Chapter 11

Come Fly with Us

15 July 1975 - Launch

[317] At 5:50 a.m.,* Glynn Lunney entered the second floor Mission Operations Control Room (MOCR), located in the Mission Control Center-Houston (MCC-H). All smiles, with just traces of sleepiness in his eyes, he spoke to several of the men who were already on duty at their flight consoles. As he fitted his headset, Lunney nodded a good morning to R. Terry White, who for this shift was the "Voice of Apollo Control." Alex Tatistcheff, Lunney's interpreter, arrived at five past six, just as the Soviet launch complex was first shown on the television monitors and on the large eidophor picture screen in the MOCR. By 6:55 when the first televised public information release was transmitted from Moscow Mission Control Center (MCC-M), George Low and Chris Kraft had joined the growing number of people in the Houston control room.1

Reports from Baykonur indicated that the weather was perfect for the launch clear skies, light winds, and hot July sunshine. With the crew on board and 45 minutes remaining until lift-off, the ground team removed the semicircular halves of the service structure. Soyuz 19 sat poised for the launch. In Houston, Ross Lavroff interpreted the commentary as it was broadcast from MCC-M in Kaliningrad:

This is the Soviet Mission Control Center. Moscow time is 15 hours, 15 minutes. Everything is ready at the Cosmodrome for the launch of the Soviet spacecraft Soyuz. Five minutes remaining for launch. Onboard systems are now under onboard control. The right control board . . . opposite the commander's couch is now turned on. The cosmonauts have strapped themselves in and reported that they are ready. They have lowered their face plates. The key for launch has been inserted. . . . The crew is ready for launch.2

Five minutes later, the fueling tower was removed, and the command was given for launch. "Ignition. The engines are powered up. The launch; [318] the booster is off. Moscow time 15 hours, 20 minutes, 10 seconds. The flight is proceeding normally." At 120 seconds into the flight, the strap-on booster units of the first stage were separated. Then at 160 seconds, the emergency abort system was jettisoned, followed by the separation of the launch shroud and the firing of the second-stage engines. Third-stage ignition took place at 270 seconds, orbital insertion at 530 seconds. The third stage was shut down, and the antennas and solar panels were extended. Kubasov asked the ground, "How do you read?" MCC-M responded that they heard them well. The initial orbital parameters were 220.8 by 185.07 kilometers, at the desired inclination of 51.80°, while the period of the first orbit was 88.6 minutes. There were smiles in Moscow and in Houston.3

Max Faget, who was seated in the viewing room overlooking the MOCR, expressed the feeling of most of the American flight team. "It's our turn to hit the ball. Now we've got to get into orbit." Early evening at Baykonur was mid-afternoon in Moscow and early morning in Florida and Texas. While the American crew slept, Chet Lee, Launch Director Walt Kapryan, and Kennedy Space Center (KSC) Director Lee Scherer monitored the continuing preparation of SA-210. At the time of the Soyuz lift-off, liquid oxygen was flowing into the tanks of the Apollo launch vehicle at a fast fill rate of 4,543 liters per minute. After the U.S.S.R. launch, Lee, Kapryan, and Scherer got a briefing on the predicted weather conditions for the afternoon - there were thunderstorms in the vicinity of the Cape, but they were not expected to affect the American lift-off. In Houston, Lunney called Professor Bushuyev to congratulate him on the success of the Soyuz launch and to advise him that the countdown was proceeding on schedule with the best weather forecast in months. Bushuyev reported in turn that the orbit of Soyuz was within 2 or 3 kilometers of the desired figures.4

Stafford, Slayton, and Brand were awakened at 9:10. While they were having their final medical examination, the team that assists the crew at the launch site set out for the spacecraft. Following their visit with the doctors, the astronauts sat down to the traditional pre-flight breakfast of steak and scrambled eggs. As they ate, they watched a video replay of the Soyuz launch. Robert Crippen, the Backup Command Module Pilot, meanwhile began the final preparation of the command and service module (CSM) cockpit in anticipation of the crew's arrival. Once they completed their breakfast, the three men went to the suit room in the Manned Spacecraft Operations Building and donned their space suits. At 11:37, accompanied by John Young, Chief of the Astronaut Office, they rode down the elevator and boarded their van for the 25-minute ride to the launch pad.5

With the assistance of their suit technicians, the crew arrived at Pad 39B, where they made their way by elevator to the 100-meter level of the [319] mobile launch tower. Once there, they crossed over swing arm number 9 and entered the White Room surrounding the spacecraft. Stafford was the first into the cockpit, where he moved into the left couch, assisted from the inside by Crippen, who also connected Stafford's electrical, oxygen, and communications umbilicals. Slayton was next, and Crippen went through the same procedures after he was seated in the right-hand couch. Brand was last. When Crippen completed his check of Brand's fittings, he removed the protective covering from the crewman's helmet, as he had for the other two. At 12:02, Stafford called to the test conductor Clarence Chauvin, "Looks like it's a good day to fly."6

Crippen slid down under the center couch and crawled out the hatch above Brand's head. After some additional checks, the CSM hatch was closed at approximately 12:22. As the first live launch pad color television pictures of the interior of the CSM were broadcast to the world, the crew began to run through the final checklist. Stafford asked Karol "Bo" Bobko, the Spacecraft Communicator (CapCom) at 1.10, "Are you giving us the countdown in English or Russian today?" Bobko responded, "Oh, I figured I'd give it in English." In Moscow, the Soviet flight director was reminding Leonov and Kubasov that the Apollo lift-off was set for 10:50 Moscow time (2:50 CDT). At T minus 7 minutes, 52 seconds, the Apollo crewmembers finished their checkout of some 556 switches, 40 event indicators, and 71 lights on the console. Stafford told Bobko to tell Soyuz to get ready for them. "We'll be up there shortly."7

After the final minutes of waiting, at 2:49:50, the now famous count backwards from 10 began. "10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, engine sequence start, 1, 0, launch. . . . We have liftoff. Moving out, clear the tower." Above the roar of the first-stage engines, Stafford reported that the ride had been a little shaky at lift-off, but now it was "smooth as silk." Fifty seconds into the flight, the acceleration force equaled 2 gs, twice the gravitational force normally experienced on earth. At 124 seconds, the crewmen were experiencing 4 gs as they dropped off the first stage and continued their journey under the power of the S-IVB stage. Fifty-two seconds later, they jettisoned the launch escape tower, and Stafford remarked, "Tower jett. There she goes! . . . Adios. . . . At 4:40, back to one g acceleration and looking good."

- Dick Truly, CapCom:

- Apollo, Houston. At 5 minutes you're GO.

- Stafford:

- Roger. 5 minutes. Looks good onboard, Dick. And we've got a beautiful sight.

- Truly:

- Roger. Wish I could see it.

- Stafford:

- Roger.

- Slayton:

- Man, I tell you, this is worth waiting 16 years for.

- [320] Brand:

- Got a beautiful ocean out . . . here, Dick.

- Truly:

- Roger, I believe all that.

- Stafford:

- Okay, at 5:30, onboard trajectory looks beautiful.

- Truly:

- Roger. Concur, Tom. You're right on the money.8

On the ground, Ed Smith and R. H. Dietz with grins on their faces echoed the same thoughts when they said, "We've got a ball game!" The rendezvous chase was on. Apollo had achieved orbital insertion at 2:59:55.5 central daylight time. Brand exclaimed, "Miy nakhoditsya na orbite!"**

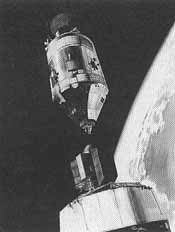

Stafford notified Houston at 3:55 p.m. that the crew was preparing to execute the transposition, docking, and extraction maneuver in 2 minutes. As a preliminary to removing the docking module (DM) from the spacecraft lunar module adapter (SLA) truss assembly, the CSM was separated from the S-IVB stage, and as the CSM moved away from the adapter section, the panels of the SLA were explosively jettisoned. In bringing the spacecraft about to face the docking module, the crew encountered its first minor problem of the flight. When Stafford looked through his alignment sight (COAS) at the Saturn IVB and docking module, the attitude was such that all he could see was the glare from the sunlit earth. At first he thought that the light illuminating the cross hairs in his sight had burned out. But when he put his hand in front of the COAS, Stafford reported that he could see the green reticle. Swearing under his breath, he knew that he would just have to wait until the two craft were positioned differently. Stafford moved the CSM toward the S-IVB and docking module until about only 10 meters separated them. Watching the stand-off cross on the docking module truss in the S-IVB stage, the Apollo crew assumed a stationkeeping status. Slowly the target vehicle appeared to move toward the earth's horizon. Stafford squinted and leaned his head to one side so he could see the reticle. "Finally when I got it in line," he later recounted, "I could just tell my general attitude and moved in." Despite the problems, Stafford's docking was perfect. He had aligned the two spacecraft to within a hundredth of a degree, the best alignment ever achieved with the Apollo docking system. By the time he had lined up his target, Apollo had passed out of radio contact with the ground.9

When Apollo re-established communications over Rosman, North Carolina, Stafford told Truly that they had achieved a real hard docking with the DM; all hatches were locked. The commander was happy to have this first docking completed. He later recalled that given the past problems with the Apollo probe and drogue, he had really been "sweating out" this exercise. Once it was over, he looked forward to meeting Soyuz. The new [321] docking mechanism was a pilot's dream, and he knew that he could fly it in for a smooth docking.10

During a subsequent 5-minute pass over the tracking ship USNS Vanguard, the crewmembers advised Houston that they had completed the extraction of the docking module. The spacecraft, configured as it would be for the meeting with the Soviet craft, was now in an orbit 173.3 by 154.7 kilometers with an orbital period of 87 minutes, 39 seconds, and an orbital velocity of 7,820 meters per second. Additional maneuvers would bring Apollo and Soyuz into the proper orbital relationship for rendezvous. Apollo's orbit was circularized at 167.4 by 164.7 kilometers at 6:35. From this orbit, the first Apollo phasing maneuver was executed at 8:28 to provide the proper catch-up rate, so that docking with Soyuz could occur on the 36th Soviet revolution. This 20.5-meter-per-second change placed Apollo in a 233- by 169-kilometer path. The next phase and plane correction maneuver of 2.7 meters per second was scheduled for the 16th revolution.11

In the midst of this precision flying, there were some lighter moments. At 6:10, Brand asked Truly to tell the launch crew at the Cape that they permitted a stowaway to board the spacecraft. "We found a super Florida mosquito flying around here a few minutes ago." Slayton said that he planned to feed it to the fish that they were carrying onboard if he could catch it, and Brand wanted to bring it back and give it astronaut wings.*** These transmissions were conducted through the ATS 6 satellite. While that particular communications satellite had been an unknown quantity throughout much of the mission planning, it was working very satisfactorily.

Placed in a geosynchronous orbit at 42,596 kilometers on 30 May 1974, ATS 6 had remained at a fixed point over the Galapagos Islands, permitting educational television transmissions to remote areas at relatively low costs. Following transmission experiments to Appalachia, the Rocky Mountains, and Alaska, the satellite on command from the ground moved to a new position over Africa, where it was to be used for a year-long educational experiment in India. It reached its present location, 35° east longitude on the equator, on 2 July, in time for the ASTP team to borrow its communications channels for the joint flight. Broadcasting through the spacecraft tracking and data network station at Buitrago, Spain, the Apollo crew and the team in Houston were able to talk and transmit data for 55 minutes of each 87-minute revolution. This three-fold increase in communications, impossible without ATS 6, made all the hard work and worry about its success worthwhile.12

Later in the evening, after a cabin overheating problem had been solved, Brand asked Karol Bobko, who had relieved Truly as CapCom, about the status of Soyuz.

|

|

|

|

Cosmonauts Alexei Leonov and Valeriy Kubasov (above) speak to reporters, then board their spacecraft for the launch and flight to position for rendezvous by Apollo. Below [left],the launch of their craft, Soyuz 19. |

|

|

|

|

With Soyuz successfully in orbit, Astronauts Vance Brand and Tom Stafford, (above, left) followed by Deke Slayton, arrive at the 100-meter level of the Saturn launch tower where their Apollo spacecraft awaits them. Final countdown is smooth, and the launch (right) is on time.

| |

|

|

|

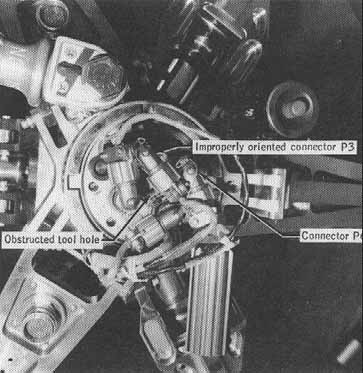

Once in orbit, the Apollo spacecraft separated from the S-IVB stage, then doubled back to dock with the docking module (DM) poised on the S-IVB (watercolor conception by Paul Field). After collecting the DM, Apollo fired up for rendezvous with Soyuz. The first problem of the flight occurred when Brand found he could not remove the docking probe from the tunnel entrance to the DM. Troubleshooters found that an improperly installed pyrotechnic connector (shown in this Rockwell photo taken before acceptance of the probe) had eluded Rockwell and NASA inspectors. |

[324] Bobko reported that Leonov and Kubasov were asleep and that to this point in the flight their only problem was a television camera that refused to work. He told Vance that they had tried without success to repair it but they planned to work on it some more after their sleep period. Apollo meal time arrived at 10:06, and Slayton coined a new space phrase for eating when he indicated to Houston that he and his crewmates were in the "food intake mode."13

A problem later that night, however, caused some concern both on the ground and in the spacecraft. Bobko had wished the crew good night in Russian, and they were supposed to be bedding down for a rest period, when at 22 minutes past midnight Stafford called to the ground. Brand had attempted to remove the probe assembly from the tunnel between the CSM and the DM so that he could open the hatch and store overnight a freezer**** in the passageway, but he found that he could not insert the tool that unlocked and collapsed the probe. Brand went on to explain the difficulty:

- Brand:

- Okay, Bo. Everything in the probe removal checklist on the cue card . . . has been going great up through step 11. Step 12 is "Capture latch release, tool 7." You insert it in the pyro cover. You turn it 180 degrees clockwise to release the capture latches. Well, here's where the problem is, and let me explain it to you. . . . do you have somebody there that knows the probe that can listen?

- Bobko:

- Roger. Go ahead.

- Brand:

- Okay, as I look in the back of the . . . pyro cover, I'm looking with my flashlight through the hole where I insert this tool, and there's something behind the pyro cover that's preventing me from putting this tool all the way in. . . . it's actually one of the pyro connectors. . . . this tool has to go down through the pyro cover in between . . . some pyro connectors. But one of these pyro connectors has rotated such that it's in the way. . . .14

Neil B. Hutchinson, flight director at the time the probe problem was discovered, later told press representatives that the ground team and the crew had discussed the difficulty for about 18 minutes. Their first decision had been to forget transferring the freezer into the tunnel and just have the crew close the hatch and go to sleep. But when Brand tried to close the hatch, he discovered that the partially removed probe assembly prevented him from doing so. Since the three men were already past their sleep time and the open hatch did not pose a hazard, the two teams ground and [325] space-agreed to postpone any further work on the probe until morning. As a precaution, the crew raised by a very slight amount the cabin pressure, which provided additional oxygen to compensate for the nitrogen that was boiling off the freezer. The crew went to sleep, and Hutchinson went to a 3:15 a.m. news briefing.15

In his explanation, the flight director indicated that the problem was not serious, just an annoyance. In the morning, the crew would have to run back through the 11 steps to re-engage the probe in its fully locked position. Then one of the men would have to remove the pyro cover, straighten out the misaligned pyro cap, go through the 11 disassembly steps, and on the 12th insert the key and unlock the capture latches. Afterwards the removal of the probe would follow according to the original plan. When asked if this was the same type of problem encountered in Apollo 14, Hutchinson answered that although this was the same probe assembly as that used in Apollo 14, the difficulty was an entirely different one.16 Everyone had to wait until morning to determine if the solution would be as simple as anticipated.

* Unless otherwise indicated, all times given are central daylight (CDT) or Soyuz, ground elapsed time (SGET). For Moscow time add 8 hours to CDT; for Greenwich mean time (GMT) add 5 hours to CDT.

*** After flying about for several hours, the mosquito was never seen again. Apparently, it died in the reduced pressure pure oxygen of the CSM.

**** The cryogenic freezer for the electrophoresis experiment was cooled by liquid nitrogen. Since it released nitrogen into the cabin, the flight plan called for it to be stored in the DM-CSM tunnel overnight.

1. Except where indicated, the account of the flight is based upon notes taken by Edward C. Ezell and Linda N. Ezell during the mission.

2. ASTP mission commentary transcript, MC 8/2 [mission commentary tape #8, p. 2], 15 July 1975.

3. ASTP mission commentary transcript, MC 9/1-2 and MC 10/1, 15 July 1975.

4. ASTP mission commentary transcript, MC 12/1-2, 15 July 1975.

5. ASTP mission commentary transcript, MC 26/1 and MC 33/1, 15 July 1975.

6. ASTP mission commentary transcript, MC 34/1, MC 32/1, MC 36/1, and MC 37/1-3, 15 July 1975.

7. ASTP mission commentary transcript, MC 42/1, SR 6/1 [Soviet mission commentary tape #6, p. 1] and MC 51/1, 15 July 1975.

8. NASA, JSC, Test Division, Program Operations Office, "ASTP Technical Air-to-Ground Voice Transcription," JSC-09815, July 1975, pp. 3-4. In NASA, JSC, Crew Training and Procedures Division Training Office, "ASTP Technical Crew Debriefing," JSC-09823, 8 Aug. 1975, pp. 3-1 through 3-2, the crew noted once again considerable longitudinal oscillation during the operation of the first stage.

9. Program Operation Office, "ASTP Technical Air-to-Ground Voice Transcription," p. 10; interview, Thomas P. Stafford-Ezell, 6 Apr. 1976; and NASA, JSC, "Apollo Soyuz Mission Evaluation Report," JSC-1067, Dec. 1975, pp. 10-1 and 10-2.

10. Interview, Stafford-Ezell, 6 Apr. 1976.

11. NASA, JSC, "Apollo Soyuz Mission Evaluation Report," JSC-10607, Oct. 1975, p. 3-1.

12. Program Operations Office, "ASTP Technical Air-to-Ground Voice Transcription," pp. 18-19; and [NASA News Release], Apollo News Center, JSC, "ASTP Change-of-Shift Debriefing," 15 July 1975. For further information on ATS 6, see NASA, Applications Technology Satellite-6 (ATS-6) [NASA Facts Series] (Washington, 1975); NASA News Release, HQ, 75-194, "ATS-6 Now on Station in View of India - Anomaly Being Studied," 2 July 1975; "ATS-6: Extra Special Satellite," Rendezvous [Textron/Bell, Aerospace Division] (Summer, 1974), pp. 8-11; and NASA, JSC, "Apollo Soyuz Mission Evaluation Report," JSC-10607, Oct. 1975, pp. 11-2 through 11-6.

13. Program Operations Office, "ASTP Technical Air-to-Ground Voice Transcription," pp. 46-47.

15. Ibid,. pp.60-63; and [NASA News Release], Apollo News Center, JSC, "ASTP Change-of-Shift Debriefing," 16 July 1975.

16. [NASA News Release],

Apollo News Center, JSC, "ASTP Change-of-Shift Debriefing," 16 July

1975; and NASA, MSC, Mission Evaluation Team, "Apollo 14 Mission

Anomaly Report No. 1, Failure to Achieve Docking Probe Capture Latch

Engagement," MSC 05101, Oct. 1971.

Next