Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

GEMINI PROGRAM

The Gemini program was designed to investigate in actual flight many of the

critical situations which we would face later in the voyage of Apollo. The spacecraft

carried an onboard propulsion system for maneuvering in Earth orbit. A guidance and

navigation system and a rendezvous radar were provided to permit astronauts to try

out various techniques of rendezvous and docking with an Agena target vehicle. After

docking, the astronauts could light off the Agena rocket for large changes in orbit,

simulating the entry-into-lunar-orbit and the return-to-Earth burns of Apollo. Gemini

was the first to use the controlled reentry system that was required for Apollo in

returning from the Moon. It had latches that could be opened and closed in space to

permit extravehicular activity by astronauts, and fuel cells similar in purpose to those

of Apollo to permit flights of long duration. The spacecraft was small by Apollo standards,

carrying only two men in close quarters. However, the Titan II launch vehicle,

which was the best available at that time, could not manage a larger payload.

| | |

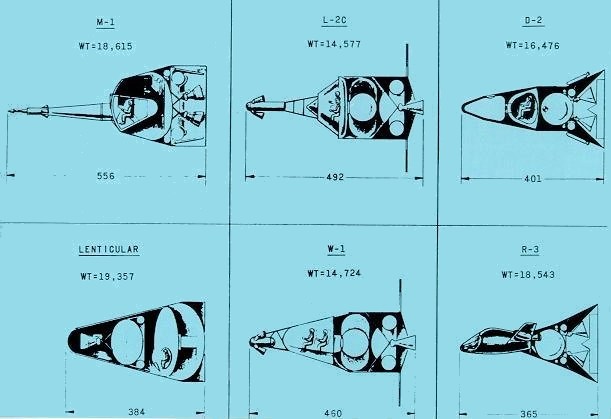

Early proposals for manned space vehicles varied

greatly in configuration and weight. In some, the men

within faced one way during launch and another during

reentry; in others, the vehicle was turned around,

not the seats. Different approaches to the problem of

escape from launching disaster were shown in these

six industrial proposals. Environmental control,

thermal and radiation shielding, and protection

against meteorite impact were all unknowns facing

early spacecraft designers.

|

| | |

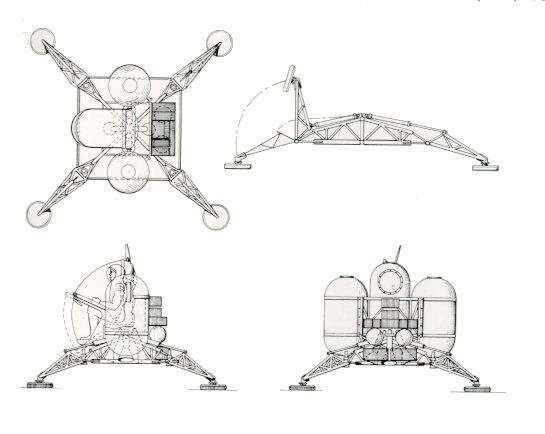

A one-man lunar lander weighing 5000 pounds was

envisioned as early as 1961 by a pair of Space Task

Group engineers, James A. Chamberlin and James T.

Ross, and here drawn by Harry A. Shoaf. It was seen

as part of a 35,000-pound payload that might be carried

by a post-Mercury spacecraft. The other extreme

in early ideas to send men to the Moon called for a

direct-ascent manned lunar vehicle weighing some

150,000 pounds. It would have been launched by

Nova, a giant booster capable (on paper) of

approximately 12 million pounds of thrust.

|

A total of 10 manned flights were made in the Gemini program between March

1965 and November 1966. They gave us nearly 2000 man-hours in space and developed

the rendezvous and docking techniques essential to Apollo. By burning the Agena

rockets after docking, we were able to go to altitudes of more than 800 nautical miles

and prove the feasibility of the precise space maneuvers essential to Apollo. Our first

experience in EVA was obtained with Gemini and difficulties here early in the program

paved the way for the smoothly working EVA systems used later on the Moon. The

Borman and Lovell flight, Gemini VII, showed us that durations up to two weeks were

possible without serious medical problems, and the later flights showed the importance

of neutral buoyancy training in preparation of zero-gravity operations outside the

spacecraft.

Gemini gave us the confidence we needed in complex space operations, and it

was during this period that Chris Kraft and his team really made spaceflight operational.

They devised superb techniques for flight management, and Mission Control

developed to where it was really ready for the complex Apollo missions. Chris Kraft,

Deke Slayton, head of the astronauts, and Dr. Berry, our head of Medical Operations,

learned to work together as a team. Finally, the success of these operations and the

high spaceflight activity kept public interest at a peak, giving our national leaders the

broad supporting interest and general approval that made it possible to press ahead

with a program of the scale of Apollo.

|

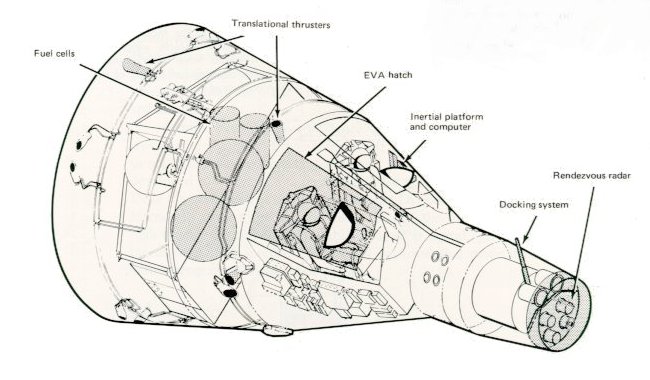

This Gemini spacecraft, in preparation in

the Pyrotechnical Installation Building at

the Cape, was to climb to a record altitude

of 853 miles in September 1966. It docked

in space with an Agena, and then used the

big Agena rocket for the energy needed

to reach the larger orbit. Gemini flights

provided priceless experience in the tricky

business of rendezvousing two craft in

space with the minimum expenditure of

energy. They also supplied practice at

docking and in extravehicular activity,

both needed for future Moon voyages.

Finally, they helped build up experience

with the mission-control system developing

on the ground to support manned spaceflight.

|

| | |

The two-man Gemini seemed capacious

after tiny Mercury but it was actually very

cramped. The astronauts rubbed elbows,

and the man in the right seat, returning

after EVA with his bulky spacesuit and

tether, had to jam himself in to close the

hatch over his head. |

|