Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

A SHAKY START

The military rockets developed in the 1950s provided a basic tool with which it

became possible to send rudimentary spacecraft to the Moon. Both the Army and the

Air Force were quick to initiate efforts to be the first to the Moon with a manmade

object. (The Russians, as it proved, were equally quick, or quicker.) These first U.S.

projects, which were transferred in 1958 to the newly formed National Aeronautics and

Space Administration, consisted of four Air Force Thor-Able rockets, and two Army

Juno II rockets, each with tiny payloads, designed to measure radiation and magnetic

fields near the Moon and, in some cases, to obtain rudimentary pictures. NASA and

the Air Force then added three Atlas-Abie rockets, which could carry heavier payloads,

in an attempt to bolster these early high-risk efforts. Of these nine early missions

launched between August 1958 and December 1960, none really succeeded. Two

Thor-Able and all three Atlas-Able vehicles were destroyed during launch. One Thor-Able

and one of the Juno II's did not attain sufficient velocity to reach the Moon and

fell back to Earth. Two rockets were left.

|

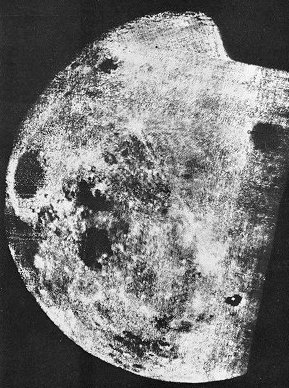

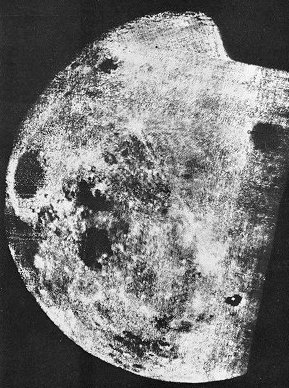

Mankind's first glimpse of the far side of the Moon came

in October 1959, provided by the Soviet spacecraft Luna

3. Although crude compared with later views, its pictures

showed a number of lunar features for the first time. One

of these was the crater Tsiolkovsky, named for the famed

Russian mathematician, which appears here in the lower

right as a small sea with an island in it. The images from

Luna 3 indicated that the Moon's far side lacked the large

mare areas an the side facing Earth.

|

The Soviets were also having problems. But on January 4, 1959, Luna 1, the first

space vehicle to reach escape velocity, passed the Moon within about 3700 miles and

went into orbit about the Sun. Two months later the United States repeated the feat

with the last Juno II, although its miss distance was 37,300 miles. A year later the last

Thor-Able payload flew past the Moon, but like its predecessors it yielded no new information

about the surface. On October 7, 1959, the Soviet Luna 3 became the first

spacecraft to photograph another celestial body, radioing to Earth crude pictures of the

previously unseen far side of the Moon. The Moon was not a "billboard in the sky"

with slatted back and props. Its far side was found to be cratered, as might be expected,

but unlike the front there were no large mare basins. The primitive imagery that Luna

3 returned was the first milepost in automated scientific exploration of other celestial

bodies.

|

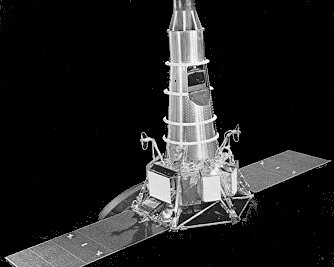

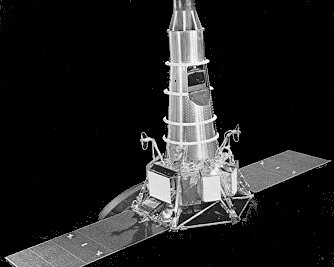

A sophisticated craft for its day, the

800-lb Ranger or its launch vehicle

failed in its first six tries. Then it behaved beautifully, returning thousands

of pictures in its last three flights, most

of them far superior to the best that

could be obtained from telescopes on

Earth. Rangers crashed on the Moon at

nonsurvivable velocity; their work was

done in the few short moments from

camera turn-on to impact.

|

|

Heading in toward Alphonsus, a

lunar crater of high scientific interest,

Ranger IX sent back 5814 pictures of

the surface before it crashed. The one

at left, taken several score miles away,

shows part of the crater floor and

slumped wall of Alphonsus, a rille

structure, and a varied population of

craters. Ranger pictures were exciting

in the wholly new details of the Moon

that they provided.

|

|

The last instant before it srnashed,

Ranger IX radioed back this historic

image, taken at a spacecraft altitude

of one-third mile about a quarter of a

second before impact. The area pictured is about 200 by 240 feet, and

details about one foot in size are

shown. The Ranger pictures revealed

nothing that discouraged Apollo planners, although they did indicate that

choosing an ideally smooth site for a

manned landing was not going to be an

easy task.

|

Undaunted by initial failures, and certainly spurred on by Soviet efforts, a NASA

team began to plan a long-term program of lunar exploration that would embody all

necessary ingredients for success. The National Academy of Sciences was enlisted to

help draw the university community into the effort. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a

California Institute of Technology affiliate that had been transferred from the Army

to NASA in 1958, was selected to carry out the program. JPL was already experienced

in rocketry and had participated in the Explorer and Pioneer IV projects.

|