Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

A MAJOR THERMAL EVENT?

The last crystallization age of some of the Apollo 16 rocks

appeared to be about 3.9 billion years, and continued to indicate

that this age is a major turning point in lunar history. This

general age for the cooling of highland-like materials also was

found to hold for the ejecta blanket of the Imbrium Basin at Fra

Mauro, for the rocks of the Apennines, and later for some of the

highland rocks at Taurus-Littrow. This limit suggested (1) a

major thermal event associated with the formation of several

large basins over a relatively short time, or (2) a major thermal

event associated with the formation of the light-colored plains,

or (3) the rapid cessation of the period of major cratering that

continually reworked the highlands until most vestiges of

original ages had disappeared and only the last local impact

event was recorded. As we attempt to explain the absence of very

old rocks on Earth, we should not forget these possibilities for

resetting our own geologic clocks.

|

The eyes of geochemical sensors peer through an opening

in the sides of Apollo 15 CSM Endeavour. The instruments

gave us broad-scale remote sensing of the lunar surface,

allowing data from sampies collected on the surface to

be correlated across major areas of the Moon. Included

were precision cameras and spectrometers that sensed x-rays,

gamma rays, infrared radiation, and the chemical ions in the

ultrathin lunar atmosphere. Apollo 15 cameras supplied

much imagery used to plan our Apollo 17 exploration.

|

| | |

Adrift between the Earth and the Moon, Ron Evans retrieved

the film canister of the mapping cameras on the day after

Apollo 17 left lunar orbit. His space walk lasted an hour,

and resulted in the successful retrieval of data from three

experiments. Ron's oxygen was fed from the spacecraft through

the umbilical hose, with an emergency supply on his back.

I was in the open hatch to help in retrieval, which was

necessary because the service module would be jettisoned

before we reentered the Earth's atmosphere.

|

Apollo 16 continued the broad-scale geological, geochemical,

and geophysical mapping of the Moon's crust from orbit begun by

Apollo 15. This mapping greatly expanded our knowledge of

geochemical provinces and geophysical variations, and has helped

to lead to many of the generalizations it is now possible to make

about the evolution of the lunar crust.

Apollo 17 carried Capt. Eugene A. Cernan, Capt. Ronald

Evans, and me in December 1972 to the valley of Taurus-Littrow

near the coast of the great frozen basaltic "sea" of Serenitatis.

The unique visual character and beauty of this valley was, I

hope, seen by most people on television as we saw it in person.

The unique scientific character of this valley has helped to

lessen our sadness that Apollo explorations ended with our visit.

It would have been hard to find a better locality in which to

synthesize and expand our ideas about the evolution of the Moon.

| |

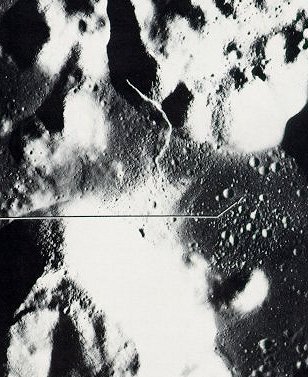

Apollo 17 photographed itself in the frame at right from its panoramic

camera, which shows the valley of Taurus-Littrow after the landing of

Challenger. The landing point (see inset at left) is revealed by

a bright spot, produced by the effects of the descent-engine exhaust.

A reflection from and shadow of the LM are also visible in

high-quality prints. The panoramic camera has an absolute resolution of

about 1 meter in best prints.

Detailed analysis of this panoramic photograph indicates that

the light-colored avalanche, and many of the craters on the valley

floor, are probably the result of the impact of material ejected

some 50 million years ago from the crater Tycho 1300 miles to the

southwest. Such orbital data have been invaluable in expanding the

context of our interpretations of samples and data that were returned

from explorations on the surface.

|

At Taurus-Littrow we looked at and sampled the ancient lunar

record ranging back from the extrusion of the oldest known mare

basalts, through the formation of the fragmental rocks of the

Serenitatis mountain ring, and thence back into fragments in

these rocks that may reflect the very origins of the lunar crust.

We also found and are now studying volcanic materials and

debris-forming processes that range forward from the formation of

the earliest mare basalt surface through 3.8 billion years of

modification of that surface.

The pre-mare events in the Taurus-Littrow region that

culminated in the formation of the Serenitatis Basin produced at

least three major and distinctive units of complex fragmental

rocks. The oldest of these rock units contains distinctive

fragments of crystalline magnesium and iron-rich rocks that

appear to be the remains of the crystallization of the melted

shell. This conclusion is supported by a crushed rock of

magnesium olivine with an apparent crystallization age of 4.6

billion years. The old fragmental rock unit containing these

ancient fragments was intruded and locally altered by another

unit which was partially molten at the time of intrusion about

3.9 billion years ago. Such intrusive fragmental rocks are

probably the direct result of the massive impact event that

formed the nearby Serenitatis Basin; however, an internal

volcanic origin cannot yet be ruled out. The third fragmental

rock unit seems to cap the tops of the mountains and it may be

the ejecta from one of the several large old basins within range

of the valley. This unit contains a wide variety of fragments of

the lunar crust, including barium-rich granitic rock.

| | |

A landing site not visited, the crater Alphonsus is shown

in this Apollo 15 mapping-camera picture. A point near the

right edge of the crater floor in this southward-looking

view was once the leading candidate for our landing site

in Apollo 17. However, the need for greater geologic and

geographic variety resulted in final selection of Taurus-Littrow

instead. Our regret is that both could not have been explored.

|

The valley of Taurus-Littrow and other low areas nearby

appear to be a fortuitous window that exposes some of the oldest,

if not the oldest, mare basalt extrusives on the Moon. They are

about 3.8 billion years old, and are 50 to 100 million years

older than the basalts at Tranquility Base. They also contain

titanium oxide in amounts up to 13 percent by weight.

|