Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

CHOOSING THE BUILDERS

How many prime contractors, we wondered, should NASA bring in for the development

of the Saturn V? Just one, or one per stage? How about the Instrument Unit

that was to house the rocket's inertial-guidance system, its digital computer, and an

assortment of radio command and telemetry functions? Who would do the overall

systems engineering and monitor the intricate interface between the huge rocket and

the complex propellant-loading and launching facilities at Cape Canaveral? Where

would the various stages be static-tested?

|

One of the J-2 engines that power the upper stages

of Saturn V. Liquid hydrogen, on its

way from the fuel turbopump, is used to cool

the walls of the thrust chamber regeneratively.

|

Understandably, the entire aerospace industry was attracted by both the financial

value and the technological challenge of Saturn V. To give the entire plum to a single

contractor would have left all others unhappy. More important, Saturn V needed the

very best engineering and management talent the industry could muster. By breaking

up the parcel into several pieces, more top people could be brought to bear on the

program.

| | |

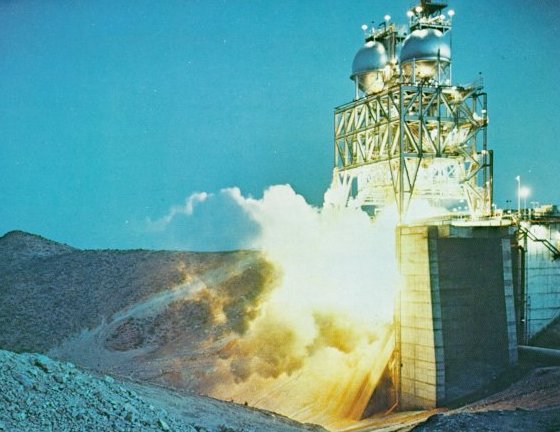

Thunder echoed in the mountains when a mighty

F-1 engine spoke out during qualification. At a remote high-thrust

test complex near Edwards, Calif.,

fuel and LOX were pumped in and tons of water cascaded

over the flame deflector while elaborate instrumentation

measured the behavior of each new engine.

It wasn't flightworthy if it didn't match specs.

|

The Boeing Company was the successful bidder on the first stage (S-IC); North

American Aviation won the second stage (S-11), and Douclas Aircraft fell heir to the

Saturn V's third stage (S-IVB). Systems engineering and overall responsibility for the

Saturn V development was assigned to the Marshall Space Flight Center. The

inertial-guidance system had emerged from a Marshall in-house development, and as it had to

be located close to other elements of the big rocket's central nervous system, it was only

logical to develop the Instrument Unit (IU) to house this electronic gear as a Marshall

in-house project. IU flight units were subsequently produced by IBM, which had

developed the launch-vehicle computer.

|

The first (S-IC) stage of the Saturn V launch vehicle being hoisted into the static test stand

at Marshall Space Flight Center. This was the "battleship," or developmental test version of the

stage, built heavily to permit repeated testing of flight-version working components. The first

three flight S-IC stages were assembled at MSFC and tested in this stand. The massively reinforced

construction of the 300-foot-tall stand was essential to withstand the 7.5 million pounds

of thrust developed by the stage's engines during static testing.

|

Uniquely tight procurement procedures introduced by NASA Administrator Jim

Webb made it possible to acquire billions of dollars' worth of exotic hardware and

facilities without overrunning initial cost estimates and without the slightest hint of

procurement irregularity. Before it could issue a request for bids, the contracting NASA

Center had to prepare a detailed procurement plan that required the Administrator's

personal approval, and that could not be changed thereafter. It had to include a point-scoring

system in which evaluation criteria - technical merits, cost, skill availability,

prior experience, etc. - were given specific weighting factors. Business and technical

criteria were evaluated by separate teams not permitted to know the other's rankings.

The total matrix was then assembled by a Source Evaluation Board that gave a complete

presentation of all bids and their scoring results to the three top men in the agency,

who themselves chose the winner. There was simply no room for arbitrariness or

irregularity in such a system.

|

The "pogo problem," a lengthwise

mode of vibration recognized in the

second Saturn V launch, was speedily

solved through mathematical analysis

supported by data collected in shake

tests. To supplement shake tests in

Marshall's Dynamic Test Tower, Boeing

quickly erected this tower for

special pressure tests at the Michoud

Assembly Facility.

|

The tremendous increase in contracts needed for the Saturn V program required

a reorganization of the Marshall Space Flight Center. Most of our resources had been

spent in-house, and our contracts had either been let to support contractors or to producers

of our developed products. Now 90 percent of our budget was spent in industry,

much of it on complicated assignments which included design, manufacture, and

testing. So on September 1, 1963, I announced that Marshall would henceforth consist

of two major elements, one to be called Research and Development Operations, the

other Industrial Operations. Most of my old R&D associates then became a sort of

architect's staff keeping an eye on the integrity of the structure called Saturn V, and the

other group funded and supervised the industrial contractors.

| | |

A test at the "Arm Farm". Just to

the man's left a skin section representing the S-11 stage is mounted to

the Random Motion/Lift-Off Simulator,

which can simulate at ground level

the swaying of the space vehicle in a

Florida storm. A duplicate of the

Mobile Launch Tower's S-11 Forward

Swingarm projects from the left, carrying the umbilicals that are connected

to the skin section.

|

That same year Dr. George Mueller had taken over as NASA's Associate Administrator

for Manned Space Flight. He brought with him Air Force Maj. Gen. Samuel

Phillips, who had served as program manager for Minuteman, and now became Apollo

Program Director at NASA Headquarters. Both men successfully shaped the three

NASA Centers involved in the lunar-landing program into a team. I was particularly

fortunate in that Sam Phillips persuaded his old friend and associate Col. (later Maj.

Gen.) Edwin O'Connor to assume the directorship of Marshall's Industrial Operations.

On September 7, 1961, NASA had taken over the Michoud Ordnance plant at

New Orleans. The cavernous plant - 46 acres under one roof - was assigned to

Chrysler and Boeing to set up production for the first stages of Saturn I and Saturn V. In

October 1961 an area of 13,350 acres in Hancock County, Miss., was acquired. Huge

test stands were erected there for the static testing, of Saturn V's first and second stages.

Shipment of the oversize stages between Huntsville, Michoud, the Mississippi Test

Facility, the two California contractors, and the Kennedy Space Center in Florida

required barges and seagoing ships. Soon Marshall found itself running a small fleet

that included the barges Palaemon, Orion, and Promise.

For shipments through the

Panama Canal we used the USNS Point Barrow and the SS Steel Executive.

For rapid transport we had two converted Stratocruisers at our disposal with the descriptive

names "Pregnant Guppy" and "Super Guppy". Their bulbous bodies could accommodate

cargo up to the size of an S-IVB stage.

|