Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

TIRED, HUNGRY, WET, COLD, DEHYDRATED

The trip was marked by discomfort beyond the lack of food

and water. Sleep was almost impossible because of the cold. When

we turned off the electrical systems, we lost our source of heat,

and the Sun streaming in the windows didn't much help. We were as

cold as frogs in a frozen pool, especially Jack Swigert, who got

his feet wet and didn't have lunar overshoes. It wasn't simply

that the temperature dropped to 38 F: the sight of perspiring

walls and wet windows made it seem even colder. We considered

putting on our spacesuits, but they would have been bulky and too

sweaty. Our teflon-coated inflight coveralls were cold to the

touch, and how we longed for some good old thermal underwear.

| | |

A beautiful sight! Two flight controllers at the

Mission Control Center watch the parachute deployment as Odyssey

floats down toward a gentle landing in the Pacific near

American Samoa. Splashdown, at 1:07 p.m. EST, brought

down the curtain on the most harried and critical

emergency of the entire manned space program.

|

| | |

The charred command module splashed down less

than four miles from the recovery ship USS Iwo Jima. Three

very tired, hungry, cold, dehydrated astronauts

await a ride up into the recovery helicopter.

They were aboard the recovery ship less than

one hour after touching down in the Pacific.

|

The ground, anxious not to disturb our homeward trajectory,

told us not to dump any waste material overboard. What to do with

urine taxed our ingenuity. There were three bags in the command

module; we found six little ones in the LM, then we connected a

PLSS condensate tank to a long hoses and finally we used two

large bags designed to drain remaining water out of the PLSS's

after the first lunar EVA. I'm glad we got home when we did,

because we were just about out of ideas for stowage.

A most remarkable achievement of Mission Control was quickly

developing procedures for powering up the CM after its long cold

sleep. They wrote the documents for this innovation in three

days, instead of the usual three months. We found the CM a cold,

clammy tin can when we started to power up. The walls, ceiling,

floor, wire harnesses, and panels were all covered with droplets

of water. We suspected conditions were the same behind the

panels. The chances of short circuits caused us apprehension, to

say the least. But thanks to the safeguards built into the

command module after the disastrous fire in January 1967, no

arcing took place. The droplets furnished one sensation as we

decelerated in the atmosphere: it rained inside the CM.

Four hours before landing, we shed the service module;

Mission Control had insisted on retaining it until then because

everyone feared what the cold of space might do to the

unsheltered CM heat shield. I'm glad we weren't able to see the

SM earlier. With one whole panel missing, and wreckage hanging

out, it was a sorry mess as it drifted away.

|

Haise, Lovell, and Swigert step off the recovery helicopter

to the Iwo Jima in the South Seas. The crew lost a total

of 31.5 pounds; Lovell alone 14 pounds - records in both cases.

Dehydroted and exhausted, Haise was invalided

three weeks by infection.

|

|

In Honolulu Lovell is joyously united with wife

Marilyn after she and Mary Haise and bachelor

Swigert's parents had flown from Houston

with President Nixon. During the Apollo 8 mission

sixteen months earlier, Lovell had

nicknamed a crater on Moon "Mount Marilyn".

|

|

Fred and Mary Haise draped with Hawaiian leis.

A physician had accompanied pregnant Mary Haise to Honolulu

in the event Air Force One should have its first

airborne birth. However, the Haise's fourth

child Thomas did not arrive until ten weeks later.

|

|

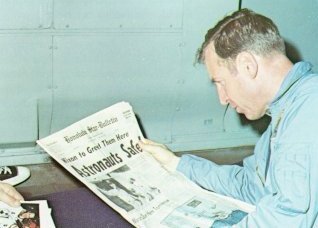

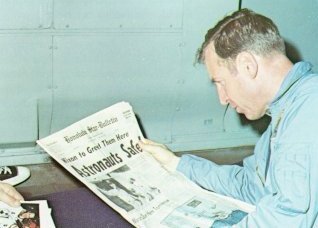

"We didn't realize the complete magnitude of this flight",

said Lovell, "until we got back home and started reading

about it." Christian Science Monitor said: "Never in recorded

history has a journey of such peril been watched and

waited-out by almost the entire human race."

|

Three hours later we parted with faithful Aquarius, rather

rudely, because we blasted it loose with pressure in the tunnel

in order to make sure it completely cleared. Then we splashed

down gently in the Pacific Ocean near Samoa, a beautiful landing

in a blue-ink ocean on a lovely, lovely planet.

Nobody believes me, but during this six-day odyssey we had

no idea what an impression Apollo 13 made on the people of Earth.

We never dreamed a billion people were following us on television

and radio, and reading about us in banner headlines of every

newspaper published. We still missed the point on board the

carrier Iwo Jima, which picked us up, because the sailors had

been as remote from the media as we were. Only when we reached

Honolulu did we comprehend our impact: there we found President

Nixon and Dr. Paine to meet us, along with my wife Marilyn,

Fred's wife Mary (who being pregnant, also had a doctor along

just in case), and bachelor Jack's parents, in lieu of his usual

airline stewardesses.

| | |

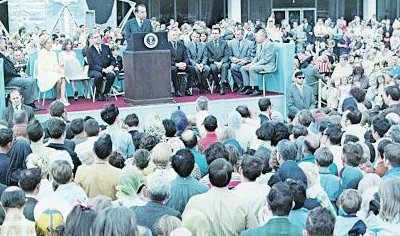

In Houston the 37th President pays tribute to the men

who performed miracles in Mission Control to save Apollo

13. To President's right are NASA Administrator

Thomas Paine and Mrs. Nixon. To his left: Flight directors

Eugene Kranz, Gerald Griffin, Milton Windler (the fourth,

Glynn Lunney, is behind lectern), then Chief Astronaut

Donald K. Slayton, James A. Lovell III (in uniform),

and Sigurd Sjoberg, Director of Flight Operations, who in

behalf of "the ground" received the Nation's highest award,

Medal of Freedom.

|

In case you are wondering about the cause of it all, I refer

you to the report of the Apollo 13 Review Board, issued after an

intensive investigation. In 1965 the CM had undergone many

improvements, which included raising the permissible voltage to

the heaters in the oxygen tanks from 28 to 65 volts DC.

Unfortunately, the thermostatic switches on these heaters weren't

modified to suit the change. During one final test on the launch

pad, the heaters were on for a long period of time. "This

subjected the wiring in the vicinity of the heaters to very high

temperatures (1000 F), which have been subsequently shown to

severely degrade teflon insulation . . . the thermostatic

switches started to open while powered by 65 volts DC and were

probably welded shut." Furthermore, other warning signs during

testing went unheeded and the tank, damaged from 8 hours

overheating, was a potential bomb the next time it was filled

with oxygen. That bomb exploded on April 13, 1970 - 200,000 miles

from Earth.

|

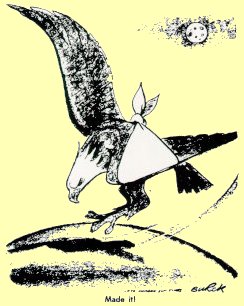

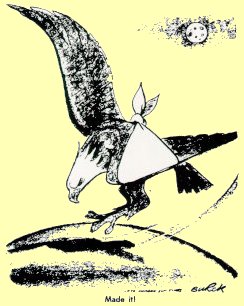

A collective sigh of relief rose from the millions

following the drama of Apollo 13 when the Odyssey splashed

down. The CM-shaped bandage on this eagle cleverly depicts

the flight home. "Only in a formal sense will Apollo

13 go into history as a failure", editorialized

The New York Times.

|

|