18 July - Transfers

Awakened by "Midnight in Moscow," the Americans began their fourth work day in orbit at 2:00 a.m. Houston time. While the crews had slept, the two ground teams in Houston led by Walt Guy and V. K. Novikov had been watching the pressure levels of both ships and had conferred about the leak between the hatches. They had concluded that after the two hatches were closed and the pressure had been reduced to 260 millimeters the gases trapped between them heated up. The pressure sensing devices could not distinguish between the expanding gases and a leak. Neil Hutchinson commented on working with Soviet Flight Director Vadim Kravets, whom he had never met:

the hatch integrity check . . . involved me getting on the loop and talking to my counterpart who happened to be Kravets . . . the answers were all forthcoming in a timely fashion and very professionally done. . . . I think the one thing, as I sit back and look at it now that makes me wonder; I wish there was another one of these flights. We've gone to all this trouble to learn how to work with those people. It's like going to the moon once and never going back. 90 per cent of the battle is over with . . . getting all the firsts done. . . . I could run another Apollo Soyuz or another joint anything with a heck of a lot less fuss than it took to get this one going.33

Though some of the worry in both Houston and Moscow had been in vain, the two teams had confirmed that they could work together in analyzing an unforeseen problem.

With breakfast behind them and their early morning activities completed, Kubasov and Brand conducted a broadcast session from "your Soviet American TV center in space," as Kubasov called it. In giving his tour of Soyuz, the Soviet flight engineer pointed out what various instruments were for and televised a picture of Brand in "the kitchen" (the food preparation station) warming up lunch. Stafford reciprocated by giving Leonov and the Soviet viewers a Russian language tour of the command module. Despite some problems with communications to the ground, the space television production was just one more unique aspect of the joint mission. Appearing casually simple from the perspective of the home viewer, these broadcasts had required hours of negotiation and planning, just as all other aspects of the flight had. Soviet viewers were particularly enthralled by the live coverage of the mission, but many Americans seemed to accept shows from 225 kilometers up as commonplace.34

[333] Kubasov later gave an English language travelogue as the two craft passed over the U.S.S.R. "Dear American TV people," he began. "It would be wrong to ask which country's more beautiful. It would be right to say there is nothing more beautiful than our blue planet." After explaining that he would be giving a description of "what flows below the spacecraft," Kubasov continued:

Our spacecraft, Soyuz, is approaching the USSR territory. Our country occupies one-sixth of the Earth's surface. Its population is over 250 million people. It consists of 15 Union Republics. The biggest is the Russian Federal Republic with the population of 135 million people. . . . At the moment we are flying over the place where Volgograd city is. It was called Stalingrad before. In winter 1942-43, German fascist troops were defeated by the Soviet Army here. . . .

With the television camera still trained out the port of the orbital module, Leonov continued to describe the panorama. In the command module with Stafford and Slayton, the Soviet commander spoke of the Ural Mountains, and he pointed out the area below in Kazakhstan from which they had been launched three days before. Toward the end of the 10-minute commentary, Brand added some remarks about the countryside he could see from his vantage point and concluded, "as you can tell, Soviets very much remember the war 30 years ago. Fortunately, we've come a long way since then. . . ."35

Fifteen minutes later at about 8:20, Brand and Kubasov began filming some science demonstrations that could later be used in science classrooms back on earth to demonstrate the effects of zero gravity on various items. Originally proposed by Marshall Space Flight Center, Kubasov became very enthusiastic about the idea of such demonstrations, which were similar in concept to those filmed during Skylab. As a result, he suggested simple illustrations of basic principles of physics, such as the gyroscope, to be recorded during the flight. Brand narrated the film in English, and Kubasov gave the Russian commentary. Literally nowhere on earth could a classroom instructor duplicate the experiments, not to mention having such celebrities give the explanations.

During this second transfer, Brand had lunched in Soyuz and Leonov in Apollo. At 10:43, Brand returned to Apollo, and Stafford and Leonov moved into Soyuz. Kubasov then transferred into the command module in this exacting cosmic ballet. With each movement of the crewmembers, the atmospheric composition of Soyuz had to be checked to make certain that not too much nitrogen had been removed. Once everyone was in place, the hatches between the orbital and docking modules were closed as a further step toward maintaining the proper cabin atmospheres. The highlight of the third transfer - the space-to-ground press conference - was about to begin.

[334] 17-19 July 1975, Soyuz and Apollo Meet in Space

|

|

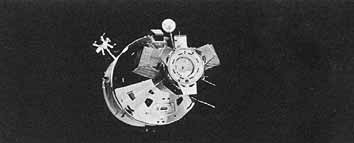

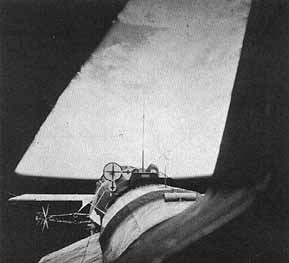

Left, Soyuz waits as Apollo (right) maneuvers closer (below) and docks. In the docked position the view out Apollo's window is along part of the docking module to the spherical bulk of Soyuz, one of whose solar cell arrays extends out parallel to the white earth horizon. |

|

| ||

| ||

|

|

| |

|

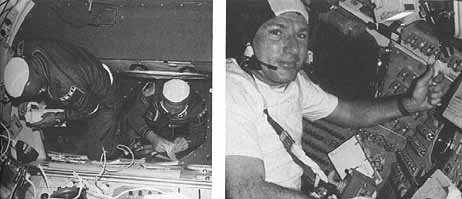

Above left, Cosmonaut Leonov and Astronaut Stafford meet in the docking module; above a cutaway drawing of the two spacecraft in docked position; above right, Leonov displays his sketch of Stafford; center, Stafford snaps photo of himself, Leonov, and Slayton literally putting their heads together; below, left, in the hatchway between the Soyuz orbital module and the descent module, Kubasov is at work as Leonov checks the flight plan; below, right, Brand monitors the Apollo controls while his fellow crewmen visit Soyuz. | ||

| ||

| ||

[336]

|

On the ground in the control center in Houston during the Apollo-Soyuz flight, Cernan, Lunney, and Tatistcheff follow mission progress (left); in Moscow, Viktor Legostayev (foreground) and Alexei Yeliseyev do the same (Soviet Academy of Sciences photo). |

|

| ||

|

|

Other mission activities in Houston: Soviet technical specialists V. V. Illarionov (above, foreground), O. I. Babkov, and V. I. Staroverov monitor the flight plan; at left, Working Group Chairmen Guy (foreground), White, and Dietz jointly monitor the mission; below, Robert Shafer (center) sits listening to Harold Stall discuss the mission's TV; bottom left, Administrator Fletcher directs Soviet Ambassador Anatoliy Dobrinin's attending to the large eidophor display screen, while technical assistant Leonard Nicholson stands by; bottom right, cheering the Apollo splashdown are controllers Don Ruddy (left), Frank Littleton, M. P. Frank, Neil Hutchinson, and Gene Kranz. | |

|

|

| |

| ||

[337] Having collected questions in advance from news people in Moscow and Houston, Valeriy Vasil'yevich Illarionov of the visiting specialists team and Karol Bobko read the questions to the crews from Houston. The queries and the responses were friendly, in the spirit of the mission. Stafford began by saying that it had been a very rewarding two days in space. He felt that the success of the mission was the result of "the determination, the cooperation, and the efforts by the governments of the two countries, by the managers, engineers, and all the workers involved." When he first opened the hatch to greet Leonov and Kubasov, he had a couple of thoughts that he was unable to express at the time. He believed that when they opened those hatches in space, they were opening the possibility of a new era on earth. "I would have said," in Russian, "we were opening back on Earth a new era in the history of man." He noted that just how far that new era would go would depend upon "the determination, the commitments, and the faith of both countries and of the world." The "climate of detente and a developing cooperation between our countries" has made this mission possible, Leonov added.

Because of his participation in the first space welding in 1969, Kubasov was asked about materials processing in space. Kubasov believed that one of the future benefits of space programs would be the development of better and different alloys resulting from space processing. "It seems to me that the time will come when space will have whole plants, factories, for the production of new materials and new substances with new qualities, which could be . . . made only in space." Linked to that question was one from Moscow addressed to Stafford about the justification of spending money on space programs when there were so many problems in the world that needed solving.

Stafford noted that this was not a new question. He certainly believed that the costs would be repaid by the long term benefits. Science and applications were the likely areas of payoff, but the uplift to the human spirit was also implicit in his words and those of his colleagues. All the men agreed that they preferred news of peace and tranquility, and Kubasov especially hoped that all children would have a future filled with peace, so that they would never have to know what it was like to lose parents or loved ones in a war. On a lighter note, when a Soviet reporter asked Leonov to transmit a sketch "that would depict the meaning, the essence of the joint mission," Leonov and Stafford held up two flags, one from the United States and one from the Soviet Union - although backwards, the message was clear enough. Leonov then went on to show the television audience a number of sketches that he had drawn - "Here's a whole cosmic portrait gallery."

The best lines of the press conference came later. When asked how he liked the American food, Leonov diplomatically answered, "I liked the way it was prepared, its freshness."

[338] But as an old philosopher says, the best part of a good dinner is not what you eat, but with whom you eat. Today I have dinner together with my very good friends Tom Stafford and Deke Slayton because it was the best part of my dinner.

Slayton was asked how the experience of space flight compared to all the stories he had been told over the years. He said that he did not think he had discovered anything new.

We've had the same kind of problems up here that people have complained about since MR-3. . . . Not enough space, and a little congestion to the time line, difficulty in keeping up with things. It's a lot slower getting things done up here than you realize when you're down there in one-g. . . . In some respects, it's easier because weighty things are easier to move around, but, on the other hand, everything just tends to take off if you let go of it. . . . it's been a great experience. I don't think there's any way anybody can express how beautiful it is up here.

Looking to the future, Leonov was convinced that mankind was just at "the beginning of a great journey into outer space." As with the other ASTP crewmen, he hoped to have a chance to fly again. Stafford agreed and said that he would like to fly on one of the early Shuttle missions. "And I would hope that if Alexey would have a vehicle developed by [his] country that we could fly . . . in a joint mission." Not to be outdone, Leonov added, "I would always like to fly with friends . . . whom one trusts and with whom it is not dull to work. . . ."36

The crews returned to other items on their flight plan. Slayton, as part of the earth observation experiment (MA-136), took photos of ocean currents off the Yucatan Peninsula and in the Florida straits. He also tried to observe the red tide phenomena - marine micro-organisms that cause the water to appear red - off the coast of Tampa and in the vicinity of Cape Cod. But this visual exercise was not completed because of cloud cover. Brand's travelogue of the East Coast of the U.S. was likewise hindered by the clouds, but he gave the narration anyway, describing the climate and flora of Florida, North Carolina, Virginia, Washington, the Middle Atlantic states, and New England. As the ships passed over Massachusetts, Brand noted that Robert H. Goddard had launched the world's first liquid fueled rocket from that state on 16 March 1926.37

Leonov narrated the events of the fourth transfer as he saw them. He stressed the large amount of work they had to accomplish during the joint phase of the mission, including five bilateral experiments. Although this "saturated program" seemed at times to be more than the five men could handle, they managed to complete all their tasks. Slayton, Brand, and Kubasov assembled the two halves of a medallion commemorating the flight, and then they exchanged tree seeds. As Slayton juggled television equipment, [339] Stafford and Leonov bid their final farewell. All these exercises climaxed one of the most complex television scenarios ever conceived and executed.

Tom Stafford shook hands with Leonov and Kubasov, bidding them farewell at about 3:49 in the afternoon. He then moved back into the docking module, and the space men closed the hatches for the last time at 4:00. Once the checklist for securing the hatches and executing the pressure integrity check of the seals was completed, the crews set about routine housekeeping chores - stowing equipment and making certain that all was in readiness for their next meal. For the statistically minded, the records indicate that Stafford spent 7 hours, 10 minutes aboard Soyuz, Brand 6:30, and Slayton 1:35. Leonov was on the American side for 5 hours, 43 minutes, while Kubasov spent 4:57 in the command and docking modules. To those at work in space and on the ground, it seemed longer.

Before finishing all the items on their pre-sleep checklist, the Americans paused to listen to the news and sports as read by CapCom Truly. Included in his report was mention of an American home exhibit that had just opened to enthusiastic crowds in Moscow. Called "Technology in the American Home," the display was designed to give Soviet citizens an idea of the gadgetry available to the American homemaker. While no one commented on the fact, it was just such an exhibit that had sparked the Nixon-Khrushchev debate in 1959. In 16 years' time, the international scene seemed to have changed dramatically.

Although the crew signed off for the evening on schedule at 7:20, they spent an uneasy first few hours. In addition to being very tired from the activities of their fourth day in space, they were jangled awake an hour later by a master alarm that reported a reduction in docking module oxygen pressure. This problem was no real hazard, and it was quickly solved by an increased flow of oxygen into the DM, but it kept the crew from getting all the sleep for which they had been scheduled. When wake-up time came at 3:13 on the morning of the 19th, the crew failed to hear the musical strains of "Tenderness" as sung by the Soviet female artist Maya Kristalinskaya, with which the ground team had hoped to gently waken them. But 15 minutes later, they were awake and ready to begin their fifth day. Next door, beyond hatches three and four, Leonov and Kubasov were getting prepared, too.

33. [NASA News Release], Apollo News Center, JSC, "Change-of-Shift Debriefing #10," 18 July 1975.

34. Program Operations Office, "ASTP Technical Air-to-Ground Voice Transcription," pp. 340-355; Hal Piper, "Moscow Shops Filled for Space Launchings," Baltimore Sun, 16 July 1975; Bill Anderson, "Its Just Another (yawn) Space Flight," Chicago Tribune, 17 July 1975; Gregg Kilday, "Hyping the Space Show," Los Angeles Times, 17 July 1975; "Millions Watch Awestruck; Soviet Leaders Hail Mission," Christian Science Monitor, 22 July 1975; and Lee Whinfrey, "Platitudes Dull in Space, Too," Philadelphia Inquirer, 22 July 1975.

35. Program Operations Office, "ASTP Technical Air-to-Ground Voice Transcription," pp. 364-367.

36. Ibid., pp. 405-415; Thomas O'Toole, "Apollo Soyuz Crews Make Final Visit," Washington Post, 19 July 1975; Albert Sehlstedt, Jr., "Space Visit Ends," Baltimore Sun, 19 July 1975; and Peter Reich and James Pearre, "Apollo, Soyuz Crews End First Space Visit," Chicago Tribune, 19 July 1975.

37. Program Operations

Office, "ASTP Technical Air-to-Ground Voice Transcription," pp.

419-420.

Next