Apollo Expeditions to the Moon

PREPARING FOR ALL EVENTUALITIES

Training was the name of the game, and they trained until it seemed the labors of

Hercules were child's play - how to make a tent out of your parachute in case you came

down in a desert; how to kill and eat a snake in the jungles of Panama; how to negotiate

volcanic lava in Hawaii. An Air Force C-135 flew endless parabolas so the

astronauts could have repeated half-minute doses of weightlessness. They wore weights

in huge water tanks in Houston and in Huntsville to get a feel of movement in zero and

one-sixth gravity.

|

| | |

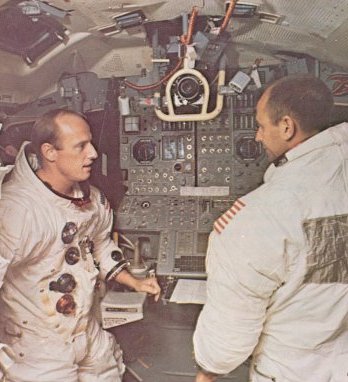

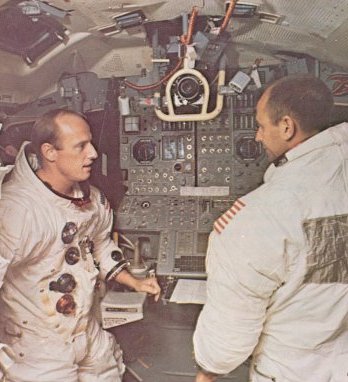

"The great train wreck" was John

Young's description of the contraption

beyond the console. At the top of the

stairs was a compartment that exactly

duplicated a command module control

area, with all switches and equipment.

Astronauts spent countless hours lying

on their backs in the CM simulator in

Houston. Panel lights came on and off,

gauges registered consumables, and

navigational data were displayed. Movie

screens replaced the spacecraft windows

and reflected whatever the computer

was thinking as a result of the combined

input from the console outside and

astronaut responses. Here the astronauts

practiced spacecraft rendezvous,

star alignment, and stabilizing a tumbling spacecraft.

The thousands of hours

of training in this collection of curiously

angled cubicles paid off. Many of the

problems that showed up in flight had

already been considered and it was

then merely a matter of keying in the

proper responses. At left (below), Charles Conrad

and Alan Bean in the LM simulator

at Cape Kennedy prepare to cope with

any possible malfunctions that the controllers at the console outside could

think up to test their familiarity with

the spacecraft and its systems.

|

|

Hair-raising was the device called the Lunar Landing Training Vehicle, a sort of

flying bedstead, which had a downward-pointing jet engine, gimbal-mounted and

computer-controlled to eliminate five-sixths

of gravity. In addition, it had attitude-controlling

thrusters to simulate the way the LM would act before touchdown on the

Moon. If the trainer ran out of fuel at altitude, or if it malfunctioned, the

Apollo commander - for he was the only one who had to fly the thing - had to

eject, which meant he was catapulted several hundred feet into the air before his

parachute opened. That was exactly what happened to Neil Armstrong a few months

before his Apollo 11 mission, when his bedstead started to tilt awry a hundred feet

above the ground. Armstrong shot into the air, then floated to safety; the machine

crashed and burned.

Dozens of training aids sharpened astronaut skills, but the most indispensable were

flight simulators, contraptions built around copies of CM and LM control areas and

complete to every last switch and warning light. Astronauts on prime status for the next

mission would climb in to flip switches and work controls. The simulator would be

linked to a computer programmed to give them practice too. What made it exciting

was that training supervisors could also get in the loop to introduce sneaky malfunctions,

full-bore emergencies, or imminent catastrophes to check on how fast and well

the crews and their controllers would cope. Surrounding the mockup spacecraft were

huge boxes for automatic movie and TV display of what astronauts would see in

flight: Earth, Moon, stars, another spacecraft coming in for docking. When John

Young first encountered a simulator he exclaimed "the great train wreck!". Hour

after weary hour the spacemen had to solve whatever problems the training crews

thought up and fed into the computer. The Apollo 11 crew calculated they spent 2000

hours in simulators between their selection in January and their flight in July 1969.

|

Neil Armstrong contemplates the distance

between the footpad and the lowest rung:

would he be able to get back up? (The

bottom of the ladder had to end high to

allow for shock-absorber compression of

the LM leg.) He decided he could do it.

Ascent proved no problem in reduced

lunar gravity.

|

|

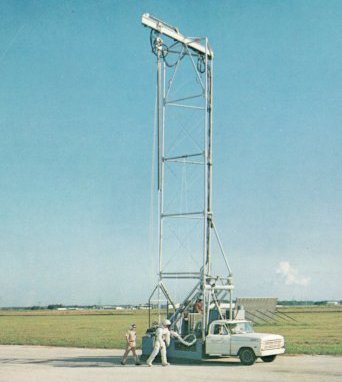

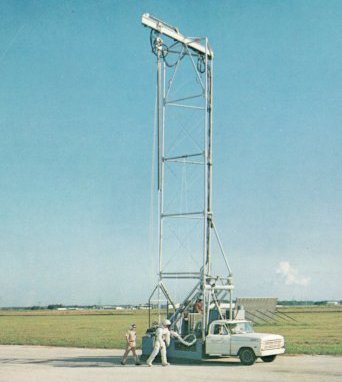

Preparing for the unknown was a challenge. How much work could be done by

a man within a pressurized (and hence

stiff-jointed) spacesuit? What effect would

the lesser lunar gravity have on his efforts?

This truck-borne hoist, adjusted to take out

five-sixths of his weight, gave preliminary

indications. It also previewed the loping

and kangaroo-hopping gaits that would

occur on the Moon. A different way to

simulate lunar gravity was also tried out;

see the rig here.

|

Some of this bone-cracking training was done in Houston but much of it at the

Cape, in Downey, Calif. (the CM), or Bethpage, Long Island (the LM). When the

astronauts were not training they were flying in their two-seater T-38 planes from one

place to the other, or doing aerobatics to sharpen their edge, or simply to unwind.

Their long absences proved a plague on their home lives, and there was hardly a man among

them who did not consider quitting the program at one time or another "to spend

some time with my family".

|