rasskazivayut sovetskie uchenie inzheneri i kosmonavti-ychastniki sovmestnikh rabot s amerikanskimi spetsialistami [Soyuz and Apollo, related by Soviet scientists, engineers, and cosmonauts - participants of the joint work with American specialists] (Moscow, 1976).

4. Robert Hotz, "Techno-Politics in Space," Aviation Week and Space Technology, 28 July 1975, p. 30.

5. Interview, Christopher C. Kraft-Ezell, 12 Apr. 1976.

6. Interview, Thomas P. Stafford-Ezell, 6 Apr. 1976.

7. ASTP mission commentary transcript, PC 36/E1, 17 July 1975.

8. Interview, Caldwell C. Johnson-Ezell, 27 Mar. 1975.

9. Interview, Kraft-Ezell, 12 Apr. 1976; and interview, Stafford-Ezell, 6 Apr. 1976.

10. Interview, Kraft-Ezell, 28 Mar. 1976.

11. Interview, Kraft-Ezell, 12 Apr. 1976.

12. Low to Monte D. Wright, NASA History Office, 2 Aug. 1976.

13. NASA News Release, HQ, 76-2, "Study of Cosmos Experiments Is Under Way," 13 Jan. 1976.

14. Melvin Calvin and

Oleg G. Gazenko, Foundations of Space

Biology and Medicine: Joint USA/USSR Publication in Three

Volumes (Washington and Moscow,

1975-1976).

Next