A LUNAR RICKSHAW

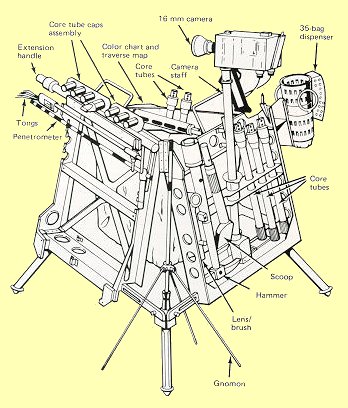

Ed and I worked on the surface for 4 hours and 50 minutes during our first EVA; after the return to Antares, a long rest period, and then resulting, we began the second EVA. This time we had the MET- modularized equipment transporter, although we called it the lunar rickshaw- to carry tools, cameras, and samples so we could work more effectively and bring back a larger quantity of samples.

|

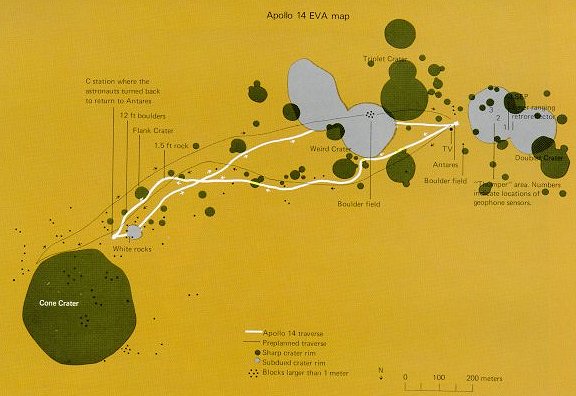

| The planned traverse route for the second EVA is shown by a fine black line an this map of the Apollo 14 site. The heavier white line is the traverse actually covered. The craters and boulders encountered are plotted, as are the locations of the emplaced experiments. Such maps are essential for an understanding of the sample sources and the experiment data. |

Our planned traverse was to take us from Antares more or less due east to the rim of Cone crater. That traverse had been chosen because scientists wanted samples and rocks from the crater's rim. The theory is that the oldest rocks from deep under the Moon's surface were thrown up and out of the crater by the impact, and that the ones from the extreme depth of the crater were to be found on the rim.

On our way to the crater, one of the first things Ed did was to take a magnetometer reading at the first designated site. When he read the numbers over the air, there was some excitement back at Houston because the readings were about triple the values gotten on Apollo 12. They were also higher than the values Stu was reading in the Kitty Hawk, and so it seemed that the Moon's magnetic field varied spatially.

| The well-stocked tool rack at left, which fitted neatly on the rickshaw, was at least better than traipsing about carrying everything, including samples already collected. But it proved to be a drag in deep dust, easier to carry than to tow. The problem of doing on-the-spot lunar geologising in an efficient way awaited the electric Rover. |

Our first sampling began a little further on, in a rock field with boulders about two or three feet along the major dimension. These were located in the centers of a group of three craters, each about sixty feet across. Like the bulk of the samples brought back, these were documented samples. That means photographing the soil or rocks, describing them and their position over the voice link to Mission Control, and then putting the sample in a numbered bag, identifying the bag at the same time on the voice hookup.

Apollo 14 tried an experiment to do something constructive about the dust that plagued all of the missions. NASA engineers wanted to check out some of the finishes proposed for the Rover and other pieces of operating equipment. I had a group of samples - material chips with different finishes - and I dusted them with the surface dust, shook them off, and then brushed one set to try to determine the abrasive effects, if any, of such dust removal. The other set was left unbrushed as a control sample. All this was of course recorded with the closeup camera.

The mapped traverse was to take us nearly directly to the rim of Cone crater, a feature about 1000 feet in diameter. As we approached. the boulders got larger, up to four and five feet in size. And at this time, the going started to get rough for us. The terrain became more steep as we approached the rim, and the increased grade accentuated the difficulty of walking in soft dust.

| Next |