Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

THE MISSIONS OF UNDERSTANDING

The last three Apollo journeys were great missions of

understanding during which our interpretation of the evolution of

the Moon evolved. In July 1971 the first of these missions,

Apollo 15, visited Hadley Rille at the foot of the Apennine

Mountains. Apollo 15 gave lunar exploration a new scale in

duration and complexity. Col. David R. Scott, Col. James B.

Irwin, and Lt. Col. Alfred M. Worden looked at the whole planet

for 13 days through the eyes of precision cameras and electronics

as well as the eyes of men. Scott and Irwin spent nearly 67 hours

on the Moon's surface, and were the first to use a wheeled

surface vehicle, the Rover, to inspect a wide variety of

geological features. Finally, before returning to Earth, they

placed a small satellite in lunar orbit that greatly expanded our

knowledge of the distribution and geological correlation of

gravitational and magnetic variations within the Moon's crust.

| | |

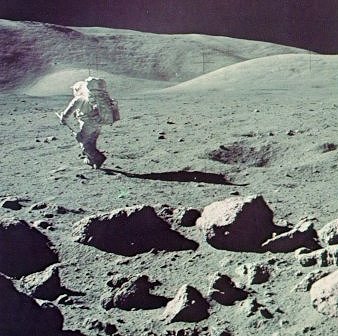

Sampling scoop in hand, I go questing at Station 5 by Camelot

Crater. At this point I had already collected a load of samples,

and will shortly curve back to the Rover, off-camera at left, to

unload. This was our second EVA, covering some 11 miles.

|

The varied samples and observations from the vicinity of

Hadley Rille and the mountain ring of Imbrium called the Apennine's

pushed knowledge of lunar processes back past the four-billion-

year barrier we had seemed to see on previous missions. We also

discovered that lunar history behind this barrier was partially

masked by multiple cycles of impact melting and fragmentation.

Nevertheless, the rock fragments we sampled gave vague glimpses

into the first half-billion years of lunar evolution and into

some details of the nature of the melted shell. Part of this view

into the past was provided by the well-known "Genesis Rock" of

anorthosite (a plagioclase-rich rock). In addition, we expanded

our understanding of the complex volcanic processes that created

the present surfaces of the maria. These processes were now seen

to have included not only the internal separation of minerals

within lava flows but possible processes of volcanic erosion and

fracturing that could have created the rilles.

| | |

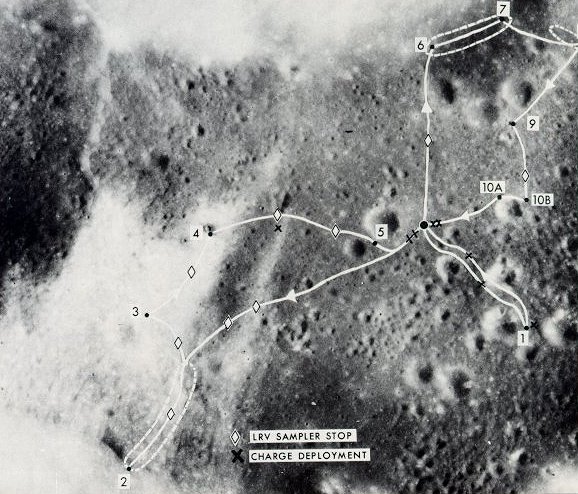

Our three traverses on Apollo 17 came very close to

those we had preplanned, differing only because of

unexpected findings. The fist run was a mile and a quarter to

Steno Crater and back, in the 4 o'clock position above. The second

was the longest, at 5 o'clock. At station 4 near Shorty Crater

we found the orange soil (see here).

The third run, at 12 to 1 o'clock, was more than six miles. The

great fractured boulder shown here

is on the slope near Station 6.

|

The Apollo 15 astronauts placed instruments on the Moon

which, in conjunction with earlier missions, finally established

a geophysical net of stations. Of particular importance was a net

of seismometers by which we began to decipher the inner structure

of the Moon. Correlations of information from these stations with

other facts enabled us to interpret several major portions of the

interior. The Moon's crustal rocks, rich in the calcium and

aluminum silicate plagioclase, are broken extensively near the

surface but more coherent at depths from 15 to 40 miles. The

crust rests on an upper mantle 125 to 200 miles thick that

contains the magnesium and iron silicates, pyroxene and olivine.

From about 200 or 250 to about 400 miles deep, the lower mantle

is possibly similar to some types of stony meteorites called

chondrites. From about 400 miles to about 700 miles deep, the

chondrite material appears to be locally melted and seismically

active. There are also many reasons now to believe that the Moon

has an iron-rich core from about 700 miles deep to its center at

1080 miles that produced a global magnetic field until only

recent times.

| | |

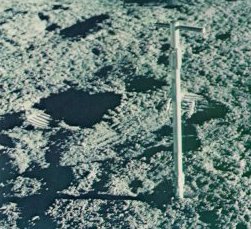

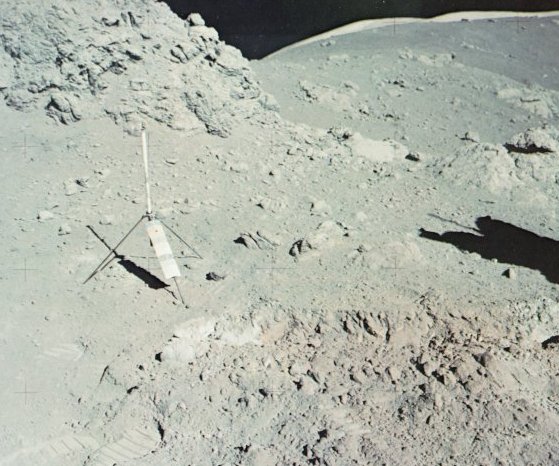

Sampling by scoop was the main way we obtained the large numbers

of small samples that provide good statistical information about

the composition of the surface. That instrument to the left of

Apollo 15's Jim Irwin is a gnomon. It provides a vertical-seeking

rod of known length, a color chart, and a shadow - all useful

for calibrating pictures.

|

| | |

Sampling tongs and coring tubes gave us other means of

collecting special samples. The spring-loaded tongs below let us

pick up small rocks and fragments without getting down on our

knees or otherwise reaching way down with clumsy gloves. The

core tubes were hammered down into the soil and then drawn back

out and capped. They gave us a way to collect sections of soil that

preserved the relative relationships undisturbed.

|

The geophysical station at Hadley-Apennines also told us

that the flow of heat from the Moon was possibly two times that

expected for a body having approximately the same radioisotopic

composition as the Earth's mantle. If true, this tended to

confirm earlier suggestions that much of the radioisotopic

material in the Moon was concentrated in its crust. Otherwise,

the interior of the Moon would be more fluid and show greater

activity than we sense with the seismometers.

| | |

Finding orange soil near Station 4 on Apollo 17 at the

time when oxygen was running low kept us on the jump. We dug a trench

8 inches deep and 35 inches long, took samples of the orange soil and

nearby gray soil, drove a core tube into the deposit, sampled

surrounding rocks, described and photographed the crater site in

detail, and packed the samples - all in 35 minutes. The effort gave

scientists a most unusual sample: very small beads of orange volcanic

glass, formed in a great eruption of fire fountains over

3.5 billion years ago.

|

|

Rocks too big to bring back were studied where

they were, described and photographed, and

sampled by chipping pieces from their corners.

If we could roll the rock over, as above,

we could take soil samples underneath that had been

shielded from the effects of solar and cosmic radiation.

|

We began with Apollo 15 to be able to correlate our landing

areas around the whole Moon by virtue of very-high-quality

photographs and geochemical x-ray and gamma-ray mapping from

orbit. The x-ray remote sensing investigations disclosed the

provincial nature of lunar chemistry, particularly by

highlighting differences in aluminum-to-silicon and magnesium-to-

silicon ratios within the maria and the highlands. By outlining

variations in the distribution of uranium, thorium, and

potassium, the gamma-ray information suggested that large basin-

forming events were capable of creating geochemical provinces by

the ejection of material from depths of six or more miles.

Possibly of equal importance with all these findings by

Apollo 15 was the discovery - shared through television by

millions of people - that there existed beauty and majesty in

views of nature that had previously been outside human

experience.

The mission of Apollo 16 to Descartes in April 1972 revealed

that we were not yet ready to understand the earliest chapters of

lunar history exposed in the southern highlands. In the samples

that Capt. John W. Young, Comdr. Thomas K. Mattingly. and Col.

Charles M. Duke, Jr., obtained in the Descartes area, the major

central events of that history seemed to be compressed in time

far more than we had guessed. There are indications that the

formation of the youngest major lunar basins, the eruption of

light-colored plains materials, and the earliest extrusions of

mare basalts required only about 100 million years of time around

3.9 billion years ago.

|

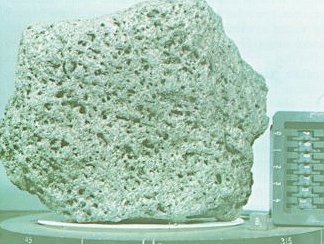

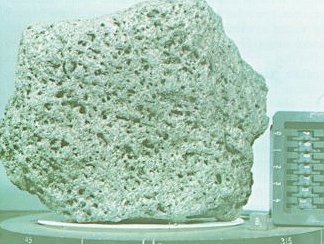

The basaltic lavas of the lunar maria, like this

sample photographed after return to a laboratory

on Earth, tell much about the partial melting of the

Moon between three and four billion years ago.

This sample, 70017, is identified in its

documentation photograph by the number of the

counter and by the B orientation code.

|

|

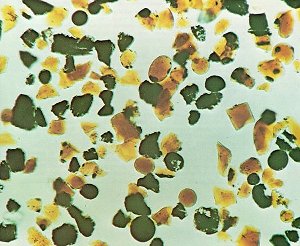

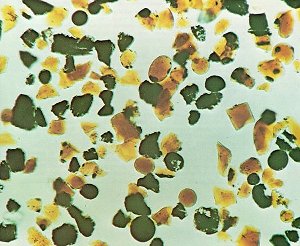

Ancient beads of orange volcanic glass in

the photomicrograph above have revealed secrets

of the Moon's deep interior. Produced most likely

by the partial melting of the lunar mantle,

and discovered by Apollo 17, these beads are

unusualy rich in such volatile elements as lead,

zinc, tellurium, and sulfur. This indicates not

only volcanic origin but also derivation from

rocks possibly as deep as 200 miles in the

Moon. Similar glass beads, green in color,

were discovered by Apollo 15.

|

The extreme complexity of the problem of interpreting the

lunar highland rocks and processes became evident even as the

Apollo 16 mission progressed. Rather than discovering materials

of clearly volcanic origin as many expected, the men found

samples that suggested an interlocking, sequence of igneous and

impact processes. A new chemical rock group known as "very high

aluminum basalts" could be defined, although its ancestry

relative to other lunar materials was obscured by later events

that gave the cratered highlands their present form. The results

of Apollo 16 have within them an integrated look at almost all

previously and subsequently identified highland rock types. With

this complexity comes a unique, as yet unexploited, opportunity

to understand the formation and modification of the Moon's early

crust and potentially that of the Earth.

The materials found in the Descartes region were similar to

those sampled slightly earlier by Luna 20 in the Apollonius

region. But there were significant differences in the aluminum

content of debris representative of the two regions. Also there

were differences in the abundance of fragments of distinctive

crystalline rocks known as the anorthosite-norite-troctolite

suite. After Apollo 15, this suite of rocks had been recognized

as possibly being a much reworked leftover of at least portions

of the ancient lunar crust. Luna 20 and Apollo 16 confirmed its

great importance to the understanding of the ancient melted

shell.

|