After Apollo: What?

As the Soviets recovered from their tragedy and evaluated their manned space flight plans, NASA continued its preparations for Apollo 15. The agency's leadership was also looking with uncertainty to the future of its man-in-space efforts. Prior to his departure from NASA the previous autumn, Tom Paine had announced a reshuffling of the remaining Apollo missions. In a press conference on 2 September 1970, the Administrator had discussed these decisions, which reflected a husbanding of NASA's dwindling share of the national budget. The agency wanted to accomplish many goals, but these had to be attained with a limited number of dollars. As the 1969 Space Task Group studies had suggested, NASA would have to balance its present wants against future budgets. A shifting of current project monies would have to take place if NASA wanted not to jeopardize its plans for the future.64

Paine and his colleagues realized that during the 1980s there would be no manned missions to Mars, no other bold ventures equivalent to the lunar goal of the 1960s. Paine said that the principal decision facing the agency was "how best to carry out the Apollo and other existing programs to realize the maximum benefits . . . while preserving adequate resources for the future." [152] NASA had decided to concentrate its manned efforts on three earth-orbit programs - Skylab in 1973 and Space Shuttle and Space Station in the 1980s. The earth-oriented unmanned program would include early development of the Earth Resources Technology Satellites and the Applications Technology Satellites. An unmanned planetary program would involve the Grand Tour flights to distant planets, the Viking Mars orbiters and landers, and the Pioneer missions to Venus, Mercury, and Jupiter. Add "a healthy aeronautical research program" to that list, and the demands on a shrinking budget were obvious.

One immediate way to conserve money was to reduce the number of Apollo moon landings. To pare $42.1 million from the fiscal year 1971 budget, two missions were canceled, and manpower levels at the manned space centers were scaled down accordingly. These decisions were taken not only reluctantly, but also against the advice of scientific agencies external to NASA. Apollo's remaining missions were redesignated 14 through 17, and the so-called "residual" hardware would be made available for Skylab, Space Station, and other programs that might follow the final lunar landing in 1972.

With astronauts Alan B. Shepard, Stuart A. Roosa, and Edgar D. Mitchell aboard, Apollo 14 conducted a successful lunar exploratory trip in 1971. The 31 January-9 February mission was slightly marred by the failure of the probe assembly to operate smoothly as Commander Shepard tried to dock the CSM with the LM. Shepard and Mitchell spent their 9 hours and 24 minutes on the lunar surface exploring the terrain, but NASA hoped to increase considerably time spent on the moon during the next flight.65

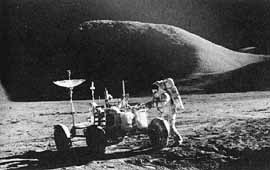

Apollo 15 stressed longer EVA periods and use of the lunar roving vehicle. One hundred hours after a 26 July launch, David R. Scott and James B. Irwin separated their lunar module Falcon from the CSM Endeavour piloted by Alfred M. Worden and headed for a touchdown in the mountainous Hadley-Appenine region near Salyut Crater. The results of their exploratory work were excellent, and Scott and Irwin set several records in the process. They had spent over 63 hours on the moon's surface, conducted a total of 18 hours and 35 minutes in extravehicular activity and traveled 28 kilometers in their moon buggy. But for all its success, Apollo 15 did not bring much joy to the NASA people in Washington, Houston, and Huntsville, for only two more lunar missions remained.66

When James Chipman Fletcher was sworn in as the fourth Administrator of NASA on 27 April 1971, he became the head of an agency that was entering a new era. Fletcher, a physicist by professional training and a university president during the turbulent 1960s, had a personal background in the aerospace world and understood some of the problems that NASA....

[153]

Apollo 15 astronaut James Irwin, on the moon, unloads equipment from the lunar rover. This photo, in which Mt. Hadley looms against the horizon, was taken by David Scott. August 1971.

....would be facing in the years ahead. Reflecting the spirit of both the adventurer and the realist, he commented to the press after the announcement of his appointment that an important goal faced the agency - "to achieve . . . balance between manned and unmanned programs. It would be very exciting for man to go beyond the moon but that . . . is a little beyond the nation's budget right now." Such a statement might at first appear to have been somewhat flippant, but it could be taken as a manner of saying to the NASA team, "Do not despair; there is still important and exciting work to be done."67

Dr. Fletcher also announced very early that he supported closer cooperation with the Soviets. On 10 March, during a one-hour hearing before the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Fletcher told the Committee that the U.S. had made "some small steps" toward cooperation with the U.S.S.R.; now "we can make even larger steps." But the possibility of reducing the long hiatus between the Skylab missions in 1974 and the first Shuttle flights in the 1980s was another reason why Fletcher was interested in talks about a joint mission with the Soviets.68

At a pre-launch press briefing for Apollo 15, Dale Myers, Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight, had spoken about the post-Skylab studies under way. He pointed out that there would be four Apollo CSM's left over, three from the canceled moon flights and one that had been set aside as a backup for Skylab. Studies conducted in Houston indicated that these spacecraft could be flown in earth-orbital missions for about $75 to $150 million each. One possible use for these CSMs would be to launch one a year, beginning in 1975, for earth resources surveying missions lasting from 16 to 30 days each. Of these four spacecraft, one could be set aside for a rendezvous and docking mission with the Soviets. Still another possibility would be orbiting a second Skylab, using the backup CSM for the flight [154] planned for 1973, but that would be very expensive and would require developing new mission goals for Skylab B.69

An interim manned program of some kind was highly desirable. In the first place, it would permit NASA to hold together its launch and flight control teams. Keeping these people together was as much a question of morale as it was money. The men working at Houston and Cape Canaveral were action-oriented; they needed the challenge of actual flights. And second, the crewmembers who trained for the last Apollo flights would still be eligible to fly in the Shuttle period, but they too might grow restless and disinterested if there were a four- or five-year break in flights. Availability of funds would determine the feasibility of an interim project for the space agency.

Myers said that there would probably not be money enough for both a full-scale Shuttle program and interim Apollo flights. If NASA decided to develop the Shuttle booster and orbital stages simultaneously, then there was little likelihood of any flights between the last Skylab visit and the first Shuttle launch. He pointed out, however, that a second approach might be taken. NASA could develop the Shuttle orbital spacecraft first, and while glide tests were being conducted with the early prototypes continue development on the reusable launch boosters. Under such a "phased approach," it might be possible to finance some other missions. But the key guideline was to undertake only those efforts that could be carried out without draining resources from the major effort - Shuttle.70

64. NASA News Release [unnumbered], "FY 1971 Interim Operating Plan News Conference," 2 Sept. 1970; and "New Yew Prospects Glum in Aerospace Industry," San Diego Union, 3 Jan. 1971.

65. NASA, MSC, "Apollo 14 Mission Report" MSC-04112, May 1971; and NASA, MSC, "Apollo 14 Mission Anomaly Report No. 1; Failure to Achieve Docking Probe Capture Latch Engagement," MSC-05101, Oct. 1971.

66. Ronald Kotulak, "Manned Moon Flight Program Nears End," Chicago Tribune, 14 Feb. 1971; NASA, MSC, "Apollo 15 Mission Report," MSC-05161, Dec. 1971; "America's Future in Space," Washington Post, 16 Aug. 1971; Walter Sullivan, "Apollo 15: New Clues from the Men on the Moon," New York Times, 8 Aug. 1971; and Thomas O'Toole, "Our Surprising Moon," Washington Post, 8 Aug. 1971.

67. "New Director of Space Agency: James Chipman Fletcher," New York Times, 2 Mar. 1971.

68. Thomas O'Toole, "NASA Nominee Favors Cooperation with Russia" Washington Post, 11 Mar. 1971; and U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences, Nomination of Dr. James C. Fletcher to be Administrator of National Aeronautics and Space Administration, 92nd Cong., 1st sess., 1971, p. 14.

69. John Noble Wilford, "U.S., Soviet Weigh Space Linkup," New York Times, 18 July 1971; NASA, MSC, "Post Skylab Mission: Summary Report," 17 Mar. 1971 (enclosure to letter, Gilruth to Myers, 25 Mar. 1971); Maxime A. Faget to distribution, memo, "Post-Skylab Mission Study," 30 Apr. 1971; Berglund to distribution, memo, "Post-Skylab Mission Study," 14 May 1971; Gilruth to Myers, 25 Aug. 1971; NASA News Release Apollo 15 PC22, "Space Shuttle Briefing, Kennedy Space Center," 24 July 1971; and interview, Christopher C. Kraft-Ezell, 29 Mar. 1976.

70. John Noble Wilford,

"U.S., Soviet Weigh Space Linkup," New

York Times, 18 July 1971; and

interview, Kraft-Ezell, 29 Mar. 1976.

Next