TESTING THE SURFACE

Surveyor, which had been formally approved in the spring of 1960, was originally conceived for the scientific investigation of the Moon's surface. As in the case of the Ranger, its use was redirected according to the needs of Apollo.With the proposed addition of an orbiting version of Surveyor, later to become Lunar Orbiter, the unmanned lunar-exploration program in support of Apollo shaped up this way: Ranger would provide us with our first look at the surface, Surveyor would make spot checks of the mechanical properties of the surface; and Lunar Orbiter would supply data for mapping and landing-site selection. The approach was sound enough, but carrying it out led us into a jungle of development difficulties.

Few space projects short of Apollo itself embodied the technological audacity of Surveyor. Its Atlas-based launch vehicle was to make use of an entirely new upper stage, the Centaur, the world's first hydrogen-fueled rocket. It had been begun by the Department of Defense and later transferred to NASA. Surveyor itself was planned to land gently on the lunar surface, set down softly by throttable retrorockets under control of its own radar system. It was to carry 350 pounds of complex scientific instruments. Responsibility for continuing the Centaur development was placed with the Marshall Space Flight Center, with General Dynamics the prime contractor. JPL took on the task of developing the Surveyor, and the Hughes Aircraft Company won the competition for building it. We soon found that it was a very rough road. Surveyor encountered a host of technical problems that caused severe schedule slips, cost growth, and weight growth. The Centaur fared little better. Its first test flight in 1962 was a failure. Its lunar payload dropped from the planned 2500 pounds to an estimated 1800 pounds or less - not sufficient for Surveyor. Its complex multistart capability was in trouble. Wernher von Braun, necessarily preoccupied with the development of Saturn, recommended cancelling Centaur and using a Saturn-Agena combination for Surveyor.

At this point we regrouped. Major organizational changes were made at JPL and Hughes to improve the development and testing phases of Surveyor. NASA management of Centaur was transferred to the Lewis Research Center under the leadership of Abe Silverstein, where it would no loncer have to compete with Saturn for the attention it needed to succeed. Its initial capabilities were targeted to the minimum required for a Surveyor mission - 2150 pounds on a lunar-intercept trajectory. This reduced weight complicated work on an already overweight Surveyor, and the scientific payload dropped to about 100 pounds.

It all came to trial on May 31, 1966, when Surveyor I was launched atop an Atlas-Centaur for the first U.S. attempt at a soft landing. On June 2, Surveyor I touched down with gentle perfection on a level plain in the Ocean of Storms, Oceanus Procellarum. A large covey of VIPs had gathered at the JPL control center to witness the event. One of them, Congressman Joseph E. Karth, whose Space Science and Applications Subcommittee watched over both Surveyor and Centaur, had been both a strong supporter and, at times, a tough critic of the program. The odds for success on this complex and audacious first mission were not high. I can still see his broad grin at the moment of touchdown, a grin which practically lighted up his corner of the darkened room. We sat up most of the night watching the first of the 11,240 pictures that Surveyor I was to transmit.

Four months prior to Surveyor's landing, on February 3, 1966, the Russian Luna 9 landed about 60 miles northeast of the crater Calaverius, and radioed back to Earth the first lunar-surface pictures. This was an eventful year in lunar exploration, for only two months after Surveyor I, the U.S. Lunar Orbiter I usbered in that successful and richly productive series of missions.

|

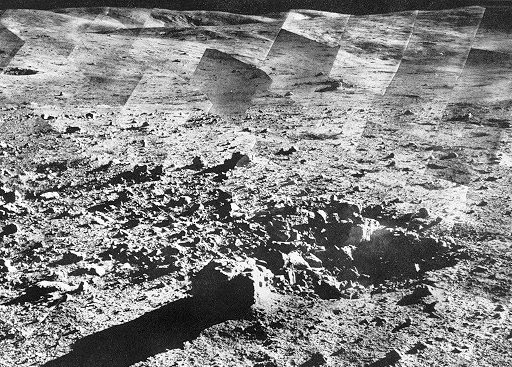

| The rolling highlands north of Tycho are portrayed with remarkable clarity in this mosaic assembled from among Surveyor VII's 21,038 photographs. To estimate scale, the boulder in the foreground is 2 feet across, the crater about 5 feet wide, and the far hills and ravines some 8 miles distant. |

|

| Surveyor VII's "garden" was a heavily worked-over area next to the spacecraft. Trenches were dug with the articulated scoop to give data on the mechanical properties of the surface. At left is the alpha-backscattering instrument that provided accurate measurements of the chemical composition of the surface. |

Surveyor found, as had Luna before it, a barren plain pitted with countless craters and strewn with rocks of all sizes and shapes. No deep layer of soft dust was found, and analysts estimatcd that the surface appeared to be firm enough for both spacecraft and men. The Surveyor camera, which was more advanced than Luna's, showed very fine detail. The first frame transmitted to Earth showed a footpad and its impression on the lunar surface, which we had preprogrammed just in case that was the only picture that could be received. At our first close glimpse of the disturbed lunar surface, the material seemed to behave like moist soil or wet sand, which, of course, it was not. Its appearance was due to the cohesive nature of small particles in a vacuum.

Surveyor II tumbled during a midcourse maneuver and was lost, but on April 19, 1967, Surveyor III made a bumpy landing inside a 650-foot crater in the eastern part of the Sea of Clouds. Its landing rockets had failed to cut off and it skittered down the inner slope of a crater before coming to rest. Unlike its predecessors, Surveyor III carried a remotely controlled device that could dig the surface. During the course of digging, experimenters dropped a shovelful of lunar material on a footpad to examine it more closely. When Surveyor III was visited by the Apollo 12 astronauts 30 months later in 1970, the little pile was totally undisturbed, as can be seen in the photograph reproduced at the beginning of Chapter 12.

The historic rendezvous of Apollo 12 with Surveyor III would never have been possible without the patient detective work of Ewen Whitaker of the University of Arizona. The difficulty was that the landing site of Surveyor was not precisely known. Using Surveyor pictures of the inside of the crater in which it had landed, Whitaker compared surface details with details visible in Orbiter photographs of the general area that had been taken before the Surveyor landing. He eventually found a 650-foot crater that matched, and concluded that that was where Surveyor must be. Thus the uncertainty in Surveyor's location was reduced from several miles down to a single crater. By using Orbiter photographs as a guide, Apollo 12 was able to fly down a "cratered trail" to a landing only 600 feet away from Surveyor.

Surveyor IV failed just minutes before touchdown, but the last three Surveyors were successful. On September 10, 1967, Surveyor V landed on the steep inner slopes of a 30 by 40 foot crater on Mare Tranquillitatis. It carried a new instrument, an alpha-backscattering device developed by Anthony Turkevich of the University of Chicago. With this device he was able to make a fairly precise analysis of the chemical composition of the lunar-surface material, which he correctly identified as resembling terrestrial basalts. This conclusion was also supported by the manner in which lunar material adhered to several carefully calibrated magnets on Surveyor. Two days after landing, Surveyor V's engines were reignited briefly to see what effect they would have on the lunar surface. The small amounts of erosion indicated that this would pose no real problem for Apollo, though perhaps causing some loss of visibility just before touchdown.

Surveyor VI checked out still another possible Apollo site in Sinus Medii. The rocket-effects experiment was repeated and this time the Surveyor was "flown" to a new location approximately 8 feet from the original landing point. Some of the soil thrown out by the rockets stuck to the photographic target on the antenna boom, as shown here.

The last Surveyor was landed in a hiiyhland area just north of the crater Tycho on January 9, 1968. A panoramic picture of this ejecta field taken by Surveyor VII is shown here as well as a mosaic of its surface "gardening" area. I remember walking into the control room at JPL at the moment the experimenters were attempting to free the backscatter instrument, which had hung up during deployment. Commands were sent to the surface sampler to press down on it. The delicate operation was being monitored and guided with Surveyor's television camera. When I started asking questions, Dr. Ron Scott of Cal Tech crisply reminded me that at the moment they were "quite busy". I held my questions - and they got the stuck instrument down to the surface. It seemed almost unreal to be remotely repairing a spacecraft on the Moon some quarter of a million miles away.

Before the launch of Surveyor I, in the period when we faced cost overruns and deep technical concerns, NASA and JPL had pressed the Hughes Aircraft Company to accept a contract modification that would give up some profit already earned in favor of increased fee opportunities in the event of mission successes. They accepted, and this courageous decision paid off for both parties. NASA of course was delighted with five out of seven Surveyor successes.

LUNAR OBITER PHOTOGRAPHY

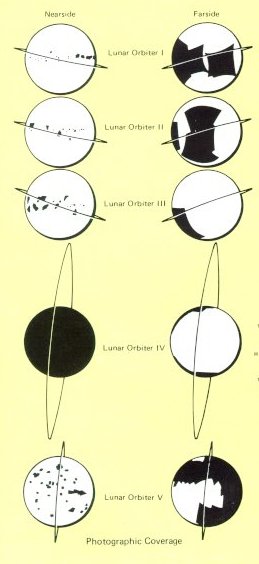

| Lunar Orbiter was planned for use in conjunction with Surveyor; one spacecraft class was to sample the surface of the Moon, and the other was to map potential Apollo landing sites. Five Orbiters were flown, so successfully that they returned not only precision stereo-photography of all contemplated landing areas but also photographed virtually the entire Moon, including the far side. Included in the photographs returned were the landed Surveyor I, the impact crater caused by Ranger VIII, and many breathtaking images of high scientific value. Orbiter coverage is shown at the left. |

|

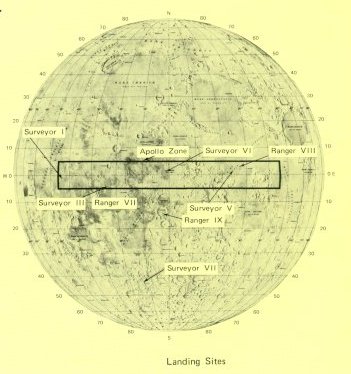

| The equatorial Apollo landing zone with its precursor Ranger and Surveyor landing sites. |

|

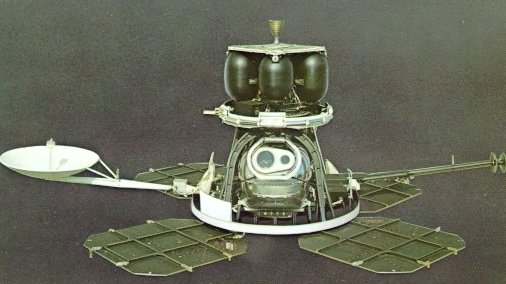

| The two-eyed robot above is the spacecraft that mapped the Moon for Apollo planners. It was built by Boeing for the NASA Langley Research Center, and launched by an Atlas-Agena. Weighing 850 pounds, it drew electrical power from the four solar-cell arrays shown, which delivered a maximum of 450 watts. The rocket motor at top provided velocity changes for course corrections. Guidance was provided by inertial reference (three-axis gyros), celestial reference (Sun and Canopus sensors), and cold-gas jets to give attitude control. Because it would necessarily be out of touch with Earth during part of every orbit, it carried a computer-programmer that could accept and later carry out up to 16 hours of automatic sequenced operation. |

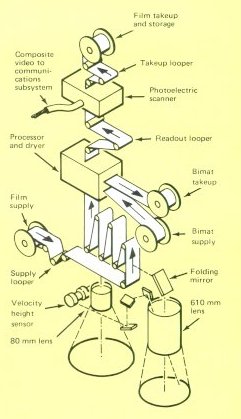

| It was in its photo system that Orbiter was most unconventional. Other spacecraft took TV images and sent them back to Earth as electrical signals. Orbiter took photographs, developed them on board, and then scanned them with a special photoelectric system - a method that, for all its complications and limitations, could produce images of exceptional quality. One Orbiter camera could resolve details as small as 3 feet from an altitude of 30 nautical miles. A sample complication exacted by this performance: because slow film had to be used (because of risk of radiation fogging), slow shutter speeds were also needed. This meant that, to prevent blurring from spacecraft motion, a velocity-height sensor had to insure that the film was moved a tiny, precise, and compensatory amount during the instant of exposure. |

The five Orbiters accomplished more than photo reconnaissance for Apollo. Sensors on board indicated that radiation levels found near the Moon would pose no dangerous threat to astronauts. An unexpected benefit came from careful analysis of spacecraft orbits, which showed small perturbations suggesting that the Moon was not gravitationally uniform, but had buried concentrations of mass. By discovering and defining these "mascons", the Orbiters made possible highly accurate landings and the precision rendezvous that would characterize Apollo flights. Once their work was finished, the Orbiters were deliberately crashed on the Moon, so that their radio transmitters would never interfere with later craft.

| Next |