Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

ARRANGING FOR SURVIVAL

The knot tightened in my stomach, and all regrets about not

landing on the Moon vanished. Now it was strictly a case of

survival.

The first thing we did, even before we discovered the oxygen

leak, was to try to close the hatch between the CM and the LM. We

reacted spontaneously, like submarine crews, closing the hatches

to limit the amount of flooding. First Jack and then I tried to

lock the reluctant hatch, but the stubborn lid wouldn't stay

shut! Exasperated, and realizing that we didn't have a cabin

leak, we strapped the hatch to the CM couch.

In retrospect, it was a good thing that we kept the tunnel

open, because Fred and I would soon have to make a quick trip to

the LM in our fight for survival. It is interesting to note that

days later, just before we jettisoned the LM, when the hatch had

to be closed and locked, Jack did it - easy as pie. That's the

kind of flight it was.

| | |

"There's one whole side of that spacecraft missing,"

said Lovell in astonishment. About five hours before

splashdown the service module was jettisoned

in a manner that would permit the astronauts

to assess its condition.

Until then, nobody realized the extent of the damage.

|

| | |

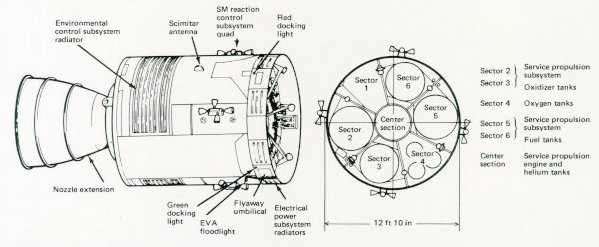

Vital stores of oxygen, water, propellant, and

power were lost when the side of the service

module blew off. The astronauts quickly moved

into the lunar module which had been provided

with independent supplies of these space

necessities for the landing on the Moon.

Years before, Apollo engineers had talked of

using the lunar module as a lifeboat.

|

The pressure in the No. 1 oxygen tank continued to drift

downward; passing 300 psi, now heading toward 200 psi. Months

later, after the accident investigation was complete, it was

determined that, when No. 2 tank blew up, it either ruptured a

line on the No. 1 tank, or caused one of the valves to leak. When

the pressure reached 200 psi, it was obvious that we were going

to lose all oxygen, which meant that the last fuel cell would

also die.

At 1 hour and 29 seconds after the bang, Jack Lousma, then

CapCom, said after instructions from Flight Director Glynn

Lunney: "It is slowly going to zero, and we are starting to think

about the LM lifeboat." Swigert replied, "That's what we have

been thinking about too."

| | |

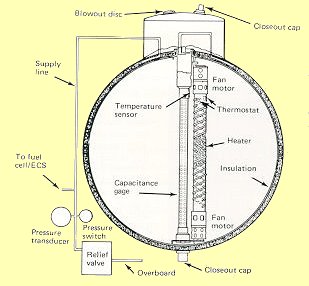

Oxygen tank No. 2 overheated and blew up because its

heater switches welded shut during excessive prelaunch

electric currents. Interior diagram (above)

of three-foot-tall oxygen tank No. 2 - whose

placement in bay 4 of SM is

indicated below - shows vertical heater

tube and quantity measurement tube.

Heater tube contains two 1800-rpm

motors to stir tank's 320 pounds of

liquid oxygen. Note thermostat at top.

Two switches were supposed to open

heater circuit when temperature reached 80° F,

but spacecraft power supply had been changed from

28 to 65 Vdc - while contractors and NASA

test teams nodded - so switches welded shut

and heater tube temperature probably reached 1000° F.

|

A lot has been written about using the LM as a lifeboat

after the CM has become disabled. There are documents to prove

that the lifeboat theory was discussed just before the Lunar

Orbit Rendezvous mode was chosen in 1962. Other references go

back to 1963, but by 1964 a study at the Manned Spacecraft Center

concluded: "The LM [as lifeboat] . . . was finally dropped,

because no single reasonable CSM failure could be identified that

would prohibit use of the SPS." Naturally, I'm glad that view

didn't prevail, and I'm thankful that by the time of Apollo 10,

the first lunar mission carrying the LM, the LM as a lifeboat was

again being discussed. Fred Haise, fortunately, held the

reputation as the top astronaut expert on the LM- after spending

fourteen months at the Grumman plant on Long Island, where the LM

was built.

Fred says: "I never heard of the LM being used in the sense

that we used it. We had procedures, and we had trained to use it

as a backup propulsion device, the rationale being that the thing

we were really covering was the failure of the command module's

main engine, the SPS engine. In that case, we would have used

combinations of the LM descent engine, and in some cases, for

some lunar aborts, the ascent engine as well. But we never really

thought and planned, and obviously, we didn't have the procedures

to cover a case where the command module would end up fully

powered down."

| | |

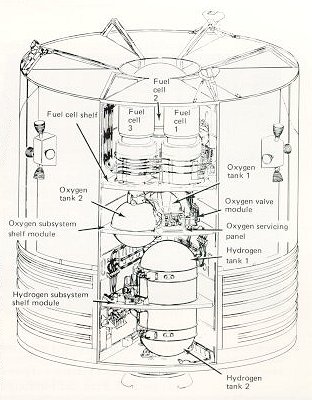

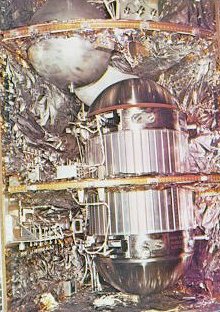

Top of Apollo 13's fuel tank No. 2 (bottom part is below shelf),

photographed before it left North American

Rockwell plant. Tank was originally installed

in Apollo 10's SM, but was removed for modification and in process

was dropped two inches (skin of tank is only 0.02 inch thick).

Then it was installed on Apollo 13 and certified,

despite test anomalies. In raging heat, it burst

and the explosion was ruinous to the SM.

|

|

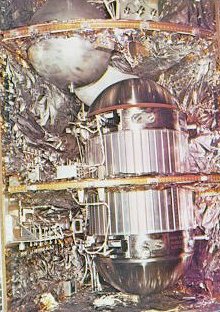

Nestled amid crinkled metal foil used for

thermal insulation, oxygen tank No. 2 was

mounted above and close to a

pair of hydrogen tanks in spacecraft bay.

|

To get Apollo 13 home would require a lot of innovation.

Most of the material written about our mission describes the

ground-based activities, and I certainly agree that without the

splendid people in Mission Control, and their backups, we'd still

be up there.

They faced a formidable task. Completely new procedures had

to be written and tested in the simulator before being passed up

to us. The navigation problem was also theirs; essentially how,

when, and in what attitude to burn the LM descent engine to

provide a quick return home. They were always aware of our

safety, as exemplified by the jury-rig fix of our environmental

system to reduce the carbon dioxide level.

However, I would be remiss not to state that it really was

the teamwork between the ground and flight crew that resulted in

a successful return. I was blessed with two shipmates who were

very knowledgeable about their spacecraft systems. and the

disabled service module forced me to relearn quickly how to

control spacecraft attitude from the LM, a task that became more

difficult when we turned off the attitude indicator.

|