LARGE ISSUES OF POLICY

In 1961, when President Kennedy asked me to join his administration as head of NASA, I demurred and advised him to appoint a scientist or engineer. The President strongly disagreed. At a time when rockets were becoming so powerful that they could open up "the new ocean of space", he saw this Nation's most important needs as involving many large issues of national and international policy. He pointed to my experience in working with President Truman in the Bureau of the Budget and with Secretary Acheson in the State Department as well as to my experience in aviation and education as his reasons for asking me to take the job. Vice President Johnson also held this view, and emphasized the value of my experience with high-technology companies in the business world.I could not refuse this challenge, and I found that large issues of policy were indeed to occupy much of my energy. How could NASA, in the Executive Branch, do its work so as to facilitate responsible legislative actions in the Congress? How could public interest in space be made a constructive force? How could other nations' help be assured? In resolving policy and program questions, NASA was fortunate that Dr. Hugh Dryden, as Deputy Administrator, and Dr. Robert Seamans, as Associate Administrator, also had backgrounds of varied experience that could bring great wisdom to the decisions. We early formed a close relationship and stood together in all that was done.

Soon after my appointment, several significant events occurred in rapid succession. The first was a thorough review with Dr. Dryden and Dr. Seamans of what had been learned in both aeronautics and rocketry since NASA had been formed in 1958 to make projections of these advances into the future. We examined the adequacy of NASA's long-range plans and made estimates of the kind of scientific and engineering progress that would be required. We reviewed estimates of cost and found that sufficient priority and funds had not been provided.

|

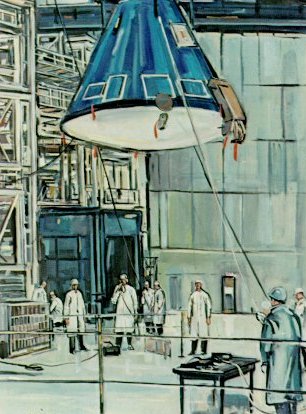

Tom O'Hara, CHECKING THE COMMAND MODULE, acrylic on paper |

The second event was the U.S.S.R.'s successful launch of the first man into Earth orbit, the Gagarin flight on April 12, 1961. A few weeks before this spectacular demonstration of the U.S.S.R.'s competence in rocketry, NASA had appealed to President Kennedy to reverse his earlier decision to postpone the manned spaceflight projects that were planned as a followup to the Mercury program. In his earlier decision, President Kennedy had approved funds for larger rocket engines but not for development of a new Generation of man-rated boosters and manned spacecraft. The "talking paper" that I used to urge President Kennedy to support manned flight included the following:

"The U.S. civilian space effort is based on a ten-year plan. When prepared in 1960, this ten-year plan was designed to go hand-in-hand with our military programs. The U.S. procrastination for a number of years had been based in part on a very real skepticism as to the necessity for the large expenditures required, and the validity of the goals sought through the space effort."

|

|

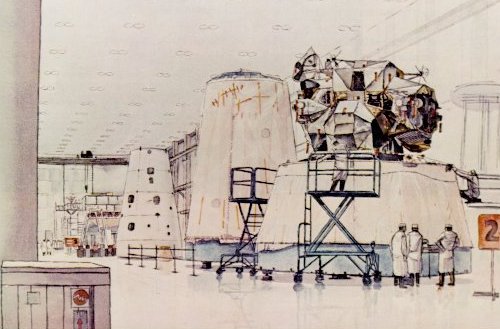

Billy Morrow Jackson, LUNAR MODULE WHITE ROOM, watercolor on paper |

"In the preparation of the 1962 budget, President Eisenhower reduced the $1.35 billion requested by the space agency to the extent of $240 million and specifically eliminated funds to proceed with manned spaceflight beyond Mercury. This decision emasculated the [NASA] ten-year plan before it was even one year old, and, unless reversed, guarantees that the Russians will, for the next five to ten years, beat us to every spectacular exploratory flight...."

"The first priority of this country's space effort should be to improve as rapidly as possible our capability for boosting large spacecraft into orbit, since this is our greatest deficiency...."

|

|

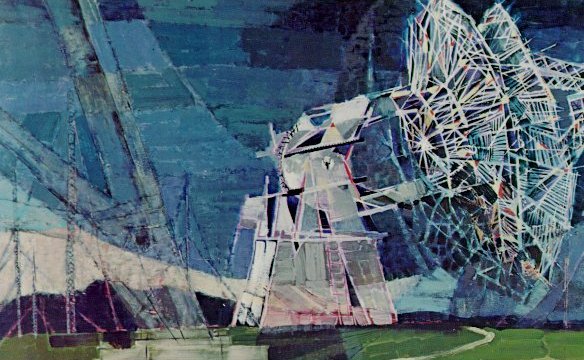

Paul Arlt, BIG DISH ANTENNAE, TANANARIVE, acrylic on canvas |

|

John Pike, BOILER PLATE, watercolor on paper |

"The funds we have requested for an expanded effort will bring the entire space agency program up to $1.42 billion in FY 1962 and substantially restore the ten-year program...."

"The United States space program has already become a positive force in bringing together scientists and engineers of many countries in a wide variety of cooperative endeavors. Ten nations all have in one way or another taken action or expressed their will to become a part of this imaginative effort. We feel there is no better means to reinforce our old alliances and build new ones...."

|

| Robert McCall, APOLLO 8 COMING HOME, oil on panel |

"Looking to the future, it is possible through new technology to bring about whole new areas of international cooperation in meteorological and communication satellite systems. The new systems will be superior to present systems by a large margin and so clearly in the interest of the entire world that there is a possibility all will want to cooperate - even the U.S.S.R."

|

Paul Calle, INSIDE GEMINI SPACECRAFT, pencil on paper |

President Kennedy's March decision had been to proceed cautiously. He had added $126 million to NASA's budget, mostly for engines, but postponed the start on manned spacecraft. In March of 1961, he was not yet ready to move unambiguously toward a resolution of the great national and international policy issues about which he spoke when he asked me to join the administration.

| Next |