Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

COMPLEX SUBSYSTEMS PERFORMED VITAL FUNCTIONS

At the heart of each spacecraft were its subsystems. "Subsystem" is space-age

jargon for a mechanical or electronic device that performs a specific function such as

providing oxygen, electric power, and even bathroom facilities. CSM and LM subsystems

performed similar functions, but differed in their design because each had to

be adapted to the peculiarities of the spacecraft and its environment.

Begin with the environmental control system - the life-support system for man

and his machine. It was a marvel of efficiency and reliability, with weight and volume

at a premium. A scuba diver uses a tank of air in 60 minutes; in Apollo an equivalent

amount of oxygen lasted 15 hours. Oxygen was not simply inhaled once and then

discarded: the exhaled gas was scrubbed to eliminate its CO2 recycled, and reused.

At the same time, its temperature was maintained at a comfortable level, moisture was

removed, and odors were eliminated. That's not all: the same life-support system also

maintained the cabin at the right pressure, provided hot and cold water, and a circulating

coolant to keep all the electronic gear at the proper temperature. (In the weightless

environment of space, there are no convective currents, and equipment must be cooled

by means of circulating fluids.) Because astronauts' lives depended on this systern,

most of the functions were provided with redundancy - and yet the entire unit was not

much bigger than a window air conditioner.

|

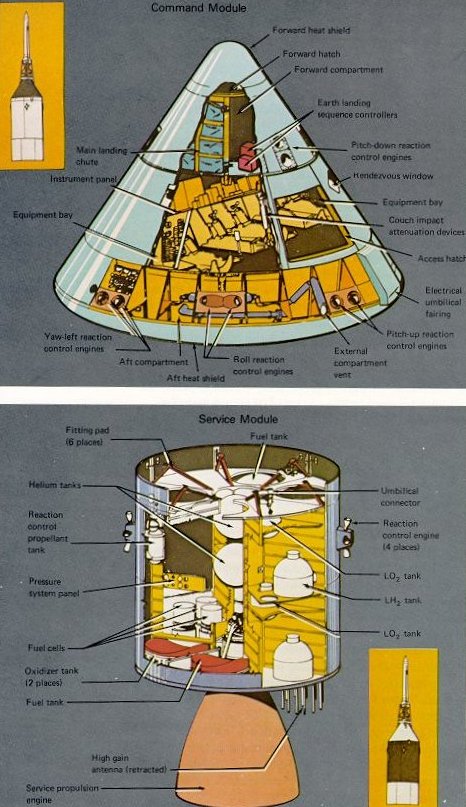

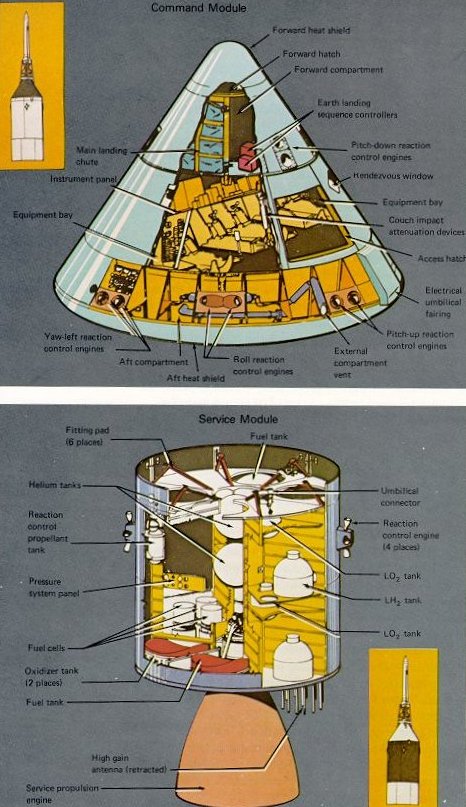

Above: Looking like a huge toy top

the conical command module

was crammed with some of

the most complex equipment

ever sent into space. The three

astronaut couches were surrounded by instrument panels,

navigation gear, radios, life-support systems, and small

engines to keep it stable during

reentry. The entire cone, 11

feet long and 13 feet in diameter, was protected by a

charring heat shield. The 6.5-ton CM was all that was

finally left of the 3000-ton

Saturn V stack that lifted oft

on the journey to the Moon.

Below: Packed with plumbing and

tanks, the service module was

the CM's constant companion

until just before reentry. So

all components not needed

during the last few minutes of

flight, and therefore requiring

no protection against reentry

heat, were transported in this

module. It carried oxygen for

most of the trip; fuel cells to

generate electricity (along

with the oxygen and hydrogen to run them);

small engines to control pitch, roll,

and yaw; and a large engine

to propel the spacecraft into -and out of- lunar orbit.

|

| | |

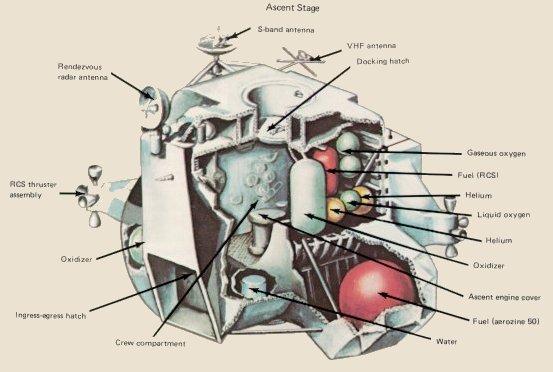

The lunar module was also a two-part

spacecraft. Its lower or descent stage had the landing

gear and engines and fuel

needed for the landing. When

the LM blasted off the Moon,

the descent stage served as

the launching pad for its

companion ascent stage,

which was also home for the

two explorers on the surface.

In function if not in looks the

LM was like the CM, full of

gear to communicate, navigate, and rendezvous. But it

also had its own propulsion

system, an engine to lift it off

the Moon and send it on a

course toward the command

module orbiting above.

|

How do you generate enough electric power to run a ship in space? In the CSM,

the answer was fuel cells; in the LM, storage batteries. Apollo fuel cells used oxygen

and hydrogen -stored as liquids at extremely cold temperatures- that when combined

chemically yielded electric power and, as a byproduct, water for drinking. (In early

flights the water contained entrapped bubbles of hydrogen, which caused the astronauts

no real harm but engendered major gastronomical discomfort. This led to loud complaints,

and the problem was finally solved by installing special diaphragms in the

system.) The fuel-cell power system was efficient, clean, and absolutely pollution-free.

Storing oxygen and hydrogen required new advances in leakproof insulated containers.

lf an Apollo hydrogen tank were filled with ice and placed in a room at 70° F, it

would take 8.5 years for the ice to melt. lf an automobile tire leaked at the same rate

as these tanks, it would take 30 million years to go flat.

"Houston, this is Tranquility." These words soon would be heard from another

world, coming from an astronaut walking on the Moon, relayed to the LM, then to a

tracking station in Australia or Spain or California, and on to Mission Control in

Houston with only two seconds' delay. Communications from the Moon were clearer

and certainly more reliable than they were from my home in Nassau Bay (a stone's

throw from the Manned Spacecraft Center) to downtown Houston. At the same time,

a tiny instrument would register a reading in the astronauts' life-support system, and

a few seconds later an engineer in Mission Control would see a variation in oxygen

pressure, or a doctor a change in heart rate; and around the world people would watch

on their home television sets. Bebind all of this would be the Apollo communications

system-designed to be the astronauts' life line back to Earth, to be compact and

lightweight, and yet to function with absolute reliability; an array of receivers,

transmitters, power supplies and antennas, all tuned to perfection, that allowed the men and

equipment on the ground to extend the capabilities of the astronauts and their ships.

(Later on, when the computer on Apollo 11's LM was overloaded during the critical

final seconds of the landing, it was this communications system that enabled a highly

skilled flight controller named Steve Bales to tell Neil Armstrong that it was safe to

disregard the overload alarms and to go ahead with the lunar landing.)

|

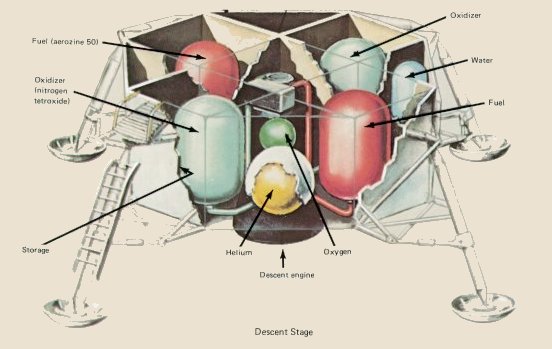

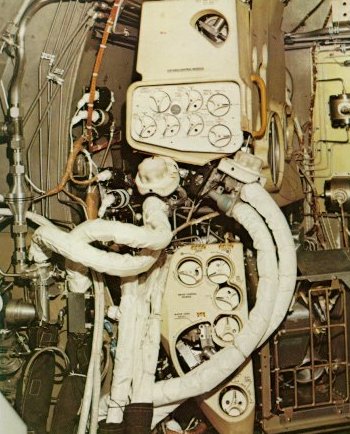

Like a plumber's dream, the LM's environmental control system nestled in

a corner of the ascent stage. Those

hoses provided pure oxygen to two astronauts at a pressure one-third that

of normal atmosphere, and at a comfortable temperature. The unit

recirculated the gas, scrubbed out CO2 and

moisture exhaled, and replenished oxygen as it was used up.

|

| | |

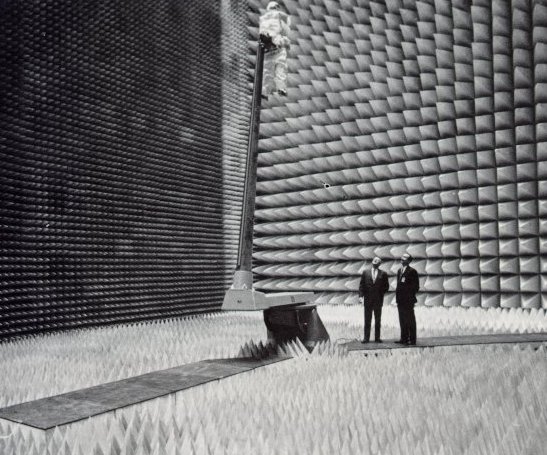

Sound is deadened and not an echo

can be heard in this anechoic test

chamber. Used to simulate reflection-free space, its floor, walls, and ceiling

are completely covered with foam

pyramids that absorb stray radiation,

so that an antenna's patterns can be

accurately measured. Here two NASA

engineers inspect a test setup of an

astronaut's backpack. Any interference between the astronaut and his

small antenna could be detected and

fixed before a real astronaut set foot

on the Moon.

|

If you had to single out one subsystem as being most important, most complex,

and yet most demanding in performance and precision, it would be Guidance and

Navigation. Its function: to guide Apollo across 250,000 miles of empty space; achieve

a precise orbit around the Moon; land on its surface within a few yards of a predesignated

spot; guide LM from the surface to a rendezvous in lunar orbit; guide the CM

to hit the Earth's atmosphere within a 27-mile "corridor" where the air was thick

enough to capture the spacecraft, and yet thin enough so as not to burn it up; and

finally land it close to a recovery ship in the middle of the Pacific Occan. Designed by

the Massachusetts Institute of Technology under Stark Draper's leadership, G&N consisted

of a miniature computer with an incredible amount of information in its memory;

an array of gyroscopes and accelerometers called the inertial-measurement unit; and

a space sextant to enable the navigator to take star sightings. Together they determined

precisely the spacecraft location between Earth and Moon, and how best to burn the

engines to correct the ship's course or to land at tbe right spot on the Moon with a

minimum expenditure of fuel. Precision was of utmost importance; there was no

margin for error, and there were no reserves for a missed approach to the Moon. In

Apollo 11, Eagle landed at Tranquility Base, after burning its descent engine for 12

minutes, with only 20 seconds of landing fuel remaining.

| | |

Like new Magellans, astronauts learned to navigate in space.

Here Walt Cunningham makes his

observations through a spacecraft window.

The tools of a space navigator included a sextant

to sight on the stars, a gyroscopically stabilized

platform to hold a constant reference in

space, and a computer to link the data and make

the most complex and precise calculations.

|

But the guidance system only told us where the spacecraft was and how to correct

its course. It provided the brain, while the propulsion system provided the brawn in

the form of rocket engines, propellant tanks, valves, and plumbing. There were 50

engines on the spacecraft, smaller but much more numerous than those on the combined

three stages of the Saturn that provided the launch toward the Moon. Most of

them - 16 on the LM, 16 on the SM, and 12 on the CM - furnished only 100 pounds

of thrust apiece; they oriented the craft in any desired direction just as an aircraft's

elevators, ailerons, and rudder control pitch, roll, and yaw.

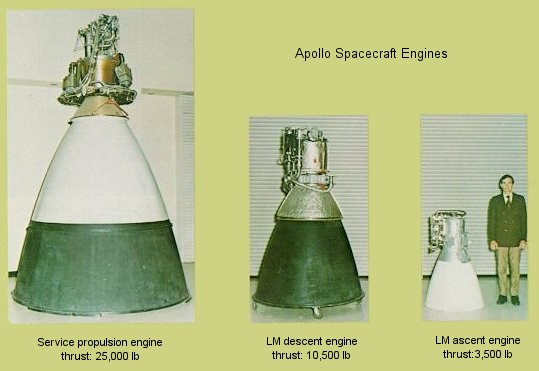

Three of the engines were much larger. On the service module a 20,500-pound-thrust

engine injected Apollo into lunar orbit, and later brought it back home; on the

LM there was a 10,500-pound-thrust engine for descent, and a 3500 pounder for

ascent. All three had to work: a failure would have stranded astronauts on the Moon

or in lunar orbit. They were designed with reliabillty as the number one consideration.

They used hypergolic propellants that burned spontaneously on contact and required

no spark plugs; the propellants were pressure-fed into the thrust chamber by bottled

helium, eliminating complex pumps; and the rocket nozzles were coated with an ablative

material for heat protection, avoiding the need for intricate cooling systems.

Three other engines could provide instant thrust at launch to get the spacecraft

away from the Saturn if it should inadvertently tumble or explode. The largest of these

produced 160,000 pounds of thrust, considerably more than the Redstone booster

which propelled Alan Shepard on America's first manned spaceflight. (Since we never

had an abort at launch, these three were never used.)

|

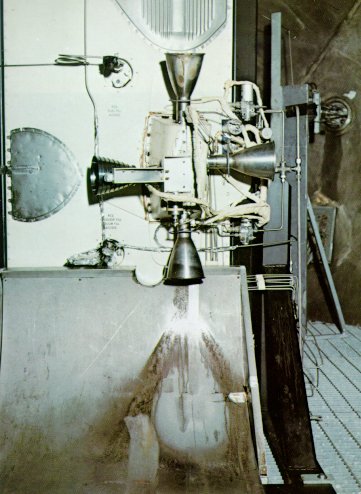

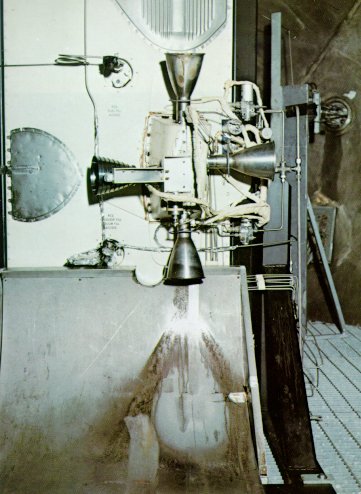

Because there is no air to deflect, a spacecraft

lacks rudders or ailerons. Instead, it has small

rocket engines to pitch it up or down, to yaw it

left or right, or to roll it about one axis. Sixteen

of them were mounted on the service module, in

"quads" of four. Here one quad is tested to make

sure that hot rocket exhaust will not burn a hole

in the spacecraft's thin skin.

|

| | |

Similar in shape but not size were the three big

engines aboard Apollo spacecraft. Two of them

had no backup, so they were designed to be the

most reliable engines ever built. lf the service-propulsion engine

failed in lunar orbit, three

astronauts would be unable to return home; if the

ascent engine failed on the Moon, it would leave

two explorers stranded. (A descent-engine failure

would not be as critical, because the ascent engine

might be used to save the crew members.)

|

There were other subsystems, each with its own intricacies of design, and, more

often than not, with its share of problems. There were displays and controls, backup

guidance systems, a lunar landing gear on the LM and an Earth landing system

(parachutes) on the CM, and a docking system designed with the precision of a Swiss watch,

yet strong enough to stop a freight car. There were also those things that fell between

the subsystems: wires, tubes, plumbing, valves, switches, relays, circuit breakers, and

explosive charges that started, stopped, ejected. separated, or otherwise activated

various sequences.

|